Ethical Issues

Kindness is the golden chain

by which society is bound together.

Goethe

What are ethics and why bother with them?

What are ethics and why bother with them?

A university student is anxious about his upcoming biology exam. Though he’s studied all term, the course material has been hard to understand. He has four other finals to prepare for, and the workload feels overwhelming. When he gets a text from a friend offering a swiped copy of the test, the student is grateful to have less work to do and less anxiety about the bio final.

A man driving home from his work at a warehouse, tired from a long day of stacking boxes and following orders, sees a woman on the side of the road standing beside a car with smoke pouring up from the engine. In spite of his own eagerness to get home to dinner and an easy chair, the man pulls over and helps her.

A young woman is celebrating her recent promotion at work with co-workers. As they crowd into their favourite restaurant, she’s thinking of ordering her usual saag paneer and naan. But she hesitates as her colleague speaks up, saying, “I know you’re a vegetarian, but, honestly, I don’t really understand why. After all, animals are going to die whether or not we kill them for food. And how do you know plants don’t feel pain, too? Besides, meat tastes so good! I’m ordering the chicken. Why don’t you try some, too?” The young woman hesitates, unsure what to do or how to answer the questions. She’d like to fit in, and perhaps experimenting with different things, like eating meat, is part of what being young is about.

How do we want to be in life? How do we want to connect to other people, to animals, the environment, our work, our play, our spiritual lives, ourselves? The answers to these questions centre around our ethics and can be complicated. Ethics refers both to a field of philosophical study and to practical guiding principles that help determine what is right and good in the world. They can be a moral code, or an effort to lead a life of integrity that may or may not be rooted in religion. People face ethical decisions every day regarding how we treat others, how honest we are, what and whom we vote for, how we work at our jobs or run our businesses or raise our children, choose our food, make decisions about our health, or a multitude of other possibilities that create the framework of our lives.

Being ethical is about being a good human. Being ethical is not about just following laws or traditions. We can all easily think of laws and traditions that have been, or are, unethical: legalized slavery; laws that discriminate against a particular race, religion, gender, or sexual orientation; traditions that keep women from being educated, that grant respect and power only to some castes or social groups. Each time and place has its own struggles with creating an ethical society, just as the individuals in that society struggle to embody their personal ethics.

Being ethical is about being a good human.

Finding an ethical code that rings true is a huge task for each individual, and one that each person can only accomplish for him or herself. We’re all influenced by our family, peers, religion, schooling, society, and by the times in which we live, but ultimately most of us want to set a course for ourselves. As we experience life – as we get an education, care for family and neighbours, travel, see the beauty and the suffering of the world, or find partners – we figure out our own ethics. Often we begin to think beyond just our own families and homes, to feel empathy for people we’ll never meet and concern for places we’ll never go. We expand our ‘circle of compassion’. Our ethics both spring from, and create, our experiences.

Some people turn to religion for an ethical code; some turn away from religion for the same thing. Each of the major religions of the world has devised guidelines or commandments that share similar basic ideas – treating others the way we want to be treated; taking care of our children and our parents; honouring life; being honest, loving, and compassionate.

Let’s think about the ideal that human life is to be respected and preserved, that taking another’s life is not the rightful decision of any individual. Interpretations of this belief vary. Applying this simple, basic principle to the realities of life can be complex, resulting in difficult decisions. Sometimes families decide to remove life support from someone they love dearly because that person is lingering in a vegetative state. Many people who oppose a woman’s right to choose an abortion would grant that right in cases of rape. Others believe that an incurable disease is justification for a person to take his or her own life. Religious or spiritual beliefs that vary in many other ways often agree that killing in self-defence or in defence of another, if absolutely unavoidable, is ethical. So even in our efforts to preserve human life, we find situations that are not straightforward.

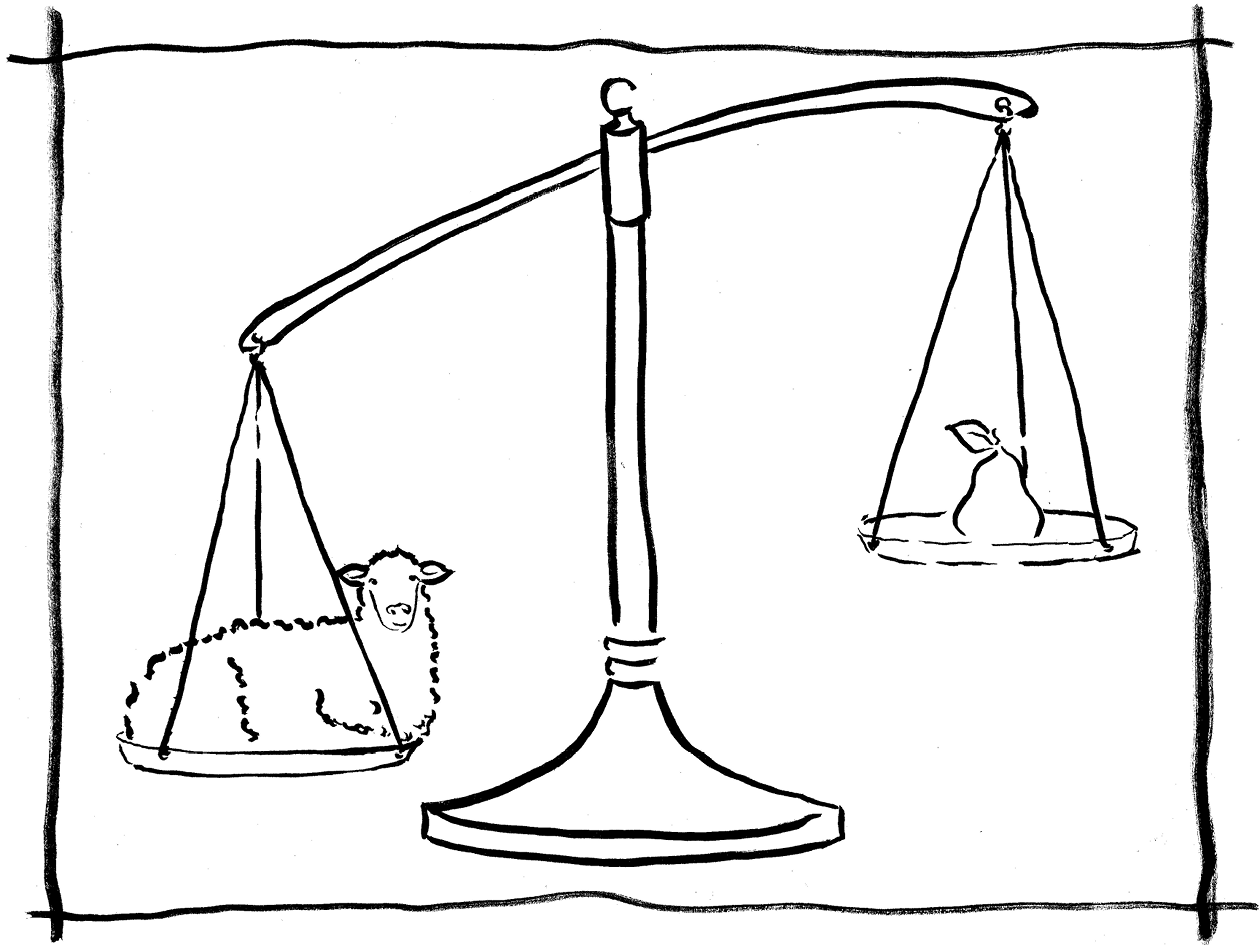

When we begin to consider plants, birds, fish, and animals, matters become increasingly complex. Some people think “do not kill” refers only to humans and not to any others who are part of the teeming life on our planet. Though such a rationale is seriously flawed from the point of view of a vegetarian, it is understandable. After all, any version of “do not kill” is impossible to follow completely, as every creature must consume some form of living matter to survive. However, all societies acknowledge differences between killing humans, animals, insects, and plants and between killing for pleasure and for necessity. The few examples of people who have killed and eaten humans for sport or pleasure are generally considered barbaric. Yet in every nation, eating animals is common practice, mostly considered normal and good among much of the population. Many, many people do not consider killing and consuming animals to be an ethical issue at all. As we move down the food chain – humans, mammals, fish and fowl, insects and reptiles, and plants – the acceptance of killing becomes more common. We seem to recognize that a hierarchy of consciousness and value exists, with humans at the top and plants at the bottom.

Much of the world’s population eats a wide variety of four-legged animals. Sheep, goats, cattle, pigs, squirrels, bear, deer, rabbits, guinea pigs, elephants, rats, horses, monkeys, dogs – scarcely any species is exempt from becoming food. Ironically, most of these mammals that humans eat flourish on largely vegetarian diets.

Eating fish of all types and birds of all kinds is more common than eating mammals. Where people can afford to make a choice, some refuse to eat ‘red meat’ – attributing a higher level of consciousness to these animals – yet willingly eat all kinds of fish and birds. Using insects as food is also ordinary for some people, if repellent to others. Of course, everyone eats plants.

So we all kill to eat. However, virtually none of us murders our own species in order to eat. Such an act is considered horrific, yet killing other species is not only accepted, but often applauded. While human life is universally seen as valuable, animal life is seen as expendable.

Can we expand our ethical standards beyond who or what matters just to us?

Can we expand our ethical ideas about the importance of life to include animals? In a way, many people have – most would never consider eating their pets. Birds, cats, dogs, horses, gerbils, lizards, turtles, and other animals are eaten in some cultures while valued as companions in others. The puzzling thing is that so many people who lavish love and money on their own animals, who wouldn’t dream of using them for food, don’t question the killing and eating of other creatures. Just as people we don’t love or even know still have worth, so, too, do animals.

Can we expand our ethical standards beyond who or what matters just to us? It’s easy to love an animal – to scratch a puppy’s belly or groom a horse. We get so much from our relationships with our own pets. Surely we can understand that creatures we may never encounter also have an equal value and deserve to live. Virtually everyone enjoys watching birds soar, or monkeys swing gracefully from branch to branch. Tourists travel from every part of the globe to see the majestic big cats of the Serengeti Plains, the howler monkeys of Costa Rica or the migratory whales of the Pacific Ocean. Every animal is unique, and many have emotions we can easily observe if we are prepared to look. Understanding the intrinsic worth of all animals – not simply the ones we know personally – is an important step in our ethical/spiritual maturity and has reverberations across our lives and into the world we inhabit.

Life and death in a factory farm and slaughterhouse

Life and death in a factory farm and slaughterhouse

Let’s return to farms, sources of most of the world’s meat. Today, the idyllic vision of gently nurtured, contented, healthy creatures ambling through barnyards and munching on verdant grasses is mostly a myth. Modern factory farms are an environmental threat, spewing toxins and animal waste into our earth, air, and water. Now let’s look at the lives of farmed animals through the lens of ethics.

One of the difficulties here is that conditions for keeping and killing animals vary from nation to nation, from farm to farm, and even from slaughterhouse to slaughterhouse. Some places have more humane practices than others, but in all these places the animals end up dead, even if the suffering they experience while living and dying varies from humane to hideous. The worst conditions exist on factory farms, where chickens, turkeys, pigs, or cattle lead lives of misery until their often brutal deaths.

On dairy farms, calves are separated from their mothers within a few hours of birth. Many males are taken to be raised for beef. Other males and excess females – ones not needed for milk production – are confined in small veal cages two feet wide, with heads chained to restrict movement so the calves can’t walk, turn around, or even lie down comfortably. Thus, they can’t develop muscles, so their meat is very tender and considered a ‘delicacy’. Veal lovers like their meat pale and anaemic, so the calves are fed synthetic formula, not their mother’s milk. In addition to the physical pain, the calves and their mothers are deprived of the emotional bonding that is normal for cows.121 Cows are social animals with long memories and strong family bonds. ‘Strong family bonds’ are not economically feasible on most dairy farms. Calves are often taken away from their mothers within twelve hours so that the mother’s milk can be used by humans rather than calves. While cows naturally live 20–25 years, dairy cows confined to milking stations and subjected to constant artificial insemination and pregnancies are worn out in four or five.122 Then they’re shipped off to make low-grade meat products.

The situation for chickens, ducks, and turkeys is arguably even worse. In the average factory farm shed, tens of thousands of fowl are crammed without room to spread their wings. Because the space allotted for each animal is tiny, they can scarcely move at all. These sheds reek with a stench of ammonia from bird droppings that burns eyes and lungs and can cause blindness. Workers wear gas masks while the fowl get chronic respiratory diseases, sores, and blisters.123 Under this stress, birds may begin feather-pecking, so their beaks, filled with nerve endings, are “sheared off with a hot blade.”124

The plight of caged, egg-laying birds is similar, with the additional misery of spending their lives in metal ‘battery cages’, with four or five chickens crammed into a tiny space. Because they’re constantly rubbing against and standing on metal wire, the birds suffer feather loss, bruises, and damage to their feet – feet meant to scratch earth. Artificial lighting extends the hours of ‘daylight’, which increases egg production. However, the unnaturally high rate of laying eggs leaches calcium from bones, causing painful osteoporosis.125 When egg production declines, the fowl are sent for slaughter. In the United States, they are exempt from the Humane Slaughter Act, which decrees that animals should not die in pain.126

‘Cage-free’ and ‘free range’ eggs are hot topics these days as educated shoppers discover the conditions of animals in factory farms. Understandably, many people want to avoid responsibility for cruelty by eating eggs from happy chickens. Unfortunately, ‘cage free’ means only that – the metal bars aren’t around a chicken’s body. It doesn’t mean that the hen has any more space than a caged hen or avoids debeaking or lives in a shed where the lights go off at night. Similarly, ‘free range’ doesn’t mean ranging freely. All it means is the animal must have access to a small area – perhaps just five square feet – of outdoor space. Whether the hen ever gets to it is not considered. With tens of thousands of hens in a shed having perhaps one small door to one tiny outside plot, we can see how the designation ‘free range’ means virtually nothing.

Most people remain largely ignorant of what life is like for the farmed animals we eat. While the torture of veal calves has been relatively well publicized, much less is known about hens reared for egg production, and the sad fate of male chickens is commonly overlooked. Reading the details of how animals are killed is gruesome. Many people simply choose not to know. However, perhaps understanding the reality of suffering for other beings is a way to expand our circle of compassion.

Male chicks in the egg production industry, who can’t lay eggs and are not suitable for meat – because they haven’t been genetically manipulated to have large breasts and thighs – are put through meat grinders while still alive, suffocated in trash cans, or gassed.127

Meanwhile, whole fowl destined for dinner plates, on entering a slaughterhouse are pulled from crates and shackled upside down by their ankles on a moving belt – a process that often causes broken bones, bruising, or haemorrhaging. They move along to an electrified water bath, and when their heads are dipped into the water an electric current runs through their bodies up to the metal shackles, hopefully stunning the birds, before they reach a mechanical neck cutter.128 The Humane Society of the United States reports that, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, “millions miss the blades and drown in tanks of scalding water while conscious and able to feel pain.”129

An alternative method used to kill fowl is gassing the birds while they are still in transport crates. Some researchers say this method of killing is more humane than electrical stunning, as the fowl are never handled or shackled while alive and are not conscious when their throats are cut.130

Larger animals may be strung up on a factory production line to be slaughtered in large groups, or killed individually in the backyard of a farmhouse. They may be zapped first with a stun gun or left fully conscious to feel the slicing of a knife. Pigs may be knocked unconscious with a bolt gun, strung up conscious from a tree branch or hung from a hind leg, stabbed and allowed to bleed out, disemboweled, and split in half with a bone saw. All kinds of creatures die all kinds of deaths to feed humans.

When we eat their meat, we have participated in their deaths. How can we do this to another being? How can we do this and create peaceful, joyous lives for ourselves? Sooner or later, we all face the consequences of our choices. In the studies of both science and spirituality, we learn that “every action has an equal and opposite reaction.”131 Whether we think of this as a scientific law, a spiritual teaching, or simply folk wisdom, the concept is the same. “We reap what we sow.” “What goes around comes around.” Eastern spirituality refers to the same idea using the term ‘karma’. At times, the results of our actions and choices are obvious and immediate; at other times, they’re obscure or delayed. Nevertheless, wait for it ... here it comes. Actions create reactions, whether or not we’re aware of the connections.

Believing that actions have results offers a practical way to understand what we see happening daily, even if the results aren’t immediately apparent. Dumping nitrates into a stream doesn’t instantly cause dead zones in our oceans or create health risks for infants, but continued dumping over time causes severe environmental and health problems. Our actions and choices – even our choice not to take action – sooner or later have consequences.

Many spiritual teachers have explained that the consequences of our actions can ride with us from lifetime to lifetime and manifest in ways we cannot predict. We can grasp how physical science works, but we often lack the ability to see how spiritual science works. If our actions include consuming dead animals for the taste, what are the reactions to such consumption? Remembering that “every action has an equal and opposite reaction” can influence our choices. Our behaviour may continue to change if we add the belief that, while the reaction may not happen in this lifetime, it will eventually happen. Perhaps then we pause before tearing into that beef patty or adding chunks of lamb to our curry. What will be the reaction to such an action? How can such food choices lead to the deep sense of wellbeing every human craves?

Both because we care about other creatures and because we care about ourselves, choosing to be vegetarians is a natural, healthy, and compassionate approach to life.