July 2010

King of Kings

Brighter than the noonday sun, Softer than a newborn baby, Cooler than a summer moon, Finer than gossamer silk, Your smile spans the seven skies …

The Battle against Negativity

It is tempting to think that once we have resolved to follow the spiritual path, life will be straightforward from now on …

The Shocking Truth

The Master keeps telling us that this world is not really our true home, but we keep right along planning everything as though we will be here …

The Master’s Discourse

The purpose of the living Master’s discourse is to impress upon us the need to experience the Divine …

The Season of Summer

As we progress from autumn to the harshness of winter, and finally through spring to the warmth of summer, there is hope in our hearts and we look …

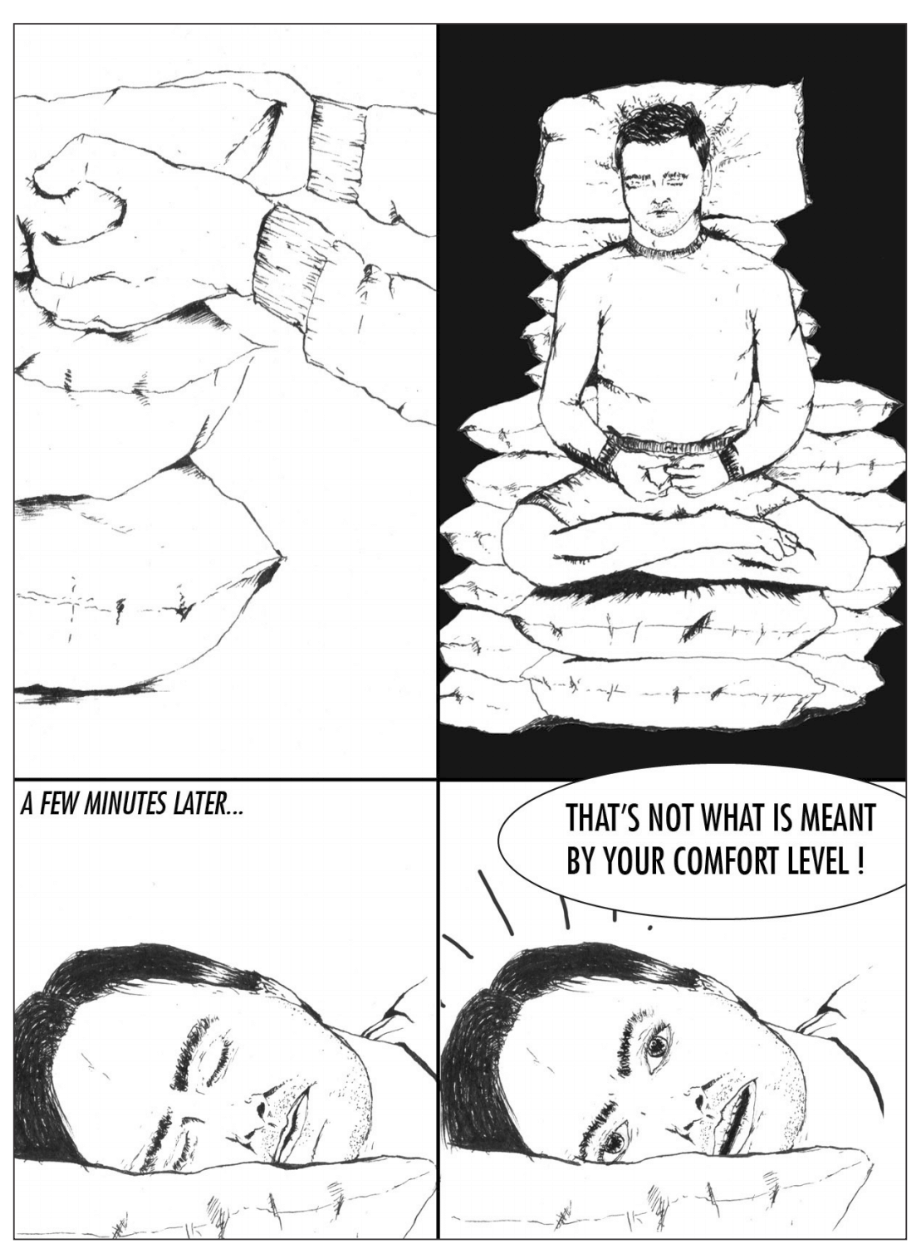

Feeling Funny

…

Reflections on Silence

The invasion of technology in our modern world has contributed to the slow death of silence …

The Seva Talks

The fictional diary of a young sevadar …

Something To Think About

Theory and Practice …

Never Give Up

When we first come to the path, many of us experience a feeling of joy and relief …

Questions and Answers on Meditation

Maharaj Charan Singh answers satsangis’ questions on meditation in Die to Live …

Being between Now and Eternity

As spiritual seekers, one of the goals to which we aspire is the unchanging truth …

Describing the Indescribable

I am bewildered by the magnificence of your beauty and wish to see you with a hundred eyes …

Book Review

Siddhartha …

Start scrolling the issue:

King of Kings

Brighter than the noonday sun,

Softer than a newborn baby,

Cooler than a summer moon,

Finer than gossamer silk,

Your smile spans the seven skies,

Your presence melts into the heavens.

And from that sphinx-like gaze

Pearls of immeasurable knowledge fall,

Into the unfathomed depths of my being.

A loving whisper of unknown knowing caresses me

And return to my ancient home is sealed.

The Battle against Negativity

It is tempting to think that once we have resolved to follow the spiritual path, life will be straightforward from now on. Big mistake. The saints warn that once we have been initiated and start out on the spiritual path, we have identified ourselves as being on the field of battle. The negative, obstructive forces will attack us with greater vigour; although we are assured of final success, we may yet have a tough battle ahead.

We have to turn away from the world whilst living in it in a detached way, and the ruling force of this region will not let us leave without a fight. The world’s temptations and illusions will continue and may intensify, but once initiated we no longer belong to the world. We belong to the Master.

In the world but not of it

If we visit a large aquarium, we look into the tank through a reinforced glass side and see all the marine life within. We are not part of that world, and we could not survive in it. We are merely observers. That is the way we should look at the world at large, as though through a toughened glass window. Clearly, we have to do our duty in the world, but the rest of it can pass us by behind the glass screen, if we practise the art of being an observer rather than a participator. Then we can be in the world but not of the world. Even with events that do affect us personally, we should remember the old Chinese saying, that the wise man observes difficulties but does not experience them.

The present Master has talked about negativity and positive thinking. The world’s media are full of negativity because that sells papers and programmes. We should avoid internalizing any of this negativity or it will harm us.

It is easy to get into the habit of automatic negative and critical thinking, particularly at a low level. Even a small amount of negativity and criticism is very detrimental to our progress. The saints advise us to keep the body active and the mind in simran as much as possible, so that the mind does not slip into its habitual negativity. As the old saying goes, the devil makes work for idle hands. Take life lightly and with a smile; don’t react so much. We need to make choices and decisions using our best judgement and then deal with whatever subsequently transpires.

Worry shows a lack of trust

If we worry, then we are displaying a lack of trust in the Master, who advises us that we have no cause for anxiety about the future. Now that we are safe and secure in the hands of the Master and a bright future is assured, we have every reason to be positive. Whatever our troubles, our situation is but temporary and we are guaranteed a blissful outcome. Why should we be downcast?

Even if we slip, as we will, the Master is positive and always ready to encourage us to get up and get going again. Forgiveness is always there if we take the right attitude. Maharaj Charan Singh once listened to a distraught satsangi confess how he had continued to do so many serious things that were against the Master’s teachings. It was a litany of misdemeanours, and one quite expected the Master to give him a sound telling off at its end. However, Maharaj Ji waited until the satsangi had finished and then merely said, “This is not a very promising start.” He then advised the satsangi to start again that very day, putting the past behind him.

The Master is always understanding, forgiving and positive about what to do next. We continually fall down in one way or another, but that is in the nature of struggle. If we respond to our faults in the right way, if we learn from our errors, if we genuinely seek forgiveness from the Master, then we can readily move on. Equally, that is why the Masters tell us not to criticise others and always be ready to forgive, for that is the way the Master treats us.

The focus of our life should be the immediate goal of reaching the Master within. This entails us being attentive and assiduous in both our spiritual and temporal duties, whilst living through our karmas in a cheerful and contented way. Love is the very essence of the Creator and the Master, and our ultimate goal is perfect unity with them in permanent bliss. If this is what we want, and if we want it badly enough, then we should just be happy to struggle – simply do our meditation and leave the rest to the Master.

The Masters have talked about storming the fortress of the mind. To extend the military analogy, in making a ground attack it is sometimes necessary to lay down what is called covering or suppressing fire. This is loosely aimed but continuous fire that is designed to keep the enemies’ heads down to enable one to move forward on the battlefield and press home an attack. Simran during the day at any and every opportunity is like suppressing fire. It keeps the pressure on the mind to stop it from gaining mastery over our thoughts and actions and it conditions the mind for when our main concentrated attack comes, at the time of meditation. Simran can be used both for mind suppression but also for close-quarters combat with the thoughts that come at the time of meditation. Simran is totally portable, always ready for deployment and never runs out of ammunition. Just use it.

The Shocking Truth

The Master keeps telling us that this world is not really our true home, but we keep right along planning everything as though we will be here forever. It is only when we are shocked at the loss of a person near us, or by some natural catastrophe, that we stop to think how very fragile our existence here is. The work of a lifetime can be lost in the blink of an eye. All our hopes can be shattered in a moment. The Master, like a loving parent, keeps whispering in our ear that we should wake up, we cannot stay here, we have an important journey to make. We have to go home.

We would love to get rid of our troubles. But we must first be clear about what direction we should take, and then act on our decision. Building up our hopes and attachments in the world is very easy, but it never brings us much peace of mind. Even the best worldly moments quickly turn into frustration and dissatisfaction. Shabd and Nam are the only reality that can give us peace and strength. But sometimes it takes big shocks in the world to make us realize this.

The Master’s mission is to uproot us from this world. But think how lovingly he administers even the rude shocks of life. Is there not always a sense of his caring presence when we undergo real difficulties? The Great Master said that when a child has a fever he may ask for sweets, but because his mother cannot bear to see him suffer anymore she would instead give him bitter quinine for his fever. The Master too cannot bear to see us suffer anymore. We have been wandering too long, exhausted and dispirited in this world. He is definitely helping us. He is very actively uprooting us, leading us out of this half-life into a place where we can really experience love and joy.

The Master has committed himself to take us home: we just have to keep waking ourselves up to this reality. The journey, which will surely be the most exciting adventure we have ever experienced, has already begun. We are like travellers who leave home before dawn and so cannot see the progress they are making through the unlit streets. We can at first barely sense that we are moving. But as the dawn inevitably comes, we see – faintly at first, then more clearly and beautifully – the landscape moving past us. The Master wields the power of the Creator. His love is the most powerful force in existence. It is directed to each of us individually. Like a powerful sun shining on tiny dewdrops, how can we avoid dissolving and rising upwards under his influence?

Urging us inwards

Everything seems so important to us in this world, and it is a terrible struggle to turn our attention inwards towards that inner light, which we cannot yet see brightly enough for it to exert a constant attraction. But the Master is always urging us inwards. The shocks and troubles of this world are a powerful cure for our inertia: they help to dissolve our sense of security in a world of worthless, shifting values. We should use these moments to reassess our link to the Master, try to put our lives into perspective, and put our emphasis where it should be – on spiritual wealth and security, rather than on worldly things that are bound to let us down in the end.

Even if events seem hard and cruel, we can always find a little inner strength with which to face things. Sometimes our worldly losses actually come as something of a relief. The value we place on the people and things around us in this world often just creates stress in us. We are in truth yearning to be free, and when things go badly it can sometimes help us to get a sense of that freedom. It is an opportunity to practise the spiritual approach to life, to accept a simpler lifestyle and to return to the natural desire for the Lord. It is the breaking of another of the chains that bind us.

The Master pours such love on us, even when we are being quite indifferent to him. He has the wonderful ability to love even the most hardened heart. He is always ready to embrace us, even when we have just been behaving in a manner far from spiritual. It is our awakening that he desires: to see us look to him for help and comfort rather than looking to this dreadful world, which has done nothing but tempt and trouble us for so many ages. When our faces look up towards the Master, those tears of ours are sweet to him. He brushes them away without a thought and fills us with a measure of his own love. Each step, each interaction with the Master builds a little more strength, a little more love in our hearts. It opens up the window of light and makes the show of the world appear that much paler by comparison.

Why prolong the agony?

Definitely we should be trying to struggle to get out of this mess we are in. Why prolong the agony? We should make a real effort to help the Master help us out of here. Every move the Master makes is love, pure love, awakening us from the limitation of our dreams. We have to learn the steps to the Master’s dance. But surely it will come easily in the end, because every step we take towards the Master brings us closer and closer in harmony with him.

We will definitely arrive at that state of loving acceptance, which is real freedom from our cares. It is just that today, and every day, we should try as hard as we can to do things with him in mind. Put him first. Be as courageous as we can. Forget our troubles and be thankful that we have such a wonderful friend working on our behalf. After all, how long are we going to be staying here? Something wonderful has already begun.

The Master’s Discourse

The purpose of the living Master’s discourse is to impress upon us the need to experience the Divine. This purpose, if pursued with sincerity and unwavering determination, takes on such momentous proportions that it radically changes our direction in life. However, our life experience shows that the ruthless enemy within, our mind, has often thwarted most of our intentions, no matter how noble. It is not possible to persuade the mind, through reason alone, to change its ways. The practice of Surat Shabd Yoga is the sure way to convince the mind that its determined resistance to noble ideals has brought it no tangible benefits or peace. Over an inestimable period of time and through various life experiences, the mind has always acted in its own short-term interest. That is largely why our attention remains fragmented and fickle. Baba Ji has often mentioned that we are simply reacting to the events of life rather than having a clearly defined objective.

The goal of God-realization is the highest of pursuits in human life. Because we are created in the image of God, our souls long to merge back into the divine source. Since the Supreme Lord resides within the human body, we will succeed in our objective if we adopt the internal form of devotion, as instructed by the Saints.

The Lord, though residing within the human body, cannot be perceived by the mind and the senses. To develop the spiritual faculty, the traveller on this path stands in need of constant guidance and help from the living Master. Would it be a wise move to scale a mountain without preparation and without a guide? To reach the Himalayan peaks, the mountaineers have to consider the challenges that have to be overcome if they want to succeed. It takes careful and prudent planning, close study of the suitable routes to the peak and consideration of the severity of the incline as well as the inclement weather. They have to go through an intensive course of mental and physical fitness. In addition they have to travel light lest excessive weight robs them of the objective they seek.

Our spiritual challenge is no less than a mountain climb, for the Lord resides in the highest mansion. For this great journey, how prepared and committed are we? To change the analogy, we want to travel by Sach Khand Airline to the highest stage, yet we turn up with our oversized and over-laden suitcases. Though the travel is free of charge, the condition of travel stipulates that the passengers are allowed no luggage in the hold, no hand luggage and not even a small bag or a purse! If we don’t feel ready to part with our suitcases, our worldly attachments and belongings, the question of undertaking such a journey is no more than a dream.

The spiritual Masters, in their extreme kindness, encourage us to come on board, and offer us the inducement of the priceless gift of the Shabd. The only way to appreciate this gift is through our daily meditation and constant remembrance of the Lord. In the meditation process when the mind is rubbed against the Shabd, it acquires a certain level of purity that enhances its power of discrimination and the ability to make sound judgements on worldly and spiritual issues. For the first time the mind senses the illusory nature of the world and begins to detach itself. Maharaj Charan Singh used to mention that detachment is only possible as a result of attachment to the Shabd. This is a permanent outcome, a natural consequence of experiencing the sweetness and glory of the Shabd within. The mind, now having seen the error of its ways, is content to shed worldly baggage and ride the vehicle of Shabd to rest and be at peace. Our soul, when extricated from the mind, has no baggage anyway, being pure in essence. Having regained its pristine purity, no insurmountable obstacles remain to prevent the soul from merging in the Divine.

The Season of Summer

As we progress from autumn to the harshness of winter, and finally through spring to the warmth of summer, there is hope in our hearts and we look forward to the season of bounty. Summer for us represents such a season, when nature displays its beauty both in the wild and in heavily scented, colourful gardens; the fields bring forth crops for our sustenance and the trees yield delicious fruit and provide shade. The sun shines brightly, and for a little while our minds are lifted from our preoccupations.

In nature these seasons have a purpose, each following the one before in nature’s self-perpetuating cycle. We, as inhabitants of this land, under the same sun and sky as the rest of nature’s creatures, are not immune to these changes, to which we also must adjust. Maharaj Charan Singh often explained that the winter has to come and the summer has to come, but if we don’t adjust to the variety of the seasons then we will end up suffering all the more.

Our karmic seasons

However, our karmic seasons are as erratic as they are unpredictable. Virtually in a day we could experience the withering of our expectations as in autumn, the wintry chill of fear over some loss, the hope for recovery as in spring, and the summer flowering of our fulfilled wishes. Enduring such daily fluctuation and uncertainty causes us constant worry, a sense of deep unhappiness. We all wish to rise above this level of total uncertainty. We all yearn for peace and permanent happiness, the end goal for which human life has been granted to us by the Lord.

The saints, during their discourses, explain to us at length the reasons for the daily changes in our fortunes, and also offer a permanent solution towards which we can work each day, in parallel with our other activities. They explain that behind the curtain of the mind there are other worlds of existence or levels of consciousness, which are infinitely superior to this world and where the sense of happiness that can be achieved is beyond our comprehension. The saints go so far as to say that, just as there is no real happiness in this world, equally there is no hint of pain, worry or sorrow in the higher planes of consciousness.

A spiritual guide

For realization of this spiritual potential, on a practical and pragmatic level we must acknowledge that we need the help of a guide in the same manner that we would seek a competent person to obtain a worldly skill useful for our day-to-day living. In the field of spiritual science, the living Master is that unerring and competent guide. The path of spirituality, the sacred science of the soul, is an exact science that is aimed at elevating our essential self, our soul consciousness, to function in the spiritual planes even during our lifetime.

Alongside the practical element of spirituality – our daily meditation – a certain amount of instruction and logical explanation is given for our current state of play and our predicament. The gist of the saints’ teachings is that the soul, our real identity, is trapped here as a result of the adverse actions performed by us under the influence of the lower mind and the senses, which become binding and act as a downward drag on our soul and thus keep it confined to the level of physical phenomena. The saints advise us that if we were to raise our consciousness to the eye centre, riding the vehicle of the sound current already present within us, we would get a foothold in the higher spiritual planes. Once the sound current is grasped, we wake from deep slumber and come alive.

Once the call of the Master awakens the soul, we begin to progress to the place of light, through which we journey back to our eternal home. We can draw great comfort from the fact that the disciple of a Master is not left alone to make his way back home under his own initiative but that he is constantly guided and encouraged to go forward in the loving company of the Master. Mystic literature is emphatic on the point that the Master remains with his disciple every step of the way, until the disciple is delivered safely in the lap of God.

The love of the Master and his overflowing grace are a source of indescribable happiness and engender great strength in weathering the storms of life in relative safety. In the meantime, we must do the best we can in adjusting to the karmic seasonal realities. Those who are under the protection of a living Master, those who accept his words of wisdom sufficiently to mould their way of life so that it reflects the essence of the teachings, are indeed among the most fortunate.

By grace it is possible to have full knowledge of all other created things and their works, and indeed of the works of God himself, and to think clearly about them, but of God himself no one can think. And so I wish to give up everything that I can think, and choose as my love the one thing that I cannot think. For he can well be loved, but he cannot be thought. By love he can be grasped and held, but by thought neither grasped nor held. And therefore, though it may be good at times to think specifically of the kindness and excellence of God, and though this may be a light and a part of contemplation, all the same, in the work of contemplation itself, it must be cast down and covered with a cloud of forgetting.

And you must step above it stoutly but deftly, with a devout and delightful stirring of love, and struggle to pierce that darkness above you; and beat on that thick cloud of unknowing with a sharp dart of longing love, and do not give up, whatever happens.

The Cloud of Unknowing and Other Works, translated by A. C. Spearing

Feeling Funny

When you lose touch with your inner stillness, you lose touch with yourself.

When you lose touch with yourself, you lose yourself in the world.

Eckhart Tolle, Stillness Speaks

Reflections on Silence

The invasion of technology in our modern world has contributed to the slow death of silence. Lying on the sand dunes in the Namib Desert, gazing up at the stars and listening to the roar of the world’s natural sound, provides one form of silence. Going to sleep in a Paris hotel with earplugs and cushions over one’s head achieves another kind of silence. We pay out a lot of money in search of quiet locations in which to de-stress and recuperate from our noisy lives.

Even our homes are not protected from noise: once the telephone used to be in the hallway, then it migrated to the lounge, from there to the bedroom, and now it has become glued to our hand as we have become addicted to and dependent on constant talk, texting and chatter – or, should I say, twitter. Saint Paul writes in the New Testament:

Avoid empty and worldly chatter; those who indulge in it will stray further and further into godless courses …

Bible, 2 Timothy 2:16

We no longer tolerate silence. It is covered by every kind of technical noise: TVs, radios, MP3 players, bass-enhanced stereo sets in cars and at home. We speak of environmental noise pollution: factories grumble into the night sky, motorways are never silent and noisy cities never sleep. Such a cacophony of noise destroys silence and dehumanizes us, as the inner soul since time immemorial is nurtured by interiority, by silent retreat, by the sacred that emerges within when one listens to silence.

Without silence the relationship between the outer and the inner world becomes brittle, and our connection to our interior energy is shattered by the clamour of life. Without inner silence the sacred cannot be heard and the soul cannot be refreshed by contact with it; we cannot be still enough to hear the sound or the song of God. Losing it, we become immersed in the world to which we turn, seeking compensation for this lonely disconnection from God.

It is possible that we deliberately seek out all this noise simply as a way to block out our fear of silence, because silence is so frequently associated with loneliness, lack of contact, or loss of connection and communication. We fear that silence implies a lack of friends, relationships, lovability, connection: we fear the isolation and solitude and the associated pain – things to be avoided at all cost!

Ultimately, silence is equated with the silence of the grave, with death itself. Perhaps, in this way, silence holds humankind’s biggest fear: the fear of death. We see death as the end of relationship, of all comforting chatter, twitter, contact and life itself.

However, this is not the view of the spiritual adepts, who incarnate into this form of existence to show us the way back to the reality of our spiritual identity and relationship with God. Masters past and present tell us that we have to learn “to die while living”. The secret of life lies in our ability to recognize and overcome our fear of the silence of the grave and to rehearse the process of physical death while we are alive – to be released from the fear of it, so that at the time of our actual death we will be able to do what needs to be done.

In the Acts of Thomas, Judas Thomas speaks of his imminent death as something he is looking forward to; there is no fear of the silence of the grave:

… But this which is called death, is not death,

But a setting free from the body;

Wherefore I receive gladly

This setting free from the body,

That I may depart and see him

That is beautiful and full of mercy,

Him that I love, him who is my Beloved:

For I have toiled much in his service,

And have labored for his grace that hath supported me

And which departeth not from me.

Quoted by John Davidson in The Gospel of Jesus

According to the Upanishads there is no death, only a change of worlds – a “setting free from the body”. If this is understood, life is perceived as a continuous flow of divine energy, an eternal consciousness that comes into and out of being. We appear and disappear, we are born and we die in countless forms, throughout the ages, until we are graced by coming into a relationship with a living Master who reveals to us the spiritual reality of the Shabd or sound current and connects us to it.

This sound current, also known as the Word, the Sound, Nam, the audible life stream, or the creative power, is the source of all creation, which manifests itself as sound and light in the spiritual regions. As the soul manifests in the body as consciousness, the Word of God manifests itself as inner spiritual sound. Maharaj Sawan Singh says in Spiritual Gems: “The Supreme Creator and the individual spirit in the creation are connected together through the sound current.”

The Masters show us how to get in touch with the Shabd through a process of self-realization leading to God-realization. The practice of meditation is the vehicle that enables an initiate to begin this journey towards God-realization. Meditation is simply the daily practice of sitting still, for two and a half hours, initially in inner silence, detaching one’s attention from the sense organs to bring the mind to the inner eye centre, where it may concentrate on listening to the Shabd.

Again in Spiritual Gems Maharaj Sawan Singh says: “The soul wants Nam and when it gets it, it pulls up the mind, and the result is peace and joy and freshness.” He further describes this meditative practice, saying:

Stilling the wild mind and withdrawing the attention from the body and concentrating it in the eye focus is a slow affair. A Sufi says: ‘A life period is required to win and hold the Beloved in arms’. Concentrating the attention in the eye focus is like the crawl of an ant on a wall. It climbs to fall and falls to rise and to climb again. With perseverance it succeeds and does not fall again.

Imagine rising in the early morning before the dawn chorus of birdsong, metaphorically camping at the feet of the Master – that is, doing one’s meditation. Gazing into the inner darkness, watching the inner light break through, just as we see the sun rise in the outer world. In this inner, silent world, one senses the consilience between long-forsaken instincts and a growing awareness that there is, within, an autonomous power greater than the mind.

The adepts explain that as the inner light brightens, this awareness develops into an inner vision that mirrors the outer view of the Master. A silent communion unfolds that leads to experiencing the presence of God within oneself. This aspect of meditative practice, say the adepts, leads towards a communion with the Shabd, now experienced as the inner Master, who lies within at the centre of being, sustaining all.

The Shabd, as inner Master, both sustains and is the wholesomeness, the central ordering factor, of our being. It is something to be searched for, to be found and realized. It is also spontaneous and numinous and is able to seize hold of our consciousness and draw us towards it. In the Katha Upanishad it is clearly written:

The pure Self cannot be found through studying the Vedas, nor through learned argument, nor through much hearing of the scriptures. The Self is known only to those It chooses. To them alone It reveals Its true nature.

The Upanishads, Sacred Teachings, translated by Shearer and Russell

The word “Self” here could be seen as referring to the Shabd within. The Shabd is the silent centre and director of our life; it embodies both the aspect of intrinsic being and the aspect of its being known. It has the ability to break through all obstacles to lay claim to a personal life and to connect that life to itself. The fact that the Shabd is the centre and the director of our lives makes it the pivot of a satsangi’s entire existence. The Shabd has the ability to be reflected or meditated on, and in this way it has the ability to be known by the persons who are experiencing and living in and through it. So the Shabd is found both in the subjective and in the objective worlds of a person.

L.R. Puri in Radha Soami Teachings quotes Soami Ji as follows:

O! know thou, Shabd is the beginning of all; and the end of all … Shabd is the cause (of all), and Shabd is the effect. ’Tis Shabd that hath created the whole cosmos.

L.R. Puri further explains:

All things get their power and sustenance from this divine melody or celestial harmony, called Shabd. It is the Life of all lives and the Being of all beings …

The Shabd is thus the Beingness that is both God and the experience of God. We may imagine it as acting as a magnet, gathering and focusing our attention, turning us inwards onto the silent and solitary journey that leads us towards a union with the manifestation of God within ourselves.

When we sit in the initial silence of meditation, camping at the Master’s feet, we become receptive to primordial intuitions of those silent nights in which the stars and fire are one. We remember a mystical union when once we were at one with the creative power. As we camp at the Lord’s feet, waiting as silently as did primordial man in the darkness of his night in reverent awe at the power of the Creator and Creation, we too, in the sacred silence, may open to a connection to the sound of the Shabd and see the light. Even as, over millennia, individuals in their chosen spiritual discipline (whether Buddhist, Hindu, Kabbalist, Muslim, Christian, Sufi or through any other practice) have opened their inner eye to experience the divine presence.

In esoteric mystic teachings, this process takes place through the body, in the interiority of being, yet, in crossing the eye centre, it goes far beyond the body. In meditation, when concentration is achieved, the energies of the body are drawn upwards to the eye centre, known in Christianity as the single eye. To attain this centre, the mind must be disciplined. Maharaj Sawan Singh says in Spiritual Gems: “Spiritual progress primarily depends on the training of the mind.” He instructs the devotee to teach the mind not to be led astray by the senses, nor to allow the senses to form deep attachments to objects, situations, people or circumstances.

The Self is not revealed to anyone whose ways have not changed, whose senses are not still, whose mind is not quietened, whose heart is not at peace.

When the five senses are stilled, and thinking has ceased, when even the intellect does not stir, then, say the wise, one has reached the highest state.

The Upanishads, Sacred Teachings, translated by Shearer and Russell

By overcoming the fear of silence, solitude and darkness and distractions from the inner path, the soul gains the power to attach itself to the Shabd and to pass to the divine regions within. In the Bible (Matthew 6:22), Jesus Christ says, “… if therefore thine eye be single thy whole body shall be full of light,” and later he says, “Enter ye in at the strait gate” … meaning the eye centre … “Because strait is the gate and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto life, and few there be that find it.”

Mystics are well aware of our fear of death, of the silence of the grave. So they show us how to make best use of silence and time, and teach us to listen to the Shabd and hear the word of God. They advise us to live a measured life, which balances our householder’s responsibilities and our meditational duty to the Lord, and so to honour the commitment to the inner path we made at the time of initiation.

The Seva Talks

The fictional diary of a young sevadar

A few years ago, when I had just started doing seva at one of the RSSB satsang properties, I was getting a lift home on Saturday evenings with one of my cousins and his uncle, a man we called Darji. ‘Darji’ is short for ‘Sardar Ji’, and I suppose he was considered to be a bit of a sardar in Punjabi society – an elder. I sometimes feel that in traditional societies there can be a lack of sympathy with the younger generation’s viewpoint, but Darji was never judgemental. There was a warmth in his eye and a friendliness that cut across all superficial boundaries.

I really liked Darji, and I liked the way the things he said got me thinking, so I used to jot down some of our talks afterwards. What he said made me appreciate seva better. When I came across my notebook the other day, my sister found me reading it, insisted on joining in – the way sisters do – and persuaded me to share it. So here are some of the pages:

Saturday 26 February

It was a very cold morning. We arrived at 8.30 a.m, checked in and had some tea, then we sat around waiting a very long time before the tools were found and the seva actually began. I felt bored, then critical, then angry with myself for feeling like that. When Darji asked me, on the way home, if I’d had a good day, I said yes (to be polite). Sandy, my cousin, was more forthright and said that the organization hadn’t been good.

Sandy: I’m not going to keep going, man, if they mess us about like that.

Darji: Oho! Spoken like a real lord. And I thought you were a humble sevadar, Sandy. But tell me: how would you organize it?

Sandy: Er … buy enough tools to go round. Have someone get them out earlier. Divide us into better groups …

Me: Introduce new people. Everyone seemed to know each other. I felt left out.

Darji: You should talk to the sevadar in charge.

Sandy: Why would he listen to us? We’ve only just joined that activity.

Darji: Are you saying that you need patience?

Sandy: No.

Me: Yes – I guess. Darji, are you saying that in time we would be able to make suggestions?

Darji: Why not, Ranj? Because, of course, Sandy’s right. How can those doing the difficult job of organizing take on board the comments of every newcomer? And, as a newcomer, how good a feel do you have for all the constraints? The people whose words are listened to are those who are trusted, who have given some service, weathered it out a bit …

Sandy: (sarcastically) … Sat around kicking their heels for a few hours.

Darji: Please apply the Alternative Test – don’t you know what that is? You should always apply the Alternative Test when you’re dissatisfied with something. Alright, you’re dissatisfied with the way you spent your time today. You think you may not want to put yourself inthis position again. So now decide on the alternative. How will you spend next Saturday? Will it be better? Will it solve the problems you discovered today? Come on, Ranj.

Me: Oh … okay. Well, next Saturday I suppose my alternative could be shopping and watching the football. If I’m truthful, it may be better in some ways – but may be worse in others. The problems I discovered today were, unfortunately, my intolerance, also the problems of organizing work for a lot of people. And no, staying home won’t solve them.

Darji: Well done, Professor!

At that we all began to laugh. Somehow, though it was never said, I think Sandy and I both remembered why we were going for seva in the first place. It isn’t, actually, to see perfect efficiency in action, is it?

Sunday 15 March

For the last two Saturdays, things have been better. I really enjoyed it yesterday. Going home in the car, I asked Darji, “Is seva for oneself or is it for the Master?”

Darji: Hmm … What do you think?

Sandy (indignantly): Well, it had better be for the Master, or else we’re all just wasting our time!

Me: Well, why does it say in the books, then, that seva is for our own benefit?

Darji: Why can’t it be both?

Me: Yes – I wouldn’t come here if I wasn’t motivated by wanting to give something.

Darji: And that feeling is something that helps you – I mean you, Ranj – ultimately.

Sandy: AND the work helps the Master – don’t forget that. That path I’ve just laid, that’s for him to walk over, not me.

Darji: Okay, Sandy, we hear you; we’ll make sure you have to walk in the mud!

Saturday 18 April

But today was awful. This guy at college had asked where I was going every weekend. After I got talking to him and told him about Sant Mat, and going for seva, he’d suggested that I was being exploited. Time and labour have a value, and no one should expect others to give it without payment – that was his opinion. I didn’t answer, because I already regretted opening up to him and I saw myself falling into another hole if I started saying that satsangis do find rewards in seva.

Then when we were mending a fence this morning, Sandy by mistake cut all the wire to the wrong length and it was wasted. The supervisor got angry – I mean really angry – and a couple of the boys spoke angrily back. Sandy walked away and didn’t reappear until it was time to go home. All the thoughts about exploitation resurfaced in my brain – I suppose the shine had gone out of the day’s work after that angry outburst.

Me: Darji, I thought satsangis were meant to have risen above anger and all that.

Darji: “Meant to” are the key words here. How long do you think it takes to control the mind?

Me: He shouldn’t be in charge of other people if he’s going to …

Darji: If he’s going to show that he’s at the same level as you and me? Come on, Ranj. I agree with you, of course: he was wrong. But don’t you also think you’re being a bit idealistic? We just don’t live in aperfect world and we can’t expect others to be perfect. But on the other hand, nor do you need to be cynical. Yes, I heard you talking to Sandy on the way here about whether we were all deluded stooges. Of course you’re not being exploited. We come here because we want to give freely of ourselves. Like we’ve discussed before, this is for our ultimate good and not the Master’s. We are in the process of learning to control ourselves, to work with others, put others first, and eventually to love. Because it’s a process, it’s highly unrealistic to expect perfect behaviour, even from those in charge. We all do our best and we must all support each other, whatever the odds.

With that, the car stopped at my front door and Darji said goodnight.

Sunday 26 April

Yesterday the supervisor who had got mad at Sandy came over and apologised to him. What’s more, Sandy said, “I’m sorry too. That’s cool: I wasn’t concentrating.” I said to Sandy afterwards, “You know what? You’re not bad really.” Sandy said, “I know.” And I said, “Now you’ve spoilt it, man.” But I was just joking. In the car going home, we talked to Darji again.

Sandy: I was upset when I got home last week. I thought maybe I’d get thrown out of the team.

Me: Well, I’m glad you felt like that. I thought you wouldn’t come back.

Sandy: The funny thing is, it made me realize how much this all means, how much I want to be part of it.

Darji: See how the Master hears our inmost thoughts. You take one step towards him – and that step can be taken in many different ways: in thinking it over, in feeling sorry, in sincere prayer, in reconciliation with the people you’ve offended – and he takes a hundred towards you. We think, ‘This person has spoken angrily to me; now this person has reconciled himself with me,’ but in fact the Master acts through others so as to teach us many lessons. If you don’t believe me, look in the books. In one of the letters in The Dawn of Light, the Great Master says that whatever good or bad happens to you proceeds directly from our loving Father – that all persons and objects are but tools in his hands. This understanding is what we get from seva. Just be happy, boys, that, as you say, you’re “part of it”.

Something To Think About

Theory and Practice

As the teacher was speaking with a group of children, a soap-maker attempted to embarrass him. “How can you claim that religion is good and valid when there is so much suffering and evil in the world? What good are all the books and sermons that your religion has produced?”

The teacher motioned to a small child to move through the crowd. “This is Eric,” the teacher said. “He is three. He is also dirty. I ask you, what good is soap when Eric and hundreds of children like him are dirty? How can you pretend that soap is effective?”

“What a foolish argument,” the soap maker protested. “If soap is to be effective it must be used.”

“Precisely,” the teacher answered. “If the teachings of our master are to be effective, they must be used.”

William R. White, Stories for the Journey

Instead of blaming the path or the Master, see within yourself where the weakness lies. Have you given regular time to meditation every day? Have you been able to keep the attention at the eye centre all the time during meditation?… Have you tried to live the Sant Mat way of life, detaching yourself gradually from the world and attaching your thoughts to the Lord within? In other words, have you followed the instructions given to you at the time of initiation? If we have not done our part, we cannot complain about the shortcomings of Sant Mat.

Maharaj Charan Singh, Quest for Light

Never Give Up

When we first come to the path, many of us experience a feeling of joy and relief. At last, the emptiness that seems to run invisibly under the skin of everything makes sense. We learn that the feeling of being an outsider, of being apart from things, of loneliness, has meaning and purpose. Whether conscious or unconscious, this feeling has sat within us, often since childhood, like a dull ache at the centre of our being, throbbing with an unceasing and alienating rhythm.

Is it any wonder, then, that when the Master accepts us into his fold we are filled with happiness? We finally understand that our affliction is merely one of the baits the saints use when reeling in their marked souls with the fishing rod of divine discontent. All we need to do is to follow our Master’s simple instructions in order to leave behind this world of vaporous illusion and to reclaim our divine heritage.

But as the ocean of time ceaselessly churns, the resolve and vigour with which we initially applied ourselves to the path are often worn down by the relentless tide of worldly impressions that assail us. It could hardly be any other way. We are physically bound to this world, our senses run out like wild horses, and we seem firmly trapped in a shadow land.

Our efforts at meditation become feeble, worldly commitments press in with vice-like force, and the noble teachings of the Master appear like a faint impression from a fading dream. We sometimes apply ourselves with only half-hearted effort to meditation, or abandon the struggle entirely, and may begin to compromise the vows we took at initiation.

But rather than seeing this as failure, we should understand that in fact we are in the midst of a transformative struggle, a fierce yet unseen battle that demands all our attention and endeavour, a conflict that makes even the most difficult of worldly challenges appear easy. In comparison, to make a million dollars is child’s play and to scale the most dangerous of mountain peaks the stuff of nursery rhymes. If we are wavering and if our commitment is dissolving like melting snow, then this is precisely the point at which we should stand firm and refuse to be beaten.

There is an instructive tale from Scottish folklore, concerning Robert the Bruce, a king of Scotland who reigned in the fourteenth century. He was determined to free his people from the yoke of submission to the English king. Five times the English and Scottish armies clashed, and five times the Scots lost to their more powerful foe. After the fifth defeat, the Scottish king had to flee for his life. He spent a grim winter in a wretched hut on an island off the coast of Northern Ireland.

Robert the Bruce felt at this point that he was a beaten man. However, one day he noticed a spider in the hut, spinning a web. The spider kept failing in its innumerable attempts to spin a thread between two wooden beams. But it never gave up and eventually managed to span the distance and complete its web. Inspired and galvanized by observing the indomitable will of this tiny creature, the king resolved to return to Scotland and raise another army. Despite being outnumbered by a ratio of three to one, his army defeated the English, and Scotland was finally granted independence.

Yet this is a tale of mere worldly success. What we have committed to is of infinitely more value. The spiritual path is one of courage, selfless sacrifice and elevating endeavour. The world will not offer us praise or encouragement in our struggle, it will not fete us for our unwavering will, and we will receive no shimmering awards for slaying the dragon of the mind. Rather, the world will quietly turn away from us – or even laugh openly at our spiritual ambitions. That is how it is bound to be, for this sphere is naturally inimical to spiritual effort.

But we should never give up. A boxer does not climb into the ring anticipating defeat. He takes to the canvas knowing that he will face punishing blows, certain that he will be hurt, understanding that his stamina and skill will be pushed to their limits. But he also enters the ring with a plan in mind of how to outwit his opponent and claim victory. And despite months of intense training to build stamina and develop technique, he knows that ultimately success will depend principally on one factor: the will to achieve victory, whatever the odds.

Our will is a powerful force, and by using this determination in applying ourselves to simran we are fuelling the fire of success in meditation. It is worth remembering that many who have gone before us have achieved such success, and that behind stand many more who too will scale the invisible heights with quiet, unseen glory. Why should we ourselves not join this stream of ascending light? As the saints have pointed out countless times, this is our birthright.

Since being brought into the Master’s orbit and starting on the path, the obstacles we have faced and the difficult karmas we may on occasion have had to endure can dilute our resolve. But we should never let them break us. They can, rather, increase our strength, for the more suffering we go through, the lighter our load becomes. And the lighter we become, ultimately the higher we rise.

Moreover, beneath the layered crusts of our being we have the hearts of lions. If we did not, the Master would never have initiated us. If he thought we lacked the strength to banish the shadows of this world and rise above this ceaselessly oscillating illusion, then we would never even know of the path of the Masters. Let us not forget this. Let us never lose heart.

And now here is my secret, a very simple secret: It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.… Men have forgotten this truth.… But you must not forget it.

Antoine de Saint-Exupery, The Little Prince

Questions and Answers on Meditation

Maharaj Charan Singh answers satsangis’ questions on meditation in Die to Live

Q: Maharaj Ji, I think it was Jagat Singh Ji Maharaj who said, “Eat less, sleep less, speak less,” and I’ve had a question: I understand the eat less and I understand the speak less, but I don’t understand the sleep less, because when I sleep less, it seems to interfere with my meditation. Could you explain that?

A: You should control your sleep. We shouldn’t try to sit in meditation at the cost of sleep. We should cut down other engagements of our life, but the body must have six to seven hours sleep.…

“Sleep less” means that you shouldn’t unnecessarily go on sleeping. Some people sleep ten hours or twelve hours, so for them, six or seven hours is less. If you will eat less, you will automatically sleep less. If you will speak less, the mind will not be so scattered. Speaking tires you and scatters the mind, and eating too much makes you sluggish.

Q. In the Indian scriptures the hours between 3 a.m. and 6 a.m., or generally the hours of the early morning, are called the “nectar hour”. Is there an inner mystic advantage to that hour?

A: No, no. I follow your point. There’s no particular time for meditation. Whatever time you can attend to meditation is to your credit, but the morning time has certain advantages over other times. When you get up in the morning, the first thing is you are absolutely fresh. Your tiredness is gone. Your mind is not scattered, and you are not distracted by outside disturbances. There’s no telephone ring, there’s no knock at the door and there’s no hustle and bustle of traffic outside. So it’s a quiet time. And then, when you are going to start a day, why not start it in the name of the Father? That atmosphere of bliss which you build by meditation should go with you the whole day to help you face the ups and downs of life without losing your balance.

Q: If one wakes up, let’s say, at one or two o’ clock and is very refreshed, and you know that if you’re going to get up and sit for meditation, you have to go back to bed again before six or seven o’ clock, is it better to try to sleep and then get up again later, or still to get up and take advantage of the time, knowing you’re going to have to go back to sleep again?

A: Do take advantage of that time and attend to meditation. No opportunity for meditation should ever be lost under any circumstances. After that there is no harm in going to sleep.

Q: Is it better, if it’s possible, to sit without leaning against something?

A: The main thing is, our spine should be straight, from the health point of view, from the alertness point of view. If your backbone is straight, you’re more alert and you are not easily lured to sleep. But if your back stoops when you sit, then there’s always a danger of getting sleepy, and if we lean against something, sometimes the backbone is not straight. Even if you work sitting in a chair and your backbone is straight, you can work much better. The main thing is, one should try to keep the spine straight.

Q: I’ve heard that meditation on a full stomach is harmful because in meditation the blood goes to the head and therefore does not allow the food to properly digest. Is this true?

A: We don’t say meditation is harmful, but if you meditate with a full stomach, you may feel sleepy. Otherwise, you can do meditation at any time – with a full stomach, with an empty stomach; it is all right. But naturally with a heavy stomach you’ll be yawning, you will go to sleep, you’ll be lazy, so you may not be able to concentrate.

Q: If we sit for meditation, but in the two and a half hours we fall asleep for part of the meditation, and if we don’t try to make up that part during the rest of the day, is that breaking the vow to do two and a half?

A: Brother, the vow means that it is our good intention to give that much time to meditation. That is the vow. But when we take a vow on ourselves and we don’t attend to meditation, we carry a sense of guilt, that we have not done our duty. That sense of guilt will help you to sit in meditation again, and then you will be able to give more time to meditation. But don’t be too rigid about these things. If you have not been able to give the full time in the morning, give more at noon or in the evening, whenever you feel like.

Q: Maharaj Ji, it is often said that we should do more meditation with punctuality, regularity, and love and devotion. But love and devotion seem to be out of our hands.

A: Unless you have that faith, you will never practise meditation. If I know that a road leads to New York from Washington, I’ll go on driving at full speed. If I have no faith that the road will go to New York and I feel that it may go in some other direction, it becomes very hard for me to drive. I have to ask people for directions at every step. Sometimes I look at the map, sometimes I look at the road signs, sometimes I ask pedestrians; then I go astray.

Faith doesn’t take you to the destination. Practice will take you to the destination, but faith will make you practise. Without faith, you can’t practise. You will not be able to drive at full speed without faith. Full speed will take you to the destination, but faith is helping you to drive at full speed. Similarly, love and devotion is to have faith in the path and the Master. Then we practise also, and then we get the results from that practice.

Being between Now and Eternity

As spiritual seekers, one of the goals to which we aspire is the unchanging truth. Until we reach the state of knowing that is eternal, our biggest problem is how to conduct our lives from where we are now. We have a teacher, a practice, literature and satsang to help us. We have no certainty of knowledge about any of these until we experience for ourselves their spiritual significance. Until then, all of life is a set of assumptions and adopted teachings whose ultimate value we cannot judge. We need better guidelines than our material cultures and traditions give us.

We have to negotiate our lives from the time we start seeking until we realize the eternal, and this may be the full lifetime or more. The issue is how to be at each moment. The formula is to act in the name of the Lord, but our problem is the interpretation of that formula. What we need is an approach to living that will embody the spiritual aspect so that our lives attune us to the state at which we aim. It is received wisdom that spirituality has to be incorporated in one’s lifestyle and habits for it to take root. It cannot just be attained overnight.

Maharaj Charan Singh said in Quest for Light: “We are an expression of infinite life which had no beginning and shall never come to an end.” We wish to realize this inspiration for ourselves, so that, through awareness of our unity with all that exists, being free of limitation or ignorance, we may know how to be, and what it is that we are.

The saints tell us that in the court of the Lord there is nothing but forgiveness. Our ultimate goal is to enter and be part of that. So, we must constantly aspire to this ideal by maintaining the effort to be forgiving. We need to practise forgiveness, so that we can continue to gain awareness of the Lord whose nature is unqualified forgiveness.

In A Course in Miracles it says:

In your brother you see the picture of your own belief in what the will of God must be for you. In your forgiveness will you understand His love for you.

Since everything that exists has been created by God’s ordinance and thus is his doing, it is sustained in his being and so part of him. Nothing made is less than God – there is nothing else. We should be present to the divinity in the creation because all is God; all is blessed and all is a teaching of the presence of the Creator. As Maharaj Charan Singh says in Quest for Light:

… no one does us any wrong or treats us badly. According to the layer of our karmas that comes into action, our Lord makes people act towards us in that way. So, we should never blame anybody.

The practical application of this means to forgive – both others and self. It implies a way of looking at things that allows us to absorb them not by classifying them into the learned categories by which we judge, but to be receptive to the possibility that they are an expression of the divine. Through this we come to a different insight into the physical plane and how it manifests.

It has been said that nothing is good or bad, except our judgements make it so. This supports the principle that all things are beyond our judgement, that they are an expression of the Lord’s will, which brought them into being, and as such are given to us to learn from. What makes us think otherwise is the sense of separation by which we identify the self or the ego.

It follows that what we experience is what we filter through our wishful thinking, the false beliefs that we have learned since birth and before. This is what the saints teach us. This means that everything we experience as falling short of the divine, everything we think we control, everything we think we own or can define or achieve through our own direction, is an illusion that we ourselves make. For most of us, the world we see is one we fabricate in our own perception.

The path we follow is one of correction of this most profound of errors. If we are able to form an impression of the world apart from its Creator – which is exactly what the vast majority of us have done – then it follows that we are able to change how we perceive the world. We are asked to do this: to build an atmosphere in our lives that is receptive to the divinity within. In the same sense that we practise meditation while being receptive to the real experience that will come by grace, we have to practise openness to God’s presence in the world of perception until that becomes our experience.

Maharaj Charan Singh says in Spiritual Discourses I:

The clay of which we are all made is the same. The forms alone differ. … Disdain no man, for to disdain man is to disdain God himself within that man. And to disdain God in any man is to disdain Him in oneself. How shall one ever reach his haven if he scorns his only Pilot to that haven?

We need to grasp that the God in each of us is the same God in our fellows. There are no pieces of God allocated separately to individuals. There is one God.

We also need to come to terms with the principle that the Lord in each of us is the entire Godhead, harbouring the totality of the creation. We see ourselves as pieces of the Lord, distinct in our selfhood and adrift in the vastness of time and space. If we are able to exercise our true awareness, we will see nothing other than the Lord, and in every aspect and every manifestation of him, his entirety – the universe in a grain of sand, the full Godhead in our fellow human beings and, equally, in ourselves. Such is the power of his making.

Since the Lord, being unlimited, has no need of time – it being our chosen millstone – his accomplishment is infinite in scope and limitlessly free of the proceedings of time. All is already created; all is already done. His works are complete, unconstrained by any dependence on human development for their attainment. If we see our fellow beings correctly, we will see them as expressions of God. This is because there is only one God, perfectly encompassed in each being as the totality.

As Rumi has said, the Lord sees in us our final flowering, because he is not encumbered by time and its limitations. He sees in the seed the mature plant; in the wish to be, the final fulfilment of that wish. Not in imagination, as we might, but he sees in reality beyond time the living manifestation of both seed and maturity, wish and fulfilment.

In brief, that which is our final cup is really our name with God ….

He bestows on a man a name according to his last flowering.

The Mathnawi, translated by Reynolds & Nicholson

We are taught that the Masters do not judge us by our faults – these are part of our surface attributes, which purification will eliminate. They see us in the light of God’s cosmic design, free of the constraints of time and place – as aspects dancing to the profound chorus of his limitless creation. They tell us we are manifestations of the Lord, as are they, and are tuning us to be worthy of that.

The medium through which this is done is love – the ultimate binding force, which admits of no distinction, which judges not, which accepts all unto infinity as God. This is how thoughts are sustained in the mind of God, in whose court, the Masters tell us, is nothing but forgiveness. If there is only forgiveness, there is no judgement, there is no distinction. All is equal and equally valued.

We have to show our willingness to be raised up by putting in the effort to align ourselves with the requirements of the path. We must become receptive to his presence at all times and this will be reflected in our actions. It is this turning towards the Lord that invokes his grace. It is this grace that accomplishes liberation and union. That this will happen is assured.

Tolerance and patience with courage are not signs of failure but signs of victory. In your daily life, as you learn more patience, more tolerance with wisdom and courage, you will see it is the true source of success. Actually, if you are too important, that’s a real failure.

The Dalai Lama’s Book of Wisdom, edited by Matthew Bunson

Describing the Indescribable

I am bewildered by the magnificence of your beauty and wish to see you with a hundred eyes. My heart has burned with passion and has searched forever for this wondrous beauty that I now behold. I am ashamed to call this love human and afraid of God to call it divine. Your fragrant breath like the morning breeze has come to the stillness of the garden. You have breathed new life into me. I have become your sunshine and also your shadow. My soul is screaming in ecstasy. Every fibre of my being is in love with you. Your effulgence has lit a fire in my heart and you have made radiant for me the earth and sky.

The Love Poems of Rumi, translated by D. Chopra

These lines from the Persian mystic Jalal ud-din Rumi, attempting to describe the inner beauty of his own Master, serve to remind us of our immediate goal: to come face to face with our Master inside. Maharaj Sawan Singh talks about this experience in Philosophy of the Masters Vol I, and refers to Hafiz’s similar attempts to describe the radiance of the inner Master:

We are wonder-struck to hear descriptions of the beautiful physical form of the Master, but if we manifest him within, we will find him a thousandfold more beautiful. Hafiz, addressing the Lord, says:

O Beloved, I have heard many a tale

about your wondrous beauty;

But now that I have beheld you within, I see that you are really

a thousand times more wonderful than the tales depict you.…

Hafiz has attempted to portray this inner vision, but how can one describe what is indescribable? He says:

The whole night his refulgence filled my heart with light.

What a bold thief he is to come in the darkness,

But with what an aura of radiance he comes!

The mystic poetry of Hafiz and Rumi is nothing more than an attempt to describe the indescribable.

Rumi attempts to describe the greatness of his Master, Shams-e-Tabriz, in the following words:

O infinite love, O divine manifestation, you are both stay and refuge; an epithet equal to you have not heard. We are iron filings and your love is the magnet; you are the source of all questing.… Be silent, brother, dismiss learning and culture …

Mystical Poems of Rumi 2, translated by A. J. Arberry

Note how Rumi puts learning and culture into perspective. In this world they are held in high esteem, but for a seeker on the spiritual path they are in fact obstacles. The problem with adding more and more to our store of knowledge and experience is that the eventual, inevitable taking away of all these additions becomes greater and greater as well. The trick is not to become attached to all this learning.

The Master tells us that we spend too much of our time on trivial things. If we examine our actions in any 24-hour period, it will look like an exercise in futility. We should know better than to waste our time in this way. If someone is ignorant of the true purpose of life, you can hardly blame him for leading a life of futility, but we have no such excuse, because for us the Master has lifted the veil.

Yet we act on a daily basis as if nothing has happened to reveal to us the truth of our existence. Part of this is to do with completing our karma – unless we act from ignorance we would not do certain things that we have to do in order to complete our karmic interaction with other people. Nevertheless, we should endeavour to become ever more conscious, through meditation and living at the eye centre, so that even while acting out our karmas we can be an observer as well as an actor.

Those around us can of course misunderstand this distancing of ourselves from everyday events, and we can be accused of making light of a serious situation, or even of not being happy enough when everyone around us is shrieking with delight. Emotionally jumping up and down in ecstasy or distress is how most people react to ‘good’ or ‘bad’ news, but we, with time, can learn to see this so-called good and bad as just ‘what is’ – or, if we’ve really grasped the truth, God’s will, or the Lord’s grace. How could it be otherwise?

There is no doubt about it: it is not easy to live in this world. This is something that Rumi well understood:

The world was no festival for me; I beheld its ugliness, that [pallid] wanton puts rouge on her face.…

Unlucky and heavy of soul is he who seeks fortune from her.

… Come to our aid, Beloved, amongst the heavy-hearted, you who brought us into this wheel out of non-existence.

Mystical Poems of Rumi 2, translated by A. J. Arberry

He makes the point that the world appears attractive only through the deceptive effects of superficial cosmetics, but without the Master’s help our mind cannot see through these charms. We are functioning on the mind’s autopilot, which repeatedly pulls us back to the creation. The Master has shown us how to flick the switch over to give control instead to the soul, which takes us to the eye centre and beyond at every opportunity. So are we going to flick that switch and enjoy the bliss of the inner worlds, or are we going to be satisfied with the thrills and spills of the material world? It’s our choice.

The Masters refer to the ‘mistakes’ we make, the bad judgement calls, rather than to ‘sin’. There is more or less a constant struggle with one or more of our five enemies – lust, anger, greed, attachment and ego. But for a satsangi, the only real ‘sin’ is what Maharaj Charan Singh, quoting Jesus Christ, referred to as sinning against the Holy Ghost – turning your back on meditation. He even said that this would not be forgiven.

This is very serious: the all-forgiving Lord is displeased when we turn our face away from him. “But I don’t turn my face away from him!” we cry. Don’t we? Aren’t we generally facing away from him and just occasionally turning towards him when it suits us, when we cannot cope with life? If that is what it takes for him to get our attention, he may shower us with crises. Better to remember him at all times, for without meditation we are up the creek without a paddle. Meditation is actually the paddle that propels us towards our goal, steering us around – or maybe through – obstacles.

Difficulties will not disappear but they will become bearable when we remember the Lord and our purpose here. Rumi says:

Every day I bear a burden, and I bear this calamity for a purpose: I bear the discomfort of cold and December’s snow in hope of spring…. I bear the arrogance of every stonehearted stranger for the sake of a friend, of one long-suffering; For the sake of his ruby I dig out mountain and mine; for the sake of that rose-laden one I endure a thorn. For the sake of those two intoxicating eyes of his, like the intoxicated I endure crop sickness.

Mystical Poems of Rumi 2, translated by A.J. Arberry

Elsewhere he says:

Rise, lovers, that we may go towards heaven; we have seen this world, so let us go to that world. No, no, for though these two gardens are beautiful and fair, let us pass beyond these two, and go to that Gardener.… Let us journey from this street of mourning to the wedding feast, let us go from this saffron face to the face of the Judas tree blossom.… There is no escape from pain, since we are in exile.… It is a road full of tribulation, but love is the guide, giving us instruction how we should go thereon.

Mystical Poems of Rumi 2, translated by A. J. Arberry

He says that we have seen all that this world has to offer and found it wanting, so let us set out for the inner world. The gardens are indeed beautiful, but let us go to be with the Creator (the Gardener), not the creation. This world is a place of death and sorrow, so he urges us to go to the realms of pure joy. In this world, pain and suffering are inevitable, but fortunately we have a spiritual guide who counsels us every step of the way.

We have been told it is our expectations that cause us pain and suffering. At the highest level, the path of Sant Mat is the journey of the soul from the darkness of illusion to the brightness of reunion with the Lord. At a more mundane level there is another journey: the journey of the mind from high expectations to low expectations and, finally, no expectations.

We are also told that we should reflect rather than react – we should not over-react to negative or positive stimuli but just keep our equanimity.

Maharaj Charan Singh writes in Quest for Light:

Nobody ever does us any good or bad thing, nor can any person offer us insult or bestow honour on us. The Master moves the strings from inside and makes people behave towards us according to our karmas. All insults or loving attention come to us as a result of our own actions – sometimes from a previous life and sometimes from the present life. So do not take too much to heart the behaviour of other people towards you.

He continues:

Cease from men and look above thee. Love the Lord … let not your pleasure and worry depend on the attitude of others.

Inevitably, he finishes with the words, “Attend to your meditation regularly.”

Life may be extremely demanding and challenging at times but, thank God, like Hafiz, we have a Master to accompany us on life’s journey. Hafiz says:

When the face of God appears before your eye,

Then you may be sure that you have true vision.

In Search of Hafiz, translated by A. J. Alston

Ultimately, we do not need to attempt to describe the indescribable. All we need to do is what our Master has asked us to do: our meditation. When a satsangi once asked a friend who had recently attended a satsang with the Master what had been said, the reply was simply: “He said to meditate!” Although it is indescribable, it is achievable.

Book Review

Siddhartha

By Hermann Hesse. Translated from German By Hilda Rosner

Publisher: BanTam Books, new york, 1971, c1951.

ISBN 0-553-20884-5 (PBK)

In 1922 a small novel with the ancient title Siddhartha appeared in European bookstores. Though its author, the German poet and novelist Hermann Hesse (1877–1962), later earned the Nobel Prize in Literature for the novel Magister Ludi (The Glass Bead Game), Siddhartha remains his most famous novel. In it Hesse draws on his childhood experiences as the son of missionaries in India to transport us to India in the time of Gautama Buddha.

The novel tells the story of a fictional Siddhartha, the son of a Brahmin priest, who, despite the fortunate circumstances into which he was born, leaves home to seek truth. Hesse aptly defines the protagonist’s role by the name he chooses for him: “Siddhartha”, composed of the roots siddh– to accomplish or to succeed – and artha– an object or aim. Siddhartha’s story becomes a parable of Everyman and Everywoman on the long-turning wheel of transmigration.

A central event in the story is Siddhartha’s encounter with the spiritual adept Gautama Buddha. For the same reasons that he had abandoned the religious doctrines of his forefathers, the Hindu Brahmins, Siddhartha declines to adopt the teachings even of a living saint, believing that enlightenment comes only from personal experience, from individual trial and error. On meeting the Buddha, Siddhartha acknowledges his perfection but still challenges him: “To nobody, O Illustrious One, can you communicate in words and teachings, what happened to you in the hour of your enlightenment.” The Buddha does not respond, but warns Siddhartha “to be on your guard against too much cleverness”.

Paradoxically, throughout the story, teachers impart their knowledge to Siddhartha. But as one teacher reflects:

Which father, which teacher, could prevent him from living his own life, from soiling himself with life, from loading himself with sin, from swallowing the bitter drink himself, from finding his own path? Do you think, my dear friend, that anybody is spared this path? But if you were to die ten times for him, you would not alter his destiny in the slightest.

Siddhartha explores various probable and improbable approaches to truth – asceticism, sensuality, a father’s love for his son – and experiences each to extremes. Ironically, he reaches old age and still has failed to achieve his objective. Almost twenty years after his encounter with the Buddha, after exhausting himself in asceticism and sensuality, he experiences a “terrible emptiness of the soul”. Drawn to a ferryman called Vasudeva, he becomes his apprentice.

Throughout the novel, water, particularly the river, appears as a power purifying the individual and revealing the mysteries of the universe. Siddhartha sits by the river, and Vasudeva encourages him to learn from it. “Above all, he learned from it how to listen, to listen with a still heart, with a waiting, open soul, without passion, without desire, without judgment, without opinions.”

Listening to the river, Siddhartha discovers that time is an illusion. Vasudeva agrees:

A bright smile spread over Vasudeva’s face. ‘Yes, Siddhartha,’ he said. ‘Is this what you mean? That the river is everywhere at the same time, at the source and at the mouth, at the waterfall, at the ferry, at the current, in the ocean and in the mountains, everywhere, and that the present only exists for it, not the shadow of the past, nor the shadow of the future.’

Still, when Siddhartha meets his young son for the first time, he loses himself in an over-fond, doting love. Once again, he goes to the extreme. This powerful, blind attachment, along with the excruciating pain it brings, teaches Siddhartha another lesson. The people he ferried across the river “no longer seemed alien to him as they once had”. Rather, he felt they were his brothers.

Their vanities, desires and trivialities no longer seemed absurd to him.… He saw life, vitality, the indestructible and Brahman in all their needs and desires. These people were worthy of love and admiration in their blind loyalty, their blind strength and tenacity.

Unable to overcome either his attachment or his painful, negative emotions, Siddhartha breaks down and tells Vasudeva of his condition. Motionless and serene, Vasudeva listens.

Disclosing his wound to this listener was like bathing it in the river, until it became cool and one with the river.… He felt that this motionless listener was absorbing his confession as a tree absorbs the rain, that this motionless man was the river itself, that he was God himself, that he was eternity itself.

Siddhartha comes to realize a key spiritual truth: that no matter how far the seeker travels on his way, the spiritual quest is not a journey. He says:

The sinner is not on the way to a Buddha-like state; he is not evolving, although our thinking cannot conceive things otherwise. No, the potential Buddha already exists in the sinner; his future is already there. The potential hidden Buddha must be recognized in him, in you, in everybody.

Siddhartha realizes that:

When someone is seeking.… it happens quite easily that he only sees the thing that he is seeking; that he is unable to find anything, unable to absorb anything, because he is only thinking of the thing he is seeking, because he has a goal, because he is obsessed with his goal. Seeking means: to have a goal; but finding means: to be free, to be receptive, to have no goal.

Ultimately, from the river and from Vasudeva, Siddhartha learns to let go – let go of desires, let go of quests, let go of himself.

From that hour Siddhartha ceased to fight against his destiny. There shone in his face the serenity of knowledge, of one who is no longer confronted with conflict of desires, who has found salvation, who is in harmony with the stream of events, with the stream of life, full of sympathy and compassion, surrendering himself to the stream, belonging to the unity of all things.