The Mystic Heart of Judaism

Miriam Bokser Caravella

PREFACE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

INTRODUCTION: Revelation and Concealment

Divine unity

Divine language

Inner journey and mystical experience

Conclusion

CLASSIC TEXTS OF JUDAISM

Talmud and Midrash

Editions used

TRANSLITERATION GUIDE

EDITORIAL NOTE

- In the Beginning...

Abraham

Moses: The archetypal prophet

Joshua - Early Prophets

Samuel

David: The prophet- king

Prophets and their disciples

Elijah and Elisha: The ecstatics - The Classical Prophets

Amos: Seek the Lord and live

Hosea: The husband betrayed

Isaiah: A vision of holiness

Jeremiah: A message of comfort

Ezekiel: Visionary of the chariot of God

Second Isaiah and Third Isaiah: Polished arrow and servant of God

The concept of the messiah - The End of Prophecy?

Mystic masters at Qumran

1 Enoch

Concept of the messiah at Qumran

End of prophecy? A postscript - Sages and Rabbis

Jesus of Nazareth

The rabbis at Yavneh and Tiberias

Babylonia - Magic and Mystic Ascent

Rabbi as miracle worker

The power of numbers, letters, and names

The merkavah and the power of names

The Sefer yetsirah - Early Messiahs

Abu Isa

Yudghan and Mushka - Philosophers and Sufis

Jews in the world of Islam

The Maimonides family

Abraham he-Hasid and the Maimonides family

Practices - The Middle Ages: Hasidei Ashkenaz

Teachings of the Hasidei Ashkenaz

The Special Cherub circle

Practice

Conclusion - The Middle Ages: Early Kabbalah

The Bahir

First kabbalists in Provençe and Gerona

How did the mystics live? Renunciates and ascetics

How the teachings were revealed and passed down

Symbolism of the early Kabbalah

Kavanah and devekut

The Gerona circle

The Iyun circle

A mystical rationale for the commandments - The Kabbalah Matures

Moses de León

Abraham Abulafia - The Mystic Fellowship of Safed

Moses Cordovero

Isaac Luria - Messiahs of the Post-Inquisition Age

David Reubeni and Shlomo Molkho

Shabatai Tsevi

Jacob Frank

Moshe Hayim Luzzatto

Yemenite messiahs

A return to inwardness - Hasidism: A New Paradigm

The tsadik as foundation of the world

Social background

The Ba’al Shem Tov

Ba’alei shem: Masters of the name

Disciples

The doctrine of the tsadik

Teachings

Fountain of grace and wisdom

The court of the rebbe

Rabbi Nahman of Bratslav

Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Lyady and Habad- Lubavitch

Other tsadikim

The unending story

APPENDIX 1: The Writing of the Bible

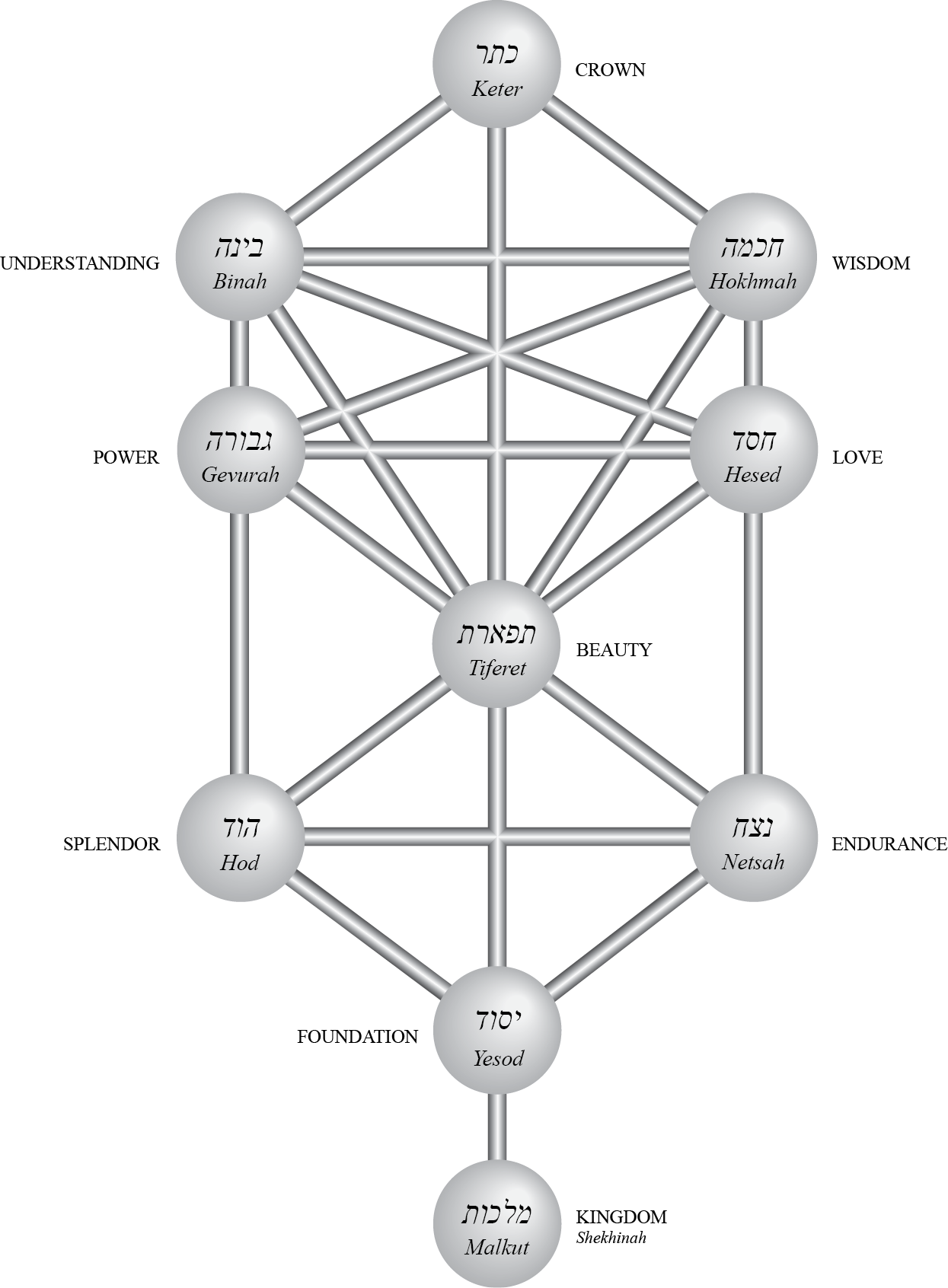

APPENDIX 2: The Sefirot

APPENDIX 3: Theurgy and Augmentation in Hasidei Ashkenaz and Early Kabbalah

APPENDIX 4: Testimony of Abulafia’s Disciple

ENDNOTES

GLOSSARY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Contact and General Information

Published by:

G. P. S. Bhalla, Secretary

Science of the Soul Research Centre

c/o Radha Soami Satsang Beas

5 Guru Ravi Dass Marg, Pusa Road

New Delhi 110 005, India

© 2011 Science of the Soul Research Centre

All rights reserved.

First edition 2011

ISBN 978-93-80077-16-1

PREFACE

THE SEARCH FOR SPIRITUAL INSPIRATION and understanding is universal. Although there have been periods in history when the idea of the divine has become externalized, grounded in the material and the secular, there have always been those people whose direct experience of the mystical reality proved otherwise. Most recently in Europe, the eighteenth, nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries saw a rejection of the mystical in favor of social, material, intellectual, and scientific progress. In Judaism this tendency gained great strength under the name of the Enlightenment, the Haskalah, which promised release from the insularity of the Jewish community vis-à-vis the dominant Christian society.

Yet at the same time, the explosion of Hasidism as an expression of the belief in the mystical and the essential importance of the spiritual master, the tsadik, in attaining soul liberation, counterbalanced this materialistic tendency. Indeed, personal direct experience of the divine through the intervention or inspiration of a spiritual master has always been accepted by devotional groups within Judaism. Perhaps because of the waves of persecutions the Jews had experienced in European society over the centuries, Jews had developed a tendency to look inwards for their sustenance and strength. In this milieu, many great spiritual leaders appeared, mystics and moralists who gave form to their spiritual practices and developed complex systems of meditation and mystical symbolism.

By the mid-twentieth century, the intellectual Jew was careful not to abandon himself to emotional or ecstatic types of worship, nor to acknowledge the beauty and inspiration offered by the complex symbolism of the kabbalists. The modern intellectual regarded the mystical as mysterious, confusing, and somehow untrustworthy. For the mainstream religious Jew of western society, God became an abstraction rather than a living being. As a transcendent abstraction he could not answer prayers. For the intellectual, there was no room for a living spiritual master, a teacher who could put his disciples in touch with the divine holy spirit, the ruah ha-kodesh of the Bible. Anyone could have access to the abstract divine being – intermediaries not needed and not welcome – or at least this was the maxim taught to the masses and the youth.

In recent years, Judaism has moved on towards a more mystical approach. No longer is there shame associated with devotional ecstasy. Attitudes often reflect a cyclical spiral, and so today there is a “renewal” movement in Judaism that has brought many people in touch with the mystical nature of their being. These are people seeking a more immediate experience of God, who invest their religion with renewed hope for spiritual transformation. They are not afraid to seek masters, leaders, rebbes, tsadiks, holy men and women, under whose wings they can grow towards a first-hand experience of God.

In 1977, the noted scholar and practitioner of Jewish mysticism, Arthur Green, anticipated this shift in attitudes when he wrote his article “The Zaddiq [tsadik] as Axis Mundi in Later Judaism.” In this article, he explodes the myth that in Judaism there are no holy persons who bring the divine reality to the human level. He discusses the history of the concept of the tsadik as the pillar who connects heaven and earth, divine and mundane, who is the source of all blessings that flow to man on earth, and who acts as the channel through which man can return to the divine. Green recounts how various contemporary scholars have corrected this one-sided presentation of the religion and have demonstrated “the perseverance with which myths of sacred persons survived and developed in the literature of later Judaism.”1

The purpose of this book is to rediscover the spiritual masters of Jewish history whose teachings have brought inspiration and spiritual solace to generations of Jews – from the prophets of the biblical period through the mystics and rabbis of antiquity; to the hasidim (pietists) of Germany, the Sufis, and kabbalists of the Middle Ages; to the messiah figures of all periods, later kabbalists and wonder workers, and finally to the tsadikim of Eastern European Hasidism.

The spiritual level attained by these individuals will always remain a mystery for us, both because of limitations of our own experience and the impossibility of assessing another person’s spiritual experience. The depth and degree of their influence on their disciples also would have varied according to the receptivity of those disciples. The dominant threads, however, we can discern: the yearning for spiritual understanding, for closeness to God, relief from the sufferings of the material world – all these the living spiritual masters shared. The richness of the literature they left behind is a witness to the great creative surge that the inner spiritual quest inspires.

It is my own experience with a living spiritual master that has inspired me to dive into these three millennia of Jewish life to bring to the surface the evidence of those great teachers and mystics who dedicated their lives, physically and spiritually, to continually renew the heart and soul of Judaism. They have been a channel for the divine power to enter the physical realm of human life, and a ladder through which others might ascend and experience the divine.

Working on this book has given me the opportunity to focus on the mystic heart of my own inheritance. It has been inspiring to discover the continuum of voices within Judaism that resonate with the voices of the great spiritual leaders and masters of other ways and paths to God. It is this discovery that has been thrilling and humbling for me, with my deep roots in Judaism, as I have researched material for this book.

In essence, this book is concerned with the universality of spiritual truth as expressed through the Jewish experience. In its natural unfolding as a mostly chronological study, The Mystic Heart of Judaism attempts to demonstrate the primacy of the spiritual master as the teacher and transmitter of truth. It presents the living teachers and their living teachings, their inner spiritual life with the divine, their relationship of love with their disciples.

It is my hope that this book will be of value particularly to other readers with a Jewish heritage who are searching within their tradition for knowledge of the one God who is common to all humanity. And if their search takes them to a living spiritual master who can inspire and guide them on the path of mystic awakening, they will be most fortunate.

The twenty-first century is witnessing a growing dialogue among adherents of the world’s religions as they explore their common foundation of spirituality while respecting the differences arising from history and culture. It is hoped that this book will make a positive contribution to that dialogue by bringing to light the perspectives of Judaism’s great spiritual teachers and mystics.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I WISH TO THANK all those who have so generously helped me complete this work by sharing their insights, reflections, and encouragement. Through this project, I have gained the invaluable friendship of such illustrious scholars as Joseph Dan, Rachel Elior, Immanuel Etkes, Eitan Fishbane, Michael Gottsegen, Menahem Kalus, and Jacob Neusner. I have been greatly enriched by having had personal contact and correspondence with them, and I look forward to a continued dialogue with this fountain of knowledge and light.

I also wish to acknowledge with fondness the contribution of the late Steve Segal, who assisted me with the initial research on the kabbalists discussed in this book.

INTRODUCTION

Revelation and Concealment

THE HEBREW WORD OLAM, meaning “world,” is thought to derive from the same root as the word “to conceal” (le-ha’alim). Mystics are those who, while living in the olam, see through its illusion of substance to the eternal, divine reality it conceals. Like pearl divers who plunge to the depths of the ocean, they retrieve the pearl of pure spirituality and share their wisdom with humanity. Throughout the millennia of Jewish history, every generation has given birth to mystics who have sought the great spiritual treasure that is concealed within the revealed.

Mystical practice is like a fine thread that runs through the entire history of the Jewish people. From the earliest biblical accounts of the patriarchs conversing with God, to the prophets’ passionate commitment to their divine mission, to the merkavah mystic’s inner journeys to supernal realms*, to the kabbalists’ creation of complex meditation practices*, Judaism has always been enriched by these courageous souls, fired by longing for the divine, who let no obstacle stop them in their quest.

Through its 4,000-year history, Jewish mysticism has taken many different forms. At times it has been highly devotional and ecstatic; at other times it has been extremely intellectual. At times it was the solace of small groups of kabbalists who kept awake night after night in study and meditation; later it became the manifested joy of the hasidim who made it available to the entire Jewish community.* Additionally, because the Jewish people have lived as a minority among adherents of different religions and cultural traditions, the Jewish mystical experience reflects its exposure to these distinct influences. In Western Europe, Jews came in contact with Christian concepts of God, including its feminine aspect, the Virgin Mary, contributing to the development of the concept of the Shekhinah – the feminine, immanent aspect of God. Austere Christian monastic traditions also influenced Jewish mystics and practitioners in the Middle Ages. And when Jews came in contact with Muslims settled in Palestine, North Africa, and Spain, they absorbed elements of Neoplatonism and Sufi mystical practice, to the point where some Jewish writings are nearly indistinguishable from those written by Muslim mystics. Jewish mystics also traveled widely around the Mediterranean and influenced one another, creating a dynamic spiritual tradition.

Yet throughout this highly diverse and many-faceted history, certain themes and characteristics keep recurring. This book tells the story of Jewish mysticism in chronological order, each chapter focusing on a particular time and place, a particular group of mystics, a particular movement in the ever-evolving story of Jewish mysticism. Roughly, the themes that keep reappearing, in spite of vast cultural and historic differences, can be grouped as follows: the chain of transmission, divine unity, divine language, inner journey and mystic experience, and the theme that suffuses all aspects of Jewish mysticism – Revelation and Concealment.

The chain of transmission

From the time of antiquity, before there were written records that

attest to an historical lineage of mystics, we encounter many legends

and traditions about the biblical patriarchs which portray them as

spiritual masters – evolved beings in contact with the divine who

imparted their sacred knowledge to humanity. For example, several

legends about Adam symbolically tell the story of God bestowing upon him

the spiritual teaching in the form of a book, or as a gemstone, which he

later passed down through the generations. Eventually, as the legends

explain, this knowledge, this light, was shared with humanity through

the prophetic mission of Moses and his spiritual heirs – the Israelite

prophets.

After the period of the Bible, we have more distinct evidence that mystics continued in their quest to have the experience of God. The merkavah (chariot) mystics, active from the first to eighth centuries, would assemble discreetly in small groups to undertake their spiritual journey and lend support to one another. They were called chariot mystics because their mystical experiences were portrayed as a journey in a chariot. Their teachings were brought to Europe by ancient travelers around the Mediterranean basin. They spread from Palestine and Babylonia to Italy, from there to Germany, and later to France, Spain, and throughout Europe.

In many of these documents there are references to heavenly revelations and contact with the prophet Elijah and other supernatural beings. Yet there was always an emphasis on the transmission of the teachings from master to disciple. Beginning in medieval times, the kabbalists passed on their teachings in secrecy, and later more openly. The relationship of these mystic masters with their disciples was very intimate. They would assemble in small groups called hevras, or idras, their entire lives being devoted to adhering to their masters’ instructions with great sincerity and intensity.

It is with Hasidism, the movement that began in eighteenth-century Poland, that the teachings were spread to the general populace, the householders – no longer remaining the province of an elite group of mystics. And in Hasidism we find the most explicit emphasis on the importance of the spiritual master, the tsadik. He is described as descending from his high rung on the ladder of spirituality to the low level of ordinary people, and raising them to his level where they might experience the divine bliss and joy. Sometimes the master himself was considered the ladder, whose lowest rung was on earth and whose highest was in heaven – he could straddle both the worlds. His consciousness was in the physical as well as the spiritual realms, and thus his true spiritual nature was concealed by his physical body. One of the Habad hasidim said that the tsadik was “infinite substance garbed in flesh and blood.”2 By attaching oneself to such a master, individuals could ascend to the heights of divine experience.

The theme of concealment and revelation may also be found in the belief that there are true spiritual masters present among humanity, but they are disguised as ordinary persons. The example of the prophet Moses is often brought forth: Moses is depicted as an ordinary, somewhat clumsy person with a stutter, yet God chose him for the divine mission of saving his people. In the medieval Zohar, the most important text of the Kabbalah, there are poignant tales of a mule driver who is wiser than the renowned rabbis, and of a child who is the hidden spiritual master. Numerous stories have also been recorded about the hidden spirituality of the first hasidic master, the Ba’al Shem Tov, who concealed himself as an uneducated ignoramus and, ultimately, through his actions and pronouncements, revealed that he was the great master and liberator of souls. So the true seeker needs to be watchful and thoughtful, as one never knows where or when he will find his master.

Perhaps these stories are also a metaphor for the deep truth that all of us, who seem to be quite ordinary, are created in the image of God – that we, as we are, contain the potential for the greatest heights of spiritual achievement. Our soul is a spark, a particle of the divine essence, trapped in the physical world only temporarily, as we await liberation through the teachers he sends.

Divine unity

An important characteristic of Jewish mysticism is that, despite the

expression of the religion through a multiplicity of outer forms and

rituals, there is a sense that a single spiritual reality abides in and

underlies everything. To the mystics, the one God, who is the object of

prayer and the focus of religious practice, can be realized through

meditation as the singular creative power that gives life to the entire

creation. Without it, creation would disintegrate.

The most important prayer in Jewish life is a quote from the Bible: “Hear O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One” (Deuteronomy 6:4). This oneness is taken by the mystics very literally. It is not just lip-service to a simplistic concept of “monotheism,” as taught to every school child in the Jewish world. The “one God” is the power, the divine presence that is experienced by the mystic as an abstract entity empowering everything, consciousness filling and encompassing the entire creation. And, from the practical human level, it allows one to accept that every event and condition of life, both pleasant and unpleasant, is an expression of the divine will, as there is nothing outside of God. As such, all of life is divine. As Samuel ben Kalonymus of Germany wrote in the twelfth century:

Everything is in You

and You are in everything

You fill everything and you encompass it all;

When everything was created,

You were in everything;

Before everything was created,

You were everything.3

The multiplicity of the material creation leads us to think that there truly is a diverse reality, but mystics know through personal experience that there is only one divine reality or substance flowing through all of creation. It is the only true reality, as the coarse outer covering of the material creation will perish in time, and only the divine truth or essence will remain. In contemporary terms one could call this a “nondual” approach to religion as it sees the one, rather than the many, in everything.

Kabbalist mystics in medieval times introduced the terms ayin (nothing) and yesh (substance) for these two opposites, ayin signifying the formless divine essence that pervades everything, and yesh the physical creation. The tension between the two poles also became the defining motif of Habad Hasidism in the nineteenth century, which emphasized the importance of looking beyond the revealed realm of yesh to come in touch with ayin – the concealed infinite.

From approximately the twelfth century, Jewish mystics developed a complex symbolism describing the spiritual realms and the process of creation. The literature describing this symbolism makes up the bulk of the texts of the Kabbalah. At its core was the need to explain how yesh – matter – could have been created by a God who is ayin – entirely abstract and without substance. The kabbalists taught that a series of divine qualities (midot) were emanated from the supreme God. These qualities were also called emanations (sefirot), and were generally visualized as flowing in a hierarchical order, each sefirah (emanation) a projection or reflection of the one above but existing at a lower vibratory level. Thus the light, the power, of the unitary Godhead, also called the Ayn-Sof (the infinite eternal, from the word ayin), which is beyond differentiation, flows downward through the sefirot, subtly dividing into positive and negative poles. Said another way, the primal divine light breaks apart, its sparks becoming separated from their source, imprisoned in the material creation. This is the realm of duality.

The symbolism of the sefirot was extended by each generation of mystics to interpretations of the narratives and personalities of the Hebrew Bible, each being identified with a particular sefirah. Thus the biblical stories were understood not simply as tales of human beings interacting with one another and with God, but also as metaphors for the relationship between the qualities of the divine and God himself, and as an allegory of the events of Jewish history.

With the contribution of numerous mystics following the spiritual path over hundreds of years, the symbolism of the Kabbalah has evolved into an elaborate interlinking set of symbols and metaphors with layer upon layer of meaning. Symbolism became the means of conveying several levels of reality at once. Each symbol is like a hypertext link to a multi-faceted reality concealed within a simple word or phrase.

Divine language

From the very beginning, Jewish mystics were engaged in meditation on

the “name” or “word” of God, as this divine power or spirit was most

often called in the Bible. Over and over we read that the prophets came

in contact with this name or word, which gave them the experience of the

ruah ha-kodesh (the holy spirit). They attest to being uplifted

and enveloped by this power. And through their devotion to it, they had

the courage to bring God’s message to the Israelites of antiquity – to

seek God within themselves and act towards each other lovingly and

morally. The prophets often stressed this type of personal spirituality

over the performance of sacrifices the people were accustomed to.

After the biblical period, calling on God’s “name” became something different, as the concept of the “name” was transformed from being a power, an unspoken ineffable essence, an expression of the holy spirit, into a spoken or written word. From the time of the merkavah mystics in late antiquity, throughout the entire history of Jewish spirituality, mystics have used a variety of “outer” name practices to attain spiritual experience. Their devotion to these practices resulted in an intense level of concentration which allowed their minds and souls to become free of the mundane concerns of the material realm and attain a consciousness of the presence of God.

Often the mystics would take particular names or passages from the Torah (the first five books of the Bible) and deconstruct them, creating more and more complex “names” of God that have no literal meaning, which they would repeat numerous times. By repeating these meaningless syllables, the mind would no longer focus on meanings; it could attach itself to the letters of the words as abstract symbols and, they believed, rise above the intellectual activity of the mind.

An underlying motivation of the mystics in interpreting and using the text of the Bible in their meditations came from the belief that its very language carries a divine significance. Mystics believed that God had uttered the entire Torah and thus it is an expression of his holiness, his will, his being. They mined the Torah to find the deeper, sacred meaning that lay concealed in its text. This approach was called pardes. The word pardes in Hebrew means “orchard,” and on one level it is used literally for the mythical Garden of Eden; it gives us the word “paradise” – a metaphor for the garden of perfection – a place, or time, of idealized eternal life. But the letters PRDS are also used as an acronym in Hebrew – signifying four levels at which one can understand the Bible: Pshat (simple, literal meaning), Remez (hint, inference based on the literal), Drash (allegorical interpretation), and Sod (hidden, secret, mystical). This meaning of PRDS gives us an insight into the techniques that the Jewish mystics and sages used in interpreting the Torah. So the Torah finally became an esoteric text, its literal meaning concealing and providing a hint to its inner, secret meaning.

This approach informs the way the Jewish mystics have viewed all events and circumstances of life, both on an individual and communal level: every situation or historical event was understood as concealing an inner, hidden, mystical meaning with which it corresponded.

Inner journey and mystical experience

The rich mystical literature of Judaism describes journeys to realms

of higher consciousness, spiritual realms where God and his qualities

(or angels) are experienced. Some metaphors were used consistently in

different periods for this process, such as the ascent to a mountaintop.

When the Bible says that the prophet Moses ascended Mount Sinai to

receive the revelation of God, it implies a spiritual ascent as well as

a physical climb up a mountain. Similarly, the prophet Isaiah urges the

congregation of Israel to join him in the ascent to the mountaintop. The

Jewish mystics recognized this dual level of meaning. Abraham Abulafia,

a thirteenth-century mystic, wrote that there are two levels to

understanding the ascent up Mount Sinai: the physical or revealed, and

the spiritual or hidden. He writes:

The ascent to the mountain is an allusion to spiritual ascent – that is, to prophecy, for Moses ascended to the mountain, and he also ascended to the divine level. That ascent is combined with a revealed matter, and with a matter which is hidden; the revealed is the ascent of the mountain, and the hidden is the level of prophecy.4

Other mystics used the image of a ladder to convey the spiritual ascent. The biblical patriarch Jacob saw, in his dream, a ladder stretching from earth to heaven and linking the two. Many centuries later, the hasidic mystics of eighteenth-century Poland wrote of the spiritual master himself as the ladder who straddles the physical and spiritual worlds. The master would descend from his heights in the supernal realms to the physical world in order to raise human consciousness to the divine. He would leave his high rung and descend to our lower rung in order to save us.

As mentioned earlier, another important metaphor for the inner ascent that recurs in various periods – from the biblical to the modern – is that of the chariot (merkavah). In the Bible, Enoch and Elijah are described as having ascended to the heavens in a fiery chariot while still alive. The prophet Ezekiel had a vision of a chariot made of the wings of angels and supernatural creatures ascending to the heavens, accompanied by transcendent lights, colors, and the rushing of otherworldly sounds. So the merkavah mystics of antiquity took their terminology from these biblical accounts and commonly wrote of traveling to spiritual realms in the chariot of the body, eventually reaching the throne region of God – the body-chariot itself becoming transformed into the throne, signifying that each human being can be viewed as the throne of God, the place where God resides.

Some scholars attribute the mystics’ experiences to states of heightened imagination, or visions they had of ascending to the supernal realms. However, increasingly many students of Jewish mysticism are recognizing that these were meditative experiences, in which they took their attention within themselves and ascended to the higher levels of consciousness. Elliot Wolfson, an important modern scholar, brings the testimony of Hai Gaon in the tenth century. He wrote that the merkavah mystic’s purpose was to take his consciousness “into the innermost recesses of his heart.”5 These early practitioners “did not ascend on high but rather in the chamber of their heart they saw and contemplated like a person who sees and contemplates something clearly with his eyes, and they heard and spoke with a seeing eye by means of the holy spirit.”6 Clearly, this means that the mystics penetrated within themselves to a higher state of consciousness where they had the mystic vision of the divine.

Meditative experiences of inner light and sound are also recorded by many mystics in Jewish history: The medieval Jewish Sufis in Egypt and Palestine wrote of the nur batin (inner light) which they saw in their meditation, which they called hitbodedut (self-isolation). Isaac of Akko, a kabbalist mystic of the thirteenth century, wrote of being in a state between sleep and awakening, and seeing “a very sweet and pleasing light. And this light was not like the light that comes from the sun, but it was like the light of day, the light of dawn just before the sun shines.” 7 Many other kabbalists attest to their experiences of light in meditation; some, like Abraham Abulafia in the thirteenth century, also wrote of hearing the inner sound. The experiences of these past mystics hint at a variety of practices through which they entered the hidden realms of spirituality. While their practices may have differed at different times and places, the record of their experiences points toward the universal reality they discovered beyond the physical olam – the ineffable revelation concealed within the realm of yesh.

Conclusion

Because Judaism is a scripture-based religion, which emphasizes the

engagement of the intellect in spiritual practice, it had historically

been restricted to the elite and the male – women were forbidden to read

the scriptures or study Talmud. That is all changing, however. Parallel

to the growing acceptance of women as equal partners in Jewish religious

life, in the synagogue and the academy, there are many women scholars

doing important research about Jewish mystics of the past and teaching

meditation to contemporary seekers.

What is the appeal of Jewish mysticism, especially the Kabbalah, today in the twenty-first century? Perhaps its nonlinear and symbolic explanation of the creation and the relationship of the human with the divine resonates with deeper truths that have an eternal, timeless meaning. It is a call to enter territory uncharted by the mind and look at life in this world as one of many layers of reality. And perhaps there is a side of the human mind that still yearns for the power of myth to take it beyond the linear, the rational, and the predictable. It yearns to explore the spiritual core that links all humanity together in a common heritage of divine truth and unity.

We are at a crossroads in history, as many mystical manuscripts and books are being brought to light and translated for the first time. So the testimonies of mystics of the past are available to the contemporary seeker who is inspired to embark on his or her own path. As a result, this book can only be an interim study; new research is coming to light almost every day and it would be impossible to incorporate the latest discoveries. An example is the ground-breaking study by Eitan Fishbane about the kabbalist Isaac of Akko, titled As Light Becomes Dawn, published just as this work was in the final stages of editing. But books can only take us so far. The reader is encouraged to continue searching for the truth that is concealed within the revealed – and ultimately to go beyond reading to first-hand experience of the divine – to rise from the level of yesh to the fullness of ayin. The challenge of the search is to find what we are looking for: the experience of the eternal name or word of God, the ruah ha-kodesh. It is possible.

CLASSIC TEXTS OF JUDAISM

The Hebrew Bible

IN HEBREW, THE HOLY SCRIPTURES are called the Torah, which

literally means teaching or revelation. The Torah generally refers to

the Pentateuch – the five books of Moses – the scroll containing the

books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.* It is

generally accepted by scholars that the Torah as we know it today was

actually written by at least four authors between the ninth and sixth

centuries BCE, drawing on still older documents and even older oral

traditions. It was probably edited and combined into one scroll in the

fifth or fourth century BCE, at a time when the Israelites had

experienced exile and faced potential fragmentation as a people and were

in need of a sense of identity with a strong religious and national

focus.* The Greek names for each book are commonly used in all English

translations of the Bible, and so they are used herein. In Christianity,

the Hebrew Bible is often referred to as the Old Testament, but Jews do

not use this term as it implies that the Israelites’ covenant or

testament from God has been superseded by a newer testament or covenant.

Understandably, this is a sensitive issue.

Genesis tells the story of the beginnings of the creation and humanity: Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, Noah and the great Flood, the tower of Babel, an account of the lives of the patriarchs (Abraham, Isaac, Jacob), and the origins of the tribal clan of Israel. Genesis ends with Joseph, Jacob’s favorite son, being sold into slavery in Egypt by his brothers. Abraham is often dated to about 2500 BCE.

Exodus, the second book, concerns the sufferings of the Israelites as slaves in Egypt and the appearance of Moses as their savior. The mass exodus of the Israelites from Egypt, the early years of their wanderings in the desert, and the divine revelation of God’s will and teaching on Sinai, perhaps in 1400 BCE, are the main events of the book. The prose and poetry are powerful. The laws of the covenant between God and man, and the details of the building of the Tabernacle and evolution of the worship of YHWH make up the last third of the book.

It might strike some readers as odd that the name of God, often spelled as Jehovah or Yahweh, has been spelled as YHWH, without any vowels between the consonants. This is in deference to those Jews who believe that it is forbidden to pronounce the name of God because of its awe-inspiring power. They use only the consonants of the name as a way of referring to him and giving the sense that the name is unpronounceable.

Leviticus is a record of the priestly forms of worship. The renowned translator Everett Fox separates it into three sections: 1) the sacrificial, consisting of laws governing the various types of sacrifices required, 2) ritual pollution and purification, affecting the general population and the priests, and 3) the concepts and rules of holiness – sacred behavior, sacred time (the calendar), and sacred space. It is generally assumed that this section of the Bible was written by a priestly author or authors of the lineage of Aaron, Moses’ brother, who was the first high priest.

Numbers, the fourth book, continues with the narrative of the Israelites’ journey in the wilderness before reaching the “promised land” that God promised to them in the covenant as recounted in Exodus. There are various events demonstrating the rebellious nature of the Israelites. The book contains beautiful biblical poetry. Other sections explain the duties of the Levites, who assist the priests in the shrines, and give laws governing ritual purity and the priestly worship of YHWH. The last section gives instruction on the forthcoming invasion and conquest of Canaan.

The name Deuteronomy, of the fifth and final book, refers to the fact that it is a duplication of much of the earlier books. It is couched as a long narrative given by Moses to the Israelites before his death, impressing on them the importance of adherence to the covenant. It ends with Moses’ poignant farewell, as he died before entering the promised land, after naming Joshua as his successor.

It is generally accepted that Deuteronomy was written sometime in the seventh century bce and found in the Temple during the reign of King Josiah, who used it to justify a purge of the many syncretistic and pagan practices that had persisted in the Israelite worship of YHWH. Josiah had seen the exile of the northern kingdom of Israel to Assyria and wanted to avoid a similar conquest and exile.* Probably under the influence of the priests, and perhaps also influenced by prophets like Isaiah and Jeremiah, he attributed the conquest of Israel to its failure to adhere to the covenant. God’s love and compassion for his “chosen people” is expressed in the form of warnings that nonadherence to the covenant would bring suffering and doom.

The biblical books that follow Deuteronomy – Joshua, Judges, 1 and 2 Samuel, and 1 and 2 Kings – are all written in the same style as Deuteronomy, and it is generally accepted that they were written by the same person. Together they constitute a complete history, a seamless account, starting with the death of Moses, through the conquest of Canaan under Joshua, the period of the judges, the early united monarchy, the division into two kingdoms, and the conquest of the northern kingdom by Assyria. The history ends with the glorious reign of Josiah, followed by the exile of the southern kingdom to Babylon.

The final editing of all the strains of the Torah into one text was probably done in the fifth or fourth century BCE, at least 500 years after many of the events recounted would have taken place.8

The term Torah, although strictly speaking referring only to the five books discussed above, is often used for the entire Tanakh – which also includes the collections of the Nevi’im (Prophets) and Ketuvim (Writings). Together, these three collections make up the Jewish holy scriptures. The Prophets includes the books of Joshua, Judges, the two books of Samuel and Kings, and the life stories and writings of individual prophets like Amos, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and many others, who lived between the eleventh and fifth centuries BCE. In these books we find some of the most eloquent biblical poetry.

Since the nineteenth century, numerous scholars have painstakingly studied the prophets’ writings and have demonstrated that most of the sayings and proverbs, which are written in a poetic style, are authentic, while the narratives about their lives and historic events, written mostly in prose, are heavily mixed with the additions, commentaries, and interpolations of later editors. Joseph Blenkinsopp, a respected biblical scholar, lays out the current thinking on this subject: “The poetry in the prophetic books arose as a spontaneous expression of the prophet’s transformed consciousness, and could therefore serve as a reliable criterion for distinguishing genuine prophetic sayings from editorial additions and embellishments.”9 By focusing on the most authentic parts of the prophets’ teachings, we can get a fairly accurate picture of the nature of their spiritual leadership.

The Writings includes works commonly considered part of the Wisdom literature of the ancient Hebrews, such as Proverbs and Ecclesiastes. It presents the spiritually inspiring stories of Ruth, Daniel, and Job, the poetry of the Song of Songs and Lamentations, the historical books of Ezra and Nehemiah, and the two books of Chronicles. The Psalms, greatly valued by Jews, Christians, and Muslims equally, is one of the most important of these scrolls.

With the canonization of the Bible, many inspiring books written in the centuries after the Jews returned from exile and rebuilt their Temple became considered as “external” works, or “apocrypha.” Their study was initially forbidden to Jews, though nowadays they are available for all to appreciate.

Talmud and Midrash

After the fall of Jerusalem to the Romans in the year 70 CE, the

court and academy retreated to a town called Yavneh under the leadership

of Yohanan ben Zakkai. The title rabbi, which literally means

“my master” or “my teacher,” was first given by Yohanan to his disciples

in the year 75 CE, to confer upon them the status of authority. From the

second to sixth centuries the title was used for the group of sages who

acted as advisors, guides, and teachers to the ordinary people living in

Palestine and Babylonia who struggled to please God while coping with

everyday worries and problems.* These rabbis were the authors and editors

of the Mishnah, Gemara, and Midrash, the texts which became the

cornerstone of “rabbinic Judaism,” the mainstream religious orientation

of the Jews for the next twenty centuries.

The Mishnah (from the word shanah, meaning to repeat or study), is an orderly arrangement of the laws derived from the Bible; it is organized in sixty-three tractates according to six broad subjects covering agriculture, civil and criminal law, marriage, the Temple rites of worship, issues of purity, and so forth. Written mostly at Yavneh by the rabbis called the tanna’im (repeaters, teachers), it was completed in the year 215 CE. In the academies, the Mishnah was memorized by students who heard it from the tanna’im. A supplement with some items not included was called the Baraita, and was published shortly afterwards.

The Gemara (from the Aramaic gemar, meaning study or teaching), produced by subsequent generations of rabbis called the amora’im (interpreters), is the most comprehensive supplement to the Mishnah and is organized accordingly. Produced in two versions – the Jerusalem or Palestinian (completed in the early fifth century) and the more-lengthy Babylonian (completed about a century later), it presents detailed discussions concerning all the legal issues which were of interest to the two sister academies of rabbis in Palestine and Babylonia. Together, the Mishnah and Gemara are referred to as the Talmud. In addition to the legal orientation of the Talmud, there are anecdotes about the rabbis which give hints to their spiritual and mystical activities and teachings.

A highly unusual and atypical chapter of the Mishnah is called Pirkei Avot, “Ethics of the Fathers.” It presents anecdotes about the sages and spiritual masters from the Maccabean period (second century BCE) through the mishnaic time. The authors of the Pirkei Avot present themselves as the heirs to a sacred chain of spirituality they believed began with God’s self-revelation to Moses. They see the entire prophetic period through the lens of their own rabbinic form of leadership, and even refer to Moses as “Moses our rabbi.” Although this is recognized as myth, it still points to the wide acceptance of the concept of a divinely appointed or mandated spiritual leadership being active in every generation.

The Midrash is the earliest literary form of supplementary Torah and uses the method of deductive reasoning to interpret the Bible. Written by anonymous rabbis and collected in the early second century, it follows the order of the chapters of the Bible, and includes both halakhah (the legal parts of the text) and aggadah or haggadah (the nonlegal parts – legends and anecdotes which reveal moral or spiritual principles). It became a model for many works of Jewish mysticism in later centuries. Mystical texts of later periods, such as those of the merkavah (chariot) mystics and the Kabbalah, are introduced in the appropriate chapters.

Editions used

Unless otherwise mentioned, Bible citations are taken from the

Tanach: The Holy Scriptures in The CD-ROM Judaic Classics Library, published by the

Institute for Computers in Jewish Life and Davka Corporation, Chicago,

IL, 1991–96. Bible translation is also partially based on The

Jerusalem Bible, Koren Publishers. Koren Bible citations are

indicated as KB following the citation. In a few instances, I have

retranslated a term when necessary to bring out its meaning more

clearly. The Tanach CD-ROM mentioned above also includes:

The Soncino Talmud, The Soncino Midrash Rabbah, The Soncino

Zohar. Most citations from Talmud, Midrash, and Zohar are drawn

from this translation.

TRANSLITERATION GUIDE

In the interest of avoiding diacritical marks, a simplified approach to transliteration of certain Hebrew sounds and letters has been taken:

The guttural ח (khet) sound is rendered as h, and in this book is not differentiated from the normal aspirated h sound.

The כ (khaf) is rendered as kh

The צ (tsadi) is rendered as ts

The ת (tav) is rendered as t

In Hebrew, plural forms of nouns end either in the masculine im, as in hasid – hasidim (devotee – devotees), or in the feminine ot, as in sefirah – sefirot (emanation – emanations). In many places it was preferable to keep the Hebrew plural forms rather than trying to convert them into English.

Hebrew nouns and verbs may have the prefix ha- or he- attached (meaning “the”), or ve- meaning “and.”

EDITORIAL NOTE

In order to facilitate ease of reading, certain stylistic decisions have been made:

Most Hebrew words have been italicized wherever they appear in the book. However, those which appear very frequently have only been italicized when they are introduced or if the words themselves are being discussed from a linguistic or philological perspective.

A short form has been used for the sources in the Endnotes and Footnotes. Full citations are given in the Bibliography.

CHAPTER 1

In the Beginning...

SPIRITUAL MASTERSHIP IN JUDAISM can be traced to the beginning of time – with the stories of Adam, Enoch, Noah, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, Moses, and other legendary figures whose lives are captured in the first five books of the Hebrew Bible. In subsequent books of the Bible, in the collections called the Prophets and Writings, the narrative continues with the teachings of prophets like Elijah, Samuel, Amos, Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel. The hereditary priests also played a role in providing spiritual guidance through the Temple ritual in which the Israelites attempted to commune with the divine.*

Of the earliest biblical figures – probably up until the time of Moses – we have to rely on the stories and legends collected in the midrashim (rabbinic commentaries on the Bible), the narrative texts of the Talmud, the mystical interpretations of the Zohar (the primary work of the medieval Kabbalah), and other material. We don’t have straightforward narratives in the Bible itself describing the mystic experiences of these patriarchs – just hints here and there, which were expanded upon by the later literature. What is significant, however, is what this later literature focused on – the possibility of personal contact with the divine – the first-hand experience of the divine power, the ascent to higher spiritual realms. This demonstrates that there was always a subtext of personal spiritual experience and transmission embedded alongside the literal history that the Bible presented. The later mystics were able to extract these spiritual themes from the Bible’s narrative of the events of the men and women of an earlier time.

~•~

ADAM, THE FIRST MAN, the first human being: To Jewish mystics he became the archetype of humanity, whom they called Adam Kadmon (the primal Adam). They understood him symbolically as the macrocosm within whom all life was generated, like the Primordial Man of the Upanishads10 and the P’an ku (primal man) of China.11

The legends surrounding Adam are compelling. In addition to the well-known stories of Adam and Eve in Genesis, many legends were passed down from generation to generation in sources outside the Bible; some were written down as midrashim, or preserved in the Zohar and other collections. Some not included in the Jewish sources appear in the Muslim hadith (narrations originating from the words and deeds of Muhammad). Indeed, the very foundation of the Jewish religion is based on a literature conveying the experiences of evolved souls who had direct revelation from God, and the transmission of that spiritual knowledge, often secretly, from one generation to the other through a line of masters, beginning with Adam himself, the first man. This is not the Adam of original sin whom we know from the biblical story of the Garden of Eden, but the Adam of light – the one chosen by God to receive His light and transmit it to succeeding generations. These legends assume that Adam was given a divine mission to convey God’s spiritual light and wisdom to the world.

A fifth-century legend recounts that when Adam and Eve were banished from the Garden of Eden, they lost the primordial celestial light – the light that was God’s first creation. Later an angel returned a small fragment to them in the form of a gemstone, a tsohar.

Without this light, the world seemed dark to them, for the sun shone like a candle in comparison. But God preserved one small part of that precious light inside a glowing stone, and the angel Raziel delivered this stone to Adam after they had been expelled from the Garden of Eden as a token of the world they had left behind. This jewel, known as the tsohar, sometimes glowed and sometimes hid its light.12

At his death, the legend recounts, Adam entrusted the stone to his son Seth who used it to gain spiritual insight. Seth peered into it and became a great prophet. It was then passed down to Enoch, in the seventh generation after Adam, who also became spiritually awakened by virtue of it and eventually ascended to the heavens where he was transformed into an angel. About Enoch there are only a few lines in the Bible (Genesis 5:18–24) and yet a whole esoteric tradition grew around him; he is portrayed as a spiritual master who ascended to the heavens in mystic transport while still physically alive and saw God enthroned in all his glory, and then shared the divine teachings with his earthly descendants.

The story of the tsohar continues through the first generations of man and reveals how each person – Methusalah (Enoch’s son), Noah, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, and Moses – used the stone to come closer to God and gain spiritual insight.

The jewel symbolizes the primal divine wisdom, the spiritual knowledge, the inner light, that is the heritage of humanity. It is the link between man and God. The legend says that God had originally bestowed this divine light upon Adam. Adam lost touch with it when he was disobedient to God and listened to the voice of his ego which told him to eat the forbidden fruit. Even though Adam was banished from the Garden of Eden, God preserved this light for Adam and his successors, in the form of a gemstone that an angel later returned to Adam. This is a poetic way of saying that this wisdom still remains within the realm of human realization because God has kept it for us. That it is passed down through the generations, through a lineage of prophets and patriarchs, tells us that it is there for everyone at all times.

The Bible begins its account of the creation of man with the statement, “This is the book of the generations of Adam” (Genesis 5:1). The Zohar interpreted this passage symbolically to mean that this book is actually the spiritual wisdom that is passed down from Adam through the generations. This means that the human lineage beginning with Adam is a spiritual lineage. Enoch inherited the same “book of the generations of Adam” and it gave him the key to the mystery of the holy wisdom.

Rabbi Abba said, “An actual book was brought down to Adam, from which he discovered supernal wisdom. This book reached the sons of Elohim [God], who contemplate and know it.13 This book was brought down by the master of mysteries [the angel Raziel], preceded by three envoys.

When Adam departed the Garden of Eden he grasped that book, but as he was leaving it flew away from him to the gate. He prayed and cried before his Lord, and it was restored to him as before, so wisdom would not be forgotten by humanity and they would strive to know their Lord. Similarly we have learned: Enoch had a book – a book from the site of the book of the generations of Adam, mystery of wisdom – for he was taken from the Earth, as is written: He was no more, for God took him (Genesis 5:24). He is the Lad [the heavenly servant].…* All hidden treasures above were entrusted to him, and he transmits, carrying out the mission. A thousand keys were handed to him; he conveys one hundred blessings every day, wreathing wreaths for his Lord. The blessed Holy One took him from the world to serve Him, as is written: for God took him.14

Following Adam, the Bible tells the story of Noah and the great flood, in which God commanded Noah to build an ark in order to save one male and one female of each species. According to some students of ancient myth, the ark symbolizes the continuity of life, and thus the core of the spiritual teachings, through the cosmic cycles of creation, destruction, and re-creation.15 Noah functions as a mythical spiritual master, the archetypal savior of mankind, who carries the mystical teaching (symbolized as the potential for the continuity of life) from one age to another. In the Bible, Noah is called ish-tamim, a perfect or innocent man, tam meaning simple, whole, or perfect.

Noah is also called a tsadik, a term derived from tsedek (virtue, righteousness), a quality of God that human beings can emulate. Tsedek can also mean salvation, deliverance, or victory. Over the centuries, the tsadik was to become one of the most important terms for the spiritual master in Judaism.

Although the recorded legends about Adam, Noah, Enoch, and other personalities date from a much later period, they attest to the persistence of a genre of literature parallel to the Bible that presented these towering figures as spiritual adepts who had powerful mystical experiences through meditation and prayer – experiences so profound that they created a model for later Jewish mystics to emulate. They provided narratives through which the later mystics imparted their teachings.

Abraham

Abraham is regarded as the first spiritual father of the Jews,

because according to the story, he rejected idol worship and chose to

worship YHWH, the one God. The Bible gives an account of Abraham’s early

life and his journeys, at God’s command, from Ur in Mesopotamia, the

“land of his fathers,” to the land of Canaan. It tells of his devotion

to YHWH and of YHWH’s covenant with him. The covenant is a promise of

mutual faithfulness. It is a pledge between lovers, one divine and one

human. Abraham agrees that he will worship and devote himself to the one

Lord. In exchange, God promises his unceasing love and care for Abraham

and his descendants: that a great and mighty people would issue from

him, to whom He would bequeath a land “flowing with milk and honey,”

provided that they continued to be faithful to Him. The covenant was to

be sealed with the circumcision of male children issuing from Abraham

and his lineage. This is the story on a literal level.

But what does it mean to say that Abraham began to worship one God? From a mystical perspective, this worship of the one God, or monotheism as it is commonly called, is the worship of the unity that is God, the divine creative power or life force that permeates the entire creation; it is often referred to in the Bible as the essential, ineffable name or word of God, the holy spirit. Many of the ancient legends about Abraham reflect the esoteric tradition that he experienced God directly as the holy spirit (ruah ha-kodesh) and was given a divine mission to convey that knowledge to others.

Rabbi Judah Leib Alter of Ger (1847–1904), one of the most inspired of the later rabbis of Hasidism, taught about the deepest level of meaning of the prayer, “Hear O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One,” which is considered the embodiment of the monotheism taught by Abraham. He explains that the entire creation “is God himself.” God is the power immanent in the creation.

The proclamation of oneness that we declare each day in saying “Hear O Israel,” and so forth, needs to be understood as it truly is.… That which is entirely clear to me … based on the holy writings of great kabbalists, I am obligated to reveal to you … the meaning of “YHWH is One” is not that He is the only God, negating other gods (though this too is true!), but the meaning is deeper than that: there is no being other than Him. [This is true] even though it seems otherwise to most people … everything that exists in the world, spiritual and physical, is God himself.16

In a play on words, some of the rabbis of antiquity interpreted God’s command to Abraham to leave the home of his fathers and “go up” or “get thee forth” to the land that God would show him, as a command for Abraham to leave the lower level or state of consciousness that he normally inhabited and raise his consciousness to a spiritual level through meditation. The Hebrew says literally, “lekh lekha” – “go to yourself” (Genesis 12:1), which has been interpreted mystically as “go within yourself.”17 The rabbis believed that Abraham enjoyed communion with God through mystic experience.

Later Jewish mystics remarked that the covenant, which was marked by the rite of circumcision, was Abraham’s entry into a relationship with God’s “name.” The Zohar says that the covenant marks the time that Abraham became united with the higher wisdom, the “name” of God. The circumcision, which seals the covenant, symbolizes the cutting away of attachment to the lower levels, rungs, or grades of spirituality. In fact, the term brit milah, commonly translated as covenant of the circumcision, also means “covenant of the name.” The Zohar tells us that before entering into the covenant, Abraham had only seen God in a vision on particular occasions, but after that time he was always accompanied by God’s presence.

Previously God gave wisdom to Abraham to cleave to Him and to know the true meaning of faith, but only this lower grade actually spoke with him; but when he was circumcised, all the higher grades joined this lower grade to speak with him, and thus Abraham reached the summit of perfection. See now, before a man is circumcised he is not attached to the name of God, but when he is circumcised he enters into the name and is attached to it. Abram,* it is true, was attached to the name before he was circumcised, but not in the proper manner, but only through God’s extreme love for him; subsequently He commanded him to circumcise himself, and then he was vouchsafed the covenant which links all the supernal grades, a covenant of union which links the whole together so that every part is intertwined. Hence, till Abram was circumcised, God’s word with him was only in a vision, as has been said.18

The worship of the one God that Abraham taught to his descendants and disciples, therefore, was most probably an inner worship of the name of God, with which he had been united at the time of the covenant. This is the true monotheism – worship of the one divine principle that is everlasting and sustains all.

The contemporary scholar of Jewish mysticism, Arthur Green, explains the essence of monotheism in mystical terms: “In the beginning there was only One. There still is only One. That One has no name, no face, nothing at all by which it can be described. Without end or limit, containing all that will ever come to be in an absolute undifferentiated oneness.”19

There are many traditions concerning Abraham as a spiritual master, a teacher who brought the divine wisdom from the East – the place of his origin – to Canaan, where he shared it with whomever he would invite into his home. The Zohar presents one of the most interesting. It recounts that Abraham purified the inhabitants of the world with water – a symbolic reference to the inner water, the divine wisdom which flows from the spiritual realms to the human. He then planted a tree wherever he resided, and through this he gave shade to all who “embraced the blessed Holy One.” The tree is also a symbol for the spiritual teaching. God is explicitly likened to the life-giving tree.

Come and see: Wherever Abraham resided, he planted a tree; but nowhere did it sprout fittingly until he resided in the land of Canaan. Through that tree, he discovered who embraced the blessed Holy One and who embraced idolatry. Whoever embraced the blessed Holy One – the tree would spread its branches, covering his head, shading him nicely. Whoever embraced the aspect of idolatry – that tree would withdraw, its branches rising above. Then Abraham knew and warned him – not departing until he embraced faith. Whoever was pure the tree would welcome; whoever was impure it would not, so Abraham knew and purified them with water. Underneath that tree was a spring of water: if someone needed immediate immersion, water gushed toward him and the tree’s branches withdrew. Then Abraham knew he was impure, requiring immediate immersion.…

Come and see: When Adam sinned, he sinned with the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, inflicting death upon all inhabitants of the world. When Abraham appeared, he mended the world with another tree, the Tree of Life, proclaiming faith to all inhabitants of the world.20

Adam’s sin by eating of the tree of knowledge of good and evil is symbolically a reference to Adam’s entering the world of duality, while the tree of life that Abraham planted symbolizes the divine unity, which is the ultimate source of all life.

Moses: The archetypal prophet

Moses is thought to have lived in the thirteenth century BCE, with

the Exodus having taken place around 1230. The personality of Moses

dominates all discussion of spirituality from his time onward. He is

considered the quintessential Israelite prophet. Yet he was not a grand

personality nor was he even called a prophet in the Bible – simply a man

of God. The biblical portrayal is of a humble man who struggled to

fulfill his divine calling and minister to a rebellious people. It is

his example that became the standard according to which all the mystics

of later generations were viewed, and they often referred to Moses as

their spiritual ancestor. The eighteenth-century hasidic master, the

Ba’al Shem Tov, taught:

Just as Moses was the head of all of his generation … so it is with every generation. The leaders have sparks [within the flame of their souls] from our teacher Moses.21

The medieval Jewish Sufi, Obadyah Maimonides, grandson of the twelfth-century philosopher Moses Maimonides, in his book The Treatise of the Pool, considered Noah, Enoch, Abraham, and other early patriarchs as practicing mystics, recipients and transmitters of the spiritual wisdom. He describes them as “intercessors” on behalf of the people, through whom the divine Will reached humanity. But, he says, by the time of Moses this lineage of prophecy had ceased to be active. It was only Moses who revived it.

The individuals who attained this state were very scarce, as it is said, “I have seen the sons of Heaven, but they are few,”22 like a drop in the sea.… For thou wilt find in each era but a single individual, such as Noah in the generation of the Flood, his predecessor Methuselah, Enoch, Lemekh, Shem, Eber, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. After the patriarchs the bond [wusla] was severed and there was no intercessor [safi] until the birth of the most glorious of beings and the noblest of creatures, our master Moses, peace be upon him, who restored it, through the Divine Will.23

This spiritual inheritance that Moses received from the earliest patriarchs and used on behalf of the Israelites is explained symbolically in another legend recounted in a medieval prayer book. The spiritual knowledge was symbolically “engraved” on a rod or staff that came from Adam, who handed it down to his son Seth; and it was passed along through the generations till Moses received it. As a rod or branch cut from the “tree of life,” it symbolizes the spiritual power, the divine “name” of God that Moses invoked as prophet and spiritual master of the Israelites. It is the rod with which he split the Red Sea, in the story of the Israelites fleeing slavery in Egypt.

There was nothing like it [the rod] in the world, for on it was engraved the ineffable name of God. This rod Adam handed on to Seth, and it was handed on from one generation to the next until Jacob, our father, went down to Egypt and handed it on to Joseph. Now, when Joseph died Pharaoh’s servants searched through everything in his house, and they deposited the rod in Pharaoh’s treasury.

In Pharaoh’s household was Jethro, the father-in-law of Moses; Jethro was one of Pharaoh’s astrologers and he learned of the importance of this rod by means of astrology. He took it and planted it in his garden, and it took root in the earth. By means of astrology Jethro discovered that whoever would be able to uproot this rod would be the savior of Israel. He therefore used to put people to the test, and when Moses came to his household and then rose and uprooted it, Jethro threw him into the dungeon he had in his courtyard. Zippora fell in love with Moses and demanded from her father that he be given her as husband. Thereupon Jethro married her off to Moses.24

This legend points to Moses as a true spiritual adept, inheritor of the divine wisdom passed down from the beginning.

But outside of tradition, what do we actually know about Moses? What was the nature of his spiritual revelation, and what was his relationship with his disciples, the Israelites? In other words, what were the characteristics that defined Moses as a prophet, a man sent by God to liberate the people? One important factor was the nature of his selection through a revelation of God in a “burning bush.” Second, is the extraordinary divine encounter he had on Mount Sinai and his continuing intimate communion and conversation with God throughout his entire prophetic career. Also of great importance was his humility, embodied in his reluctant acceptance of his mission.

SELECTION

The book of Exodus of the Bible recounts that Moses was tending the

sheep of Jethro, the Midianite priest and astrologer, when he had his

first prophetic experience – a direct encounter with the divine reality,

the “angel of the Lord,” manifested in a burning bush whose fire was

never consumed.

And the angel of the Lord appeared to him

in a flame of fire out of the midst of a bush;

And he looked, and, behold, the bush burned with fire,

and the bush was not consumed.And Moses said, I will now turn aside,

and see this great sight, why the bush is not burnt.

And when the Lord saw that he turned aside to see,

God called to him out of the midst of the bush,

and said, Moses, Moses.

And he said, Here am I.

Exodus 3:2–5

The passage suggests that suddenly, spontaneously, without warning, Moses was chosen by God to be the savior of the Israelites, freeing them from enslavement in Egypt. The idea of God making himself known to the prophet through a burning bush has galvanized the imaginations of generations of Bible readers, who have understood it literally. But it also seems to suggest a symbolic interpretation, as an ascent to a higher plane of consciousness in which Moses had a strong experience of the divine presence, manifested as the ineffable spiritual light and sound.

Moses’ response to this calling was indicative of his great humility. He said:

O my Lord, I am not eloquent,

neither yesterday nor the day before,

nor since you have spoken to your servant;

But I am slow of speech, and of a slow tongue.

And the Lord said to him,

Who has made man’s mouth?

Who makes the dumb, or deaf, or the seeing, or the blind?

Is it not I the Lord?

Now therefore go, and I will be with your mouth,

and teach you what you shall say.

Exodus 4:10–12

Moses did not seek out this role for himself – quite the opposite, he saw himself as unworthy, unable to speak. When he begged God to relieve him of this awesome responsibility, God reprimanded him for his lack of faith, saying that the One who has created the mouth, and the words it utters, would teach him what to say. What greater reassurance could he have needed? And yet he continued protesting, five times in all, until finally God allowed him to bring along his brother, Aaron, as a spokesman. The humility that marks this incident became identified with the character of Moses.

REVELATION

The Hebrew name for Egypt, Mitsrayim, literally means

constricted, and the sages interpreted the Israelites’ enslavement in

Egypt symbolically as signifying a state of spiritual constriction, a

lower spiritual state.25 Eventually, under the guidance of Moses, the

souls of the Israelites came in touch with true divinity, God’s word or

speech, through the revelation at Sinai.

The Israelites waited at the foot of the mountain while Moses communed with God at the mountaintop. There God revealed the Ten Commandments and, according to tradition, the entire Torah. The bestowal of the Ten Commandments symbolizes a renewal of God’s covenant with Abraham six hundred years before the revelation to Moses.

While Moses was intimately communing with the divine reality on their behalf, the Bible recounts that the Israelites were indulging in immoral behavior at the foot of the mountain, where they created and worshipped a golden calf. Although they were undeserving, the revelation was still bestowed on them. It was their spiritual heritage despite their ingratitude. This would be the model of their relationship with God during their forty years of wandering through the desert before reaching the “promised land.” The journey through the desert was to give them the opportunity to leave the constricted spiritual state they had come from and provide a transition to their growing spiritual awareness. But they consistently lost faith and acted rebellious, wanting to turn back to Egypt, and again and again God, through Moses, proved his love for them. This story is also a metaphor for the Israelites’ relationship with God and his prophets throughout their history – and for the soul’s infidelity and ingratitude to its spiritual heritage.

Moses’ experience of the awesome divine presence on the mountaintop is described dramatically in Exodus:

And Moses went up into the mount, and the cloud covered the mount. And the glory [kavod]* of the Lord abode upon Mount Sinai, and the cloud covered it six days; and the seventh day he called unto Moses from the midst of the cloud. And the sight of the glory of the Lord was like devouring fire on the top of the mount in the eyes of the children of Israel. And Moses went into the midst of the cloud, and went up into the mount; and Moses was in the mount forty days and forty nights.

EXODUS 24:15–18

How did the people perceive Moses after his experience?

And it came to pass, when Moses came down from Mount Sinai with the two tablets of Testimony in Moses’ hand, when he came down from the mount, that Moses knew not that the skin of his face shone while He [God] talked with him. And when Aaron and all the children of Israel saw Moses, behold, the skin of his face shone; and they were afraid to come closer to him. And Moses called to them; and Aaron and all the rulers of the congregation returned to him; and Moses talked to them. And afterward all the children of Israel came near, and he gave them in commandment all that the Lord had spoken with him in Mount Sinai. And when Moses had finished speaking with them, he put a veil on his face. But when Moses went in before the Lord to speak with him, he took the veil off, until he came out. And he came out, and spoke to the people of Israel that which he was commanded. And the children of Israel saw the face of Moses, that the skin of Moses’ face shone; and Moses put the veil upon his face again, until he went in to speak with him.

EXODUS 34:29–35

When Moses descended from the mountain with the Ten Commandments, his face shone with light – he had experienced within himself, in a state of higher consciousness, the spiritual light of God’s presence with which he glowed. The Israelites were frightened of the brilliance emanating from Moses – the immediate evidence of the power of the divine. He therefore put a veil over his face so that his light would not overwhelm them – this may be referring not so much to a physical veil but to his spiritually masking his spiritual brilliance so that he would not intimidate them. Moses sacrificed himself by standing between the Lord and the people as mediator, because the full presence of God’s self-revelation was too intense for them. The book of Deuteronomy recounts the people’s reaction to the divine revelation through fire and the awesome voice that projects from the fire. They were afraid they would die if they faced God directly, while Moses was able to speak with him and live.

The Lord talked with you face to face in the mount out of the midst of the fire, I stood between the Lord and you at that time, to tell you the word of the Lord; for you were afraid because of the fire, and went not up into the mount.… [He then repeats the Ten Commandments which were engraved on the Tablets, and then Moses says to them:] These words the Lord spoke to all your assembly in the mount out of the midst of the fire, of the cloud, and of the thick darkness, with a great voice which was not heard again. And he wrote them in two tablets of stone, and delivered them to me. And it came to pass, when you heard the voice out of the midst of the darkness, for the mountain burned with fire, that you came near me, all the heads of your tribes, and your elders; And you said, Behold, the Lord our God has shown us his glory and his greatness, and we have heard his voice out of the midst of the fire; we have seen this day that God talks with man, and he lives. Now therefore why should we die? for this great fire will consume us; if we hear the voice of the Lord our God any more, then we shall die.

DEUTEROMY 5:4–6, 19–22

The Bible also points to the high degree of Moses’ spiritual attainment by calling it a relationship where God spoke to him “mouth to mouth” and allowed him to see His “form”:

My servant Moses … is the trusted one in all my house. With him I speak mouth to mouth, manifestly, and not in dark speech; and he beholds the form of the Lord.

NUMBERS 12:7–8

Many Jewish mystics have taught that Moses’ prophetic experience of the revelation of the Torah on the mountaintop was a metaphor for his spiritual ascent, in which he experienced, first hand, the divine power – the essential or unwritten, ineffable Torah or divine word. According to Abraham Abulafia, a thirteenth-century kabbalist, “the ascent to the mountain is an allusion to spiritual ascent – that is, to prophecy.” He writes:

For Moses ascended to the mountain, and he also ascended to the divine level. That ascent is combined with a revealed matter, and with a matter which is hidden; the revealed [matter] is the ascent of the mountain, and the hidden [aspect] is the level of prophecy.26

Arthur Green asks us to think about the fundamental significance of revelation. He understands Moses’ encounter with the divine realm on a mystical level:

What then do we mean by revelation? Whether we understand the tale of Sinai as a historic event or as a metaphor for the collective religious experience of Israel, we have to ask this question. Here, too, the notion of primordial Torah is the key. Revelation does not necessarily refer to the giving of a truth that we did not possess previously. On the contrary, the primary meaning of revelation means that our eyes are now opened, we are able to see that which had been true all along but was hidden from us.… The truth that God underlies reality, and always has, now becomes completely apparent.…

What is it that is revealed at Sinai? Revelation is the self-disclosure of God. Hitgallut, the Hebrew term for “revelation,” is in the reflexive mode, meaning that the gift of Sinai is the gift of God’s own self. God has nothing but God to reveal to us.… The “good news” of Sinai is all there in God’s “I am.”27

Moses explicitly urged the Israelites to look within themselves to find God, “in your own mouth and own heart”:

For this commandment which I command you this day, is not hidden from you, nor is it far off. It is not in heaven, that you should say, Who shall go up for us to heaven, and bring it to us, that we may hear it, and do it? Nor is it beyond the sea, that you should say, Who shall go over the sea for us, and bring it to us, that we may hear it, and do it? But the word is very near to you, in your mouth, and in your heart, that you may do it.

DEUTERONOMY 30:11–14