Download | Print | Archives

November 2012

Saints are Tender of Heart

The Loving Master

The Eighteen Qualities of a Buddha

The wisdom of Buddhist texts provides an inspiring description of some attributes of a true Master …

There Are No Failures in Sant Mat

Talking About Time

Hot and Cold

Don’t we all wonder at times if we are the only ones who blow hot and cold on this path? …

Something to Think About

Little Children

Suffer the little children to come unto me … for of such is the kingdom of God …

Grandmother’s Table

The God Gene Theory

Heart

If

Worry is one of the most debilitating habits of mind …

Diamond Mines and Chimney Sweeps

A Master at Work

The T Factor

Feeling Funny

The Fruit of Hurry

Book Review

The Grace in Dying: How We Are Transformed Spiritually as We Die …

Start scrolling the issue:

Saints are Tender of Heart

Soft and tender are saints,

no one else in the world is like them.

There is no one else like them;

they are kind and merciful to all.

Foe and friend are alike to them,

and alike are bad luck and good fortune.

They are tender as flowers;

not even in a dream do they see others’ faults.

They ever wish well to others,

for they savour the wine of divine love.

Affable to all, with a gentle smile,

soft and sweet of speech are they.

Cheerful whatever happens, they emanate coolness;

in every glance they radiate compassion.

Whatever one might say to them, O Paltu,

they are not in the least perturbed.

Soft and tender like saints, no one else in the world is like them.

Saint Paltu

The Loving Master

As we grow as disciples on this spiritual path, we begin to know our Satguru to be a loving companion, someone we can relate to on a personal level. The Master remains ever eager to build a one-to-one relationship with us through his Shabd form. By travelling intensively and giving satsangs, interviews and seva meetings he takes every opportunity to make us feel wanted and special.

For outward contacts there are limitations upon us as well as the Master, but inwardly the care he has for us makes the love and efforts of the most devoted mother in the world pale into insignificance. The Master’s concern for us is unquestionable and, despite our rebellious nature, he feels only an overwhelming compassion toward us. In Legacy of Love, Maharaj Charan Singh makes a profound observation:

You don’t fall in love with the Master; Master has fallen in love with us. And then, we become restless – we feel we have fallen in love with him. The pull is from within.

This is no accident. Saints are an earthly manifestation of the Supreme Lord, whose essence has been described as love. The saints are wholly immersed in the ocean of love – brimful with it. Whenever they speak, nothing but love and loving words pour out. During the long ministry of Hazur Maharaj Ji, spanning nearly forty years, none of us can say that he ever appeared upset with us or reprimanded us with harsh words, though we may have fully deserved it. Equally, our experience with our present beloved Baba Ji is no different. The same relationship of intense love and forgiveness continues.

At a spiritual level, the Master is with every one of his disciples and that is entirely sufficient for him to protect us and take us back home. So why do the Masters travel so extensively? It is purely in response to our needs that they undertake such hardships. Man can only learn to love and create bonds through outward interaction with physical forms. This is why we cannot love God directly, since we cannot perceive him or relate to him through the sense organs. As the Master is keenly aware of the needs and limitations of his spiritual children and as he is a most devoted mother and father combined, he never tires of making us feel loved.

These engaging encounters with the physical Master are an invitation for us to meet him where he is waiting for us in his Radiant Form, at the eye centre. He wants us to reach this point at the earliest opportunity so that the proof of his abiding love may be made manifest to us. Then true love is aroused and faith in the Master becomes unshakeable.

Although most of us do attempt to meditate, generally we tend to lack focus, stamina and regularity in our spiritual endeavours. But regardless of the pitfalls, daily meditation is our way of saying to him “we love you for loving us.” Hazur Maharaj Ji often said that if the mind does not take to meditation, then sit as a matter of duty. The Master welcomes our futile attempts and the resulting failures in the same way that loving parents delight in seeing their child struggling to take his first step unaided. We know and appreciate that no relationship in the world flourishes without a conscious effort. At a practical level, daily meditation is no more than making a conscious effort at this all important relationship with the Master.

Everyone is seeking some peace and happiness in a strife-torn life. Above all we want to love and be loved. Since the love of the Master transcends every other love, it is infinitely worthwhile to receive his gift of love by putting all our energy into meditation. This greater love, a precious gift from the gracious Master, in turn brings a sense of peace and harmony that had previously eluded us due to our excessive preoccupation with material forms. The transformation is brought about naturally through the glory of the Shabd ringing within us. The Radiant Form of the Master beckons to us in all its glory. Great and joyful is the journey, made all the more attractive by the constant presence of the Shabd Master.

Our Father is love and we are small drops from that ocean of love. This huge machinery of the universe is worked on the eternal principle of love. So try to bring yourself in harmony with this principle of love. The deeper the love for the Master takes root in you, the fainter will be the worldly love in you. His love will displace the love of earthly things. Then the mind and spirit will transcend the flesh and the curtains will rise before you, one by one. The dark mysteries of the universe will become revealed to you and you will find yourself in the loving lap of the holy Father; in fact, you will be one with him.

Maharaj Sawan Singh, The Dawn of Light

The Eighteen Qualities of a Buddha

The wisdom of Buddhist texts provides an inspiring description of some attributes of a true Master.

According to Buddhist texts, a Buddha possesses eighteen qualities expressing his perfection. Six are associated with his outer behaviour: he moves gracefully and his physical conduct is never founded upon delusion of any kind; his speech is neither garrulous, loud, or ill-considered; he possesses an unfailing memory and intelligence; he is always at peace; he is free of conceptual thinking, not clinging to ideas; he is diligent in all matters, free from indifference or carelessness.

Six qualities are associated with his inner, spiritual realization: he gives unwavering attention to his work of spreading the message of the dharma for the benefit of all beings; he is indefatigable, never losing his energy and vigour; he is always focused, mindful, and aware, seeing things for exactly what they are; he has unfailing wisdom, discernment, and understanding; he lives in a state of constant meditation; and he is permanently liberated.

Six qualities are associated with his state of consciousness and permanent meditative awareness: his deeds, his speech, and his mind are all informed and permeated by his state of constant meditation; as a consequence, whatever he does, says or thinks is meaningful. Likewise, his all-pervading awareness gives him an unobscured vision and wisdom concerning the past, the present, and the future; as a consequence, he knows everything.

Taken from Garma Chang, Buddhist Teaching of Totality; Khenpo Chöga, Drops of Nectar (Vol. 1); Ratnagotra-vibhaga tr. Jikido Takasaki

There Are No Failures in Sant Mat

It was a Saturday satsang in Delhi, where Baba Ji speaks for fifteen minutes after the Hindi satsang. Sitting close to the TV monitor, one could see his face alive, his eyes alert and his expression serious. And then he spoke about how we remain chained within concepts, we don’t put the teaching into practice. He told us to live spirituality, to walk the path. And there was an urgency when he questioned why we had come to Sant Mat if not to give time to meditation? I felt that he was anxious and concerned.

After the satsang, my companion said Baba Ji appeared to be chiding us for not doing our duty. Suddenly, I realized that many a time I also face a similar predicament. I teach in a university. I keep telling the students to work hard, to keep their goal in mind and not to waste their time in watching TV and other purposeless activities. They also don’t listen. I keep repeating the advice ad nauseam, but they don’t bother. If they miss classes, I worry about their attendance; if they don’t submit their assignments I keep reminding them of the approaching deadline. At times I feel exasperated at their indifference. In fact, I realize, I am more concerned and anxious about them than they are about themselves.

And at the end of the year, when some of them fail, I feel bad. I tell them I saw it coming, they were given enough warnings but they didn’t bother. I commiserate with them and then leave them with the advice to work hard the next time. I move forward to the next class, to a fresh batch of students, leaving the old ones behind.

But, in Sant Mat, there are no failures, nobody is left behind. The Master, our teacher, doesn’t have the luxury of leaving us behind.

He has to make us succeed. When I thought about it, I could barely imagine the onerous task he has at hand. If we don’t do our meditation and don’t connect, he doesn’t say sorry and turn away. We are given the warning that once we are attached to a bulldozer, it is better to walk, otherwise we will be dragged. However, he doesn’t want to drag us. He tries harder than we do to make us succeed. He keeps repeating that if we take one step, he will take a hundred to meet us.

As parents, consider how far we go with our children. How much unhappiness do our children give us? They don’t listen to us, they do all the things we feel are inappropriate, be it their eating habits, their lifestyle, their casual indifference to things we feel are very important in life. They are our flesh and blood – we are willing to go to any extent to help them. For their sake we break so many rules, even transgress morally and socially to make them happy. Yet, a point comes when we feel so exasperated that we give up. We say “enough is enough”. We let them go their way. We accept defeat and express our helplessness when we say, “Okay, let them do what they want, let them face the consequences”. We give up.

But a Master can’t give up, he won’t give up even though we behave like irresponsible children. We must remember that he is not helpless, he can easily teach us a lesson; but he is full of love and forgiveness -very patient, very generous, merciful and indulgent – much more than we are towards our own children. His task is enormous. He has to carry the burden of all failures, a burden that is increasing by the day, yet he can’t give up.

I could now understand the concern and anxiety on Baba Ji’s face. I felt so small, so humbled, I wanted to find a place to hide myself. I realized not only the greatness and the generosity of the Master, but also the heavy burden – our burden – that he has to carry on his shoulders.

Do his shoulders stoop? No, not at all, but our relentless onslaught is perhaps enough to make them stoop. Have we come to Sant Mat to give him all this trouble? We need to think. If our all-loving and all-forgiving Master appears unhappy at our lackadaisical attitude towards meditation, if he is displeased when we turn our face away from him, this should be a matter of deep concern for us.

It should be our earnest endeavour to please the Master. In a question and answer session (quoted in the January 2010 issue of Spiritual Link) someone asked him, “Master, do you love me?” His answer was very simple yet profound. He said that love is a two-way street. In other words, love cannot be one-sided. The Master cannot walk alone on the path of love with no reciprocation. Effort has to be made by both the parties – the lover and the beloved – for love to succeed. Our lack of effort will weaken our relationship.

Baba Ji also made a startling and most unexpected statement: he said that he needs us as much as we need him, that the Master worships the Lord through his disciples. This idea appears wonderful and awe-inspiring at the same time. He also needs us? It suggests that our responsibility is as great as his. Are we fulfilling our responsibility? Are we, in any way, reciprocating his grace, love, kindness and generosity? He doesn’t let us fail. Should we fail him? If we don’t want to fail him then shouldn’t we do something about it, right now?

Let our relationship become a fruitful partnership. Let us fulfil our responsibility, let us reciprocate, let us give a little of the love back to him. Let’s meditate. Let’s just do it.

Talking About Time

In the discourse ‘Come my Friend to Your True Home,’ Maharaj Charan Singh makes a clear statement which we might find disconcerting: “With the passage of time, whatever happiness we experience will inevitably be transformed into pain.”

This is then qualified by the Master as he goes on to explain that the passage of time also ensures that no one remains unrelievedly unhappy in this world. The fact is that our life stories, or karmas, work themselves out through the medium of time and we are caught in that constantly changing flood like logs of wood floating down a river:

Imagine the currents in a river. The movement of one brings several pieces of wood together, while the movement of another disperses them. Similarly, a wave of karma arises and within moments all our relationships are established: brothers, sisters, sons, daughters, friends and acquaintances. Another wave of karma comes and they all scatter, all in their own particular directions. Similarly, if we travel daily by train, we encounter many different passengers. They all get down when they reach their destinations, and when we reach our station we also disembark. Actually, we have no connection or relationship with any of them.

Maharaj Charan Singh, Spiritual Discourses, Vol.II

When unhappy situations resolve themselves, we are grateful for the passage of time, but when our days with someone we love are over, we are broken-hearted. In Buddhism, Path to Nirvana, the author makes the point that it was when Prince Siddhartha really awoke to our vulnerability to time and change that he was prompted to look for an escape:

It is recounted that it was the sight of old age, suffering, disease and death that turned Prince Siddhartha away from the pleasures of the world towards the path of enlightenment. Witnessing each of these common phenomena only once was enough for the highly pure and perceptive prince to be estranged from life’s transitory and perishable nature, and he at once made a firm determination to search for the state beyond change, decay and destruction – the state of deathlessness.

Although our human life is rare, invaluable, and endowed with immense potential, it is short and fragile.

K. N. Upadhyaya, Buddhism, Path to Nirvana, A Perspective

In a letter in Spiritual Gems, Maharaj Sawan Singh, writing in the middle of the twentieth century, explains time in its widest context:

All that has been created is bound to change and decay. There is dissolution of earth, planets, sun, and stars, but at very long intervals – too long for human conception. Who can say when this present planetary system was created? Prophets, yogis, and astronomers give their estimates, and the latter revise their estimates with every new discovery, but who can say how often this dissolution has been repeated? Only he who creates, knows it. Suffice it to say that for human beings sitting outside the eye centre, the time is infinitely long since the creation came into being and when it will disappear again. So there is nothing to worry about the next war or the atom bomb; this very kind of loose, vague talk was indulged in during and at the end of the Great War, and is also indulged in after floods, earthquakes, famines and plagues. The worry should be about the entry into the eye centre and meeting the Radiant Form of the Master, so that the Master is made a companion on whom reliance can be placed here and hereafter. He who has been connected with the Word cannot go amiss in catastrophe or peace. He has a place to go to and goes there, and is not lost.

He reassures the disciple, who must have written to him in a state of anxiety, by reminding him that the disciple of a true Master “has a place to go and goes there, and is not lost.”

As expressed in Buddhism, Path to Nirvana, “our human life is … endowed with immense potential” in that within this transient environment, whoever has been initiated by a true Master has been given the means to go beyond time. The writer continues:

We have the choice to uncover, develop and utilize this potential and thereby attain immortality, the very goal of this life; or to disregard, degrade and misuse it and thereby remain caught in the cycle of birth and death, wasting this life. Thus, we can go up or down, rise or fall, by using or misusing this life. Buddhism therefore emphasizes the need to be vigilant and to make sincere efforts to attain immortality and liberation, thereby fulfilling the highest possibilities of this human life.

Indicating the importance of vigilance and right effort in pursuing the path of the pure Dharma that leads to immortality, the Buddha says:

The life of a single day of a person

Who exerts himself to see the immortal state

Is better than the life of a hundred years of him

Who does not exert himself …

It is most comprehensively summed up by Maharaj Jagat Singh who writes as follows in this beautiful and memorable passage from one of his letters published in The Science of the Soul:

Time changes and will go on changing, but Nam does not change. The current of Nam goes on as usual. It is Nam which changes the times and brings about all changes. Till we are able to put our consciousness in Nam, we will be subject to changes, now happy and now miserable. That is why the saints repeatedly exhort us to withdraw our conscious attention from the nine doors of the body and fix it in Shabd. As we do this and our attention is withdrawn from the body and enjoys the bliss of Nam, we develop power of endurance and spiritual depth. After crossing the perishable states of Maya, we enter the eternal state of Nam and, freed from the cycle of births and deaths, are entitled to everlasting happiness.

Hot and Cold

Don’t we all wonder at times if we are the only ones who blow hot and cold on this path? There are days when we come together with other satsangis and feel tremendous warmth – as if in each other’s company our need for higher love is somehow expressed. Rather than a remote ideal, Master comes back into focus as a friend, an exciting companion. But there are other days when guilt is our constant reminder of a duty we are failing to carry out, and then we feel a heavy burden in our hearts. How often we seem to swing from one extreme to another. But if the dark moments are painful, how sweet is the coming back into the light.

The friendship of the Master, his initiation, is no little gift, but often its value seems too subtle for our worldly demands. With astonishing regularity we look for satisfaction in all the wrong places. But there is no peace in that route, and it only increases our longing for the lightness and joy of his company. Master once said that it is a hard fact of life that the Shabd, the spirit, is our only true friend. But sometimes we need a push in the right direction and events have to test us to our limits before we are willing to see the truth.

When we are in trouble, we naturally look for solace inside. Indeed, sometimes desperation inspires us to look deeper inside ourselves than we have ever looked before. But, in fact, anything that helps us to actively focus within is beneficial; is bringing us closer to the point of contact. And as our consciousness ventures beyond the familiar, it becomes more alive than ever, then the miracle of life really begins. In Die to Live, Maharaj Charan Singh talks about this awakening:

Q: Maharaj Ji, I know the disciple must struggle to learn to develop the proper love for the Master. Can you speak of the nature of the Master’s love for the disciple?

A: Master’s love for the disciple? The disciple only thinks he loves the Master. Actually it’s the Master who creates that love in him. We only think we worship the Father. Actually, he is the one who is pulling us from within to make us worship him.

Q: Master, if we have no love and we have no devotion and we have no desire to meditate, how do we come to the Master?

A: If we had no devotion, no desire for meditation, we would not have come to the path at all. The one who has pulled us to the path will also give us those things. He has not forgotten us after pulling us to the path. He is still there within us.

Perhaps meditation is just the dying of our old selves to experience the subtle, intangible spirit within. Through the five holy names and the focusing of our thoughts on higher love, we definitely can find peace.

We should try to imagine for a minute how it might look to God. Picture him watching us, struggling in utter darkness, surrounded by uncertainty and temptation, but nevertheless somehow remaining steadfast in our search for light. Would this not move him? Surely, the holy spirit, the source of all love, the cause and object of our search, will not be able to resist our fragile attempts to make contact for too long. Our effort, empty though it may seem to us at the time, is in reality an act of courage and love – and perhaps the more hopeless the experience seems to the disciple, the greater its value, if he persists.

If we have a dozen reasons to hesitate, we still need to proceed. What choice do we have? We are miserable if we remain as we are, and all our efforts to mitigate our pain constantly fail. Surely keeping our rebellious natures still at the eye centre for meditation is only a slight discomfort compared to some of the other things we go through? Better to stop running away from the facts. There is only one move left for us to make: to centre our minds and focus our attention inward on our real friend.

Why should we worry? The order has already been given: a wave of mercy and spiritual uplift, more powerful than we can imagine, has already been set in motion. Just a little effort on our part is required for us to be moved by it; to realize and relish it, for it to be able to loosen our roots so that we can be freed by its liberating force.

If meditation is a blind leap of faith, it is blind only until the inner darkness is stirred with his presence, until the radiance can no longer be questioned. The Master’s nature is love. He is insisting that we join him inside. Perhaps even at this moment, he is longing for us more than we can imagine. So why hesitate? Who could refuse such an invitation?

The Father is always with you. You live, move and have your being in him. He is always helping you in every kind of task that you perform. The nearer you come to him, the more fully you will feel his presence and realize his help. As love for him increases in you, you will get a deeper and deeper realization of his Radiant Form within yourself. But you must remember that you should not expect spiritual realization all at once.

Maharaj Sawan Singh, The Dawn of Light

Something to Think About

Knowledge

Knowledge acquired through learning, and knowledge as a gift from God, are as different and as far apart as earth from heaven. Knowledge from God is like the light of the sun; knowledge through learning is merely the dull reflection of that light. Knowledge from God is like raging fire; knowledge through learning is like a spark from that fire.

Robert Van de Wever, Rumi in a Nutshell

But how does it profit a man if he gets full knowledge of all the planets and yet does not know what is within himself? Which is better, the knowledge of the universe, or the love of God? One does not become a greater soul by knowing the answers to all the questions regarding the universe. Real greatness lies in having the full knowledge of the Great One.

Maharaj Charan Singh, Quest for Light

People acquire knowledge of all kinds but remain ignorant of their soul, which is not only the basis of all knowledge, but the life that activates the body, mind and intellect. Real ignorance comes from not knowing one’s own self. Christ says in the Bible:

For what is a man profited, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?

Maharaj Sawan Singh, My Submission

Little Children

Suffer the little children to come unto me … for of such is the kingdom of God.

Jesus Christ’s words from the King James Bible are so well known because they convey a profound truth. The mere fact of being a child is not, of course, an indication of virtue, yet it’s easy to see some qualities in childhood that are full of grace.

A place apart

Under a tree, beneath a hedge, behind a piece of furniture, young children love to make their own private spaces, their den where the demands of the outside world cease. When we remember our own childhood games or observe small children in imaginative play, we see how they are able to periodically disconnect from the adult world and create their own environment, on their own terms, at least for a little while. What a great ability, and don’t we try to replicate this when we take time – not imaginatively but in concentration – to go into that special place within ourselves at the eye centre? Doing this sincerely and regularly, in the way we were shown at initiation, will help us to experience a greater sense of who we are and where we belong. In The Master Answers, Maharaj Charan Singh tells his initiates:

What do we mean by ‘inside’? When you close your eyes, you are automatically ‘inside’. Holding your attention within here, between the eyebrows, that is ‘inside’.… When you do not think about anything in the world, then you are here, in the centre behind the eyes.… Then naturally you start withdrawing upward and start seeing something inside.

The fact is, we carry a wonderful treasure inside ourselves. The Creator has placed his own spirit, the Shabd, within us and every human being can potentially come into conscious contact with the Shabd resounding in the forehead. It requires initiation from a spiritual adept, and then the firm resolve to set aside time each day to cultivate detachment from the ties of the world by withdrawing to the eye focus.

Letting go in play

Maharaj Charan Singh used to say that only attachment will create detachment. In other words, we will only let go, or detach from, the jumble of worldly thoughts which we hang on to and which in their turn hold us, when something more delightful has caught our attention. The mind’s addiction to endless thinking is actually a prison that prevents us from experiencing a greater reality. Beyond those prison bars we can find freedom in the soul’s attachment to the divine. Mirabai likened attachment to Shabd (discovering the fascination of God’s spirit within us) to playing with a wonderful toy:

I have obtained the rare toy of his Name;

O Rana, a precious toy have I found.Chiming sweetly it entered my body;

No hands ever gave it a form or shape.

Mira, The Divine Lover

Children instinctively know they need to play. Adults often forget how to do it – how to relax, to enjoy, find fun in joining all one’s attention to something. But we can actually discover a liberating delight in mentally turning over the five holy names in simran and then in reaching into the sound current.

The Masters have sometimes used the analogy of a child playing with its toys in a different way, to illustrate the mind’s absorption in the things of the world. They say when a child drops its toys and cries for its mother, she cannot resist it and comes forward to take her child in her arms. Similarly, when we turn aside from our obsessions here and look for the Lord, our father, he does not refuse us. In fact he has provided a far more wonderful ‘toy’ to occupy us, “the rare toy of his Name” as Mirabai calls the Shabd.

No calculation

Being a disciple isn’t just about sitting in meditation daily. After initiation we quickly find that the quality of our concentration depends to a large extent on how we interact with our fellow beings during the rest of our waking hours and how that interaction affects our mind. Do we try to be loving, unselfish, truthful, objective?

Baba Ji often advises us not to ‘calculate’. A bit of clear thinking and foresight may be useful in practical matters, but calculation has no part in love. The trouble is, inveigled by the negative qualities of the mind, sometimes described as the five passions, we are caught in the world and the world weighs everything in its own scales, attaching an arbitrary value to each thing: this thing is desirable, that is not; this work gives you wealth and status, that task is menial; this makes you popular, that may not. As adults we cannily adopt these standards (even if we don’t believe in them), hoping to do well for ourselves. Children on the other hand, know no such rules and therefore behave naturally. There is no calculation in a child beyond the little we teach him. He is as happy with pebbles as with diamonds. He loves sweeping the floor if he can do it alongside you. Love is his guide. If we could recapture some of this lost innocence it would make prioritizing meditation – not to mention adopting good, human values in daily living – so much simpler.

Trusting reliance

Another quality that we find in children is faith – and no wonder. Think of a newborn baby and its total dependence on the mother. The infant relies totally on the parents for food, warmth, nurture, protection. As he or she develops, all the information, all the skills needed for life, are passed on by those close to the child. In a loving environment the child will come to have absolute faith in “my mum”, “my dad”. But it will not last – not entirely! I wonder whether you remember the first time, maybe as a young teenager, that you realized that your parents might not be able to provide all life’s answers? And from then on, a certain mental separation from them evolved in you. Many of us eventually arrive at a place where we respect and love our parents but are also aware that they are limited beings like everyone else. And, in between, our mind will have wondered, assessed, challenged and questioned. We may rightly think that this is an inevitable part of growing up, but that doesn’t lessen the virtue of the younger child’s trust. A young child unquestioningly relies on his parents; mind does not come into the equation and there is perfect faith. Like this, a trusting reliance on God is a great asset for a spiritual seeker.

Reprogramming the mind

In the last example there is actually a big difference between reliance placed on fellow humans and the reliance we can place on our loving Creator. This is a Creator so concerned for his children that he sends his saints amongst us to gather us, support us and lead us home. The faith that a disciple gradually builds in his Master is never misplaced. Building faith is not an easy process because old habits mislead us and cloud the way we see things. But no matter how diffident we are, the Master remains our steadfast anchor.

The spiritual path taught by the Masters shows us that we can actually reprogram our mind and find again some of the simplicity and faith of the child. That’s what meditation is all about.

Maharaj Charan Singh says in Spiritual Perspectives, Vol. II:

With meditation our willpower becomes so strong that even if our mind has been wrongly conditioned and wrongly influenced in childhood, we can become a saint.

And in Volume I, he says:

Happiness doesn’t lie outside at all. It is a self-deception to think that I can be happy here, I can be happy there. If I have this, I’ll be happy. If I have that, I’ll be happy.… So unless we belong to the One to whom we really belong and who belongs to us, we can never be happy. And that One is the Father, the Lord.

So through our daily practice of meditation we are enabled to find that source of strength within us and gain the faith and confidence to be our own natural selves – spiritual beings, able to use our human birth wisely, trusting in God’s grace and moving steadily towards him.

A child belongs in its home, with its parents – that is her rightful place, where she is loved and secure. God is our Father and the soul’s place, as his child, is in his arms, blessed by his love.

Grandmother’s Table

Once there was a feeble old woman whose husband died and left her all alone, so she went to live with her son and his wife and their own little daughter. Every day the old woman’s sight dimmed and her hearing grew worse, and sometimes at dinner her hands trembled so badly the peas rolled off her spoon or the soup ran from her cup. The son and his wife could not help but be annoyed at the way she spilled her meal all over the table, and one day, after she knocked over a glass of milk, they told each other enough was enough.

They set up a small table for her next to the broom closet and made the old woman eat her meals there. She sat all alone, looking with tear-filled eyes across the room at the others. Sometimes they spoke to her while they ate, but usually it was to scold her for dropping a bowl or a fork.

One evening just before dinner, the little girl was busy playing on the floor with her building blocks, and her father asked her what she was making. “I’m building a little table for you and mother,” she smiled, “so you can eat by yourselves in the corner some day when I get big.”

Her parents sat staring at her for some time and then suddenly both began to cry. That night they led the old woman back to her place at the big table. From then on she ate with the rest of the family, and her son and his wife never seemed to mind a bit when she spilled something every now and then.

William J Bennett, The Book of Virtues

The God Gene Theory

We are told that we have been created as spiritual beings in a human body, and at first thought this may seem to be an uneasy association of opposites. But it can be seen to manifest itself in the search for faith in God and a divine plan, which is something that has occupied human minds in every civilisation and culture since the dawn of time – even without full understanding of what is being sought. The fact that the word ‘God’ is said to be the most Googled word on the Internet shows that this search for God as a concept is still universal today. This search is so widespread because it seems that knowledge of God is something of which we humans still have a dim memory; perhaps we once possessed it in a forgotten pre-existence. Rumi describes this memory very beautifully as celestial music, “the song of angels,” in his poem “Remembered Music”:

We, who are parts of Adam, heard with him

The song of angels and of seraphim.

Our memory, though dull and sad, retains

Some echo still of those unearthly strains

R.A. Nicholson, Rumi: Poet and Mystic

This spiritual inclination indicates that mankind believes that our all-knowing, all-loving Creator has not abandoned us and has surely provided us with some pathway, however obscure, to find him again. In his divine design he may have created the physical body just to be the vehicle required in which knowledge of him can be activated. In other words, spirituality may be wired into the physical neural circuitry of the whole human race so strongly that the gene for it has been favoured by natural selection to survive down the generations.

So is this distant memory of the knowledge of God hidden in our DNA? Does science have an answer to the mystery of the salvation of the soul? In his book, The God Gene: How Faith is Hardwired into our Genes, geneticist Dean Hamer says yes – he has been able to locate a genetic root for spirituality. In 1998, during the course of a personality trait survey for addiction, he measured a trait known as “self-transcendence,” which consisted of three other traits: self-forgetfulness or the ability to get lost in an experience; transpersonal identification or a feeling of connectedness to a larger universe, a feeling of oneness; and mysticism or openness to things not provable. All together they summed up a scale from feeling most to least spiritually inclined. Then, examining the genes of his subjects, he narrowed the field to nine specific genes and located a variation in one gene known as VMAT2, which directly related to the ability to feel self-transcendence, predisposing them towards spirituality and mystic experiences. He says that the God gene refers to the idea that human spirituality has an innate genetic component to it. It doesn’t mean that there’s one gene that makes people believe in God, but it refers to the fact that humans inherit a predisposition to be spiritual – to reach out and look for a higher being.

Dr Hamer asks: “What are the selective advantages of having God genes? Are they simply a side effect of the evolution of the mind, or do they offer us a more direct evolutionary advantage?” As well as regulating brain activity associated with mystic beliefs, one of the important roles that God genes play in natural selection is to provide human beings with an innate sense of optimism and well-being. Studies show that optimism seems to promote better health and quicker recovery from disease, prolonging life. He goes on to say: “There is now reasonable evidence that spirituality is in fact beneficial to our physical as well as mental health.” In other words, the fact that spirituality offers a physical advantage to the species ensures that the gene survives according to natural law.

Dr Hamer makes a strong distinction between spirituality and religion. The self-transcendence measure is heritable, maybe from past births, whereas religious beliefs have no genetic basis – observing rituals such as attending services are cultural and environmental and transferred by non-genetic means, as by imitation. Spirituality, on the other hand, is a state of mind; it is “innate – it comes from within, not from without”. Religions have tried to harness this innate spirituality in humans for institutional purposes but, in fact, God cannot be taught as part of religious dogma; he has to be experienced. This would seem to be Dr Hamer’s meaning when he writes: “We do not know God; we feel him.” That is, we do not know him intellectually, we experience him.

When the mind is focused, with love and devotion, in simran and bhajan, we are in meditation. But what is happening physically? Imaging systems have disclosed the chemical activity and blood flow in the brain connected with feelings during meditation. It is interesting to know that the technique used for concentration and self-forgetfulness activates the regions of the brain that are seen to light up in deep meditation. The deeper the meditation, the more active the frontal lobes of the brain become. These are the seat of concentration and attention. And as these light up, so another important region of the brain, the parietal lobe at the back, starts to dim. It is this lobe that orients us in time and space – boundaries of the self fall away creating the feeling of being at one with the universe. “The result is a radical shift in the communication between the front and the back of the brain – a shift that … brings a profound sense of joy, fulfilment and peace.”

The Creator may have hidden this spiritual gene in everyone’s DNA because his grace is available to all his children. He has programmed this God gene as a predisposition to spirituality, giving us all an open door. But the spiritual journey in the human body is more meaningful if it is left up to the individual’s effort to take that step to walk through the door into the unknown. For some it is not urgent and they are not ready to be interested, but for others there is a powerful pull to go through the open door. This is the spiritual being in us being drawn irresistibly by the exquisite sweetness of that remembered music of the spheres. Andrew Harvey quotes Rumi further in The Way of Passion:

How could the soul not take flight

When from the glorious presence

A soft call flows as sweet as honey, comes right up to her

And whispers, ‘Rise up now, come away.’

Dr Hamer says: “The existence of God genes is one more sign of the Creator’s ingenuity – a clever way to help us humans acknowledge and embrace his presence.” Embracing the divine presence is to hear and recognize the sound current, the creative force, that soft call as sweet as honey for the soul to return to its true home in the highest region. Rumi, in the same poem, uses an apt metaphor for the soul as a caged bird being irresistibly drawn to the freedom of the sky. He is saying that our Creator has not abandoned us here but is asking us to:

Fly away, fly away bird to your native home

You have leapt free of the cage

Your wings are flung back in the wind of God

Leave behind the stagnant and marshy waters

Hurry, hurry, hurry, O Bird, to the source of life.

Heart

In the physical body, the heart is the vital centre of physical functions, circulating nourishment to all the other organs. Interestingly, the heart is also a powerful symbol of emotion. In many contexts, when we use the word ‘heart’ we think of love. Love is one of the most worthwhile feelings we can experience. A heart full of love allows us to pass the time with peace and contentment. A loving heart is forgiving. No matter what happens around us, the loving heart will take all situations lightly and with understanding. It will even be able to appreciate negative happenings as a source of growth and be grateful for that.

But what if our heart actually feels full of pain, distrust, anguish or whatever the mind dumps there? Just as a physically impaired heart will disrupt the whole body, so a heart which is heavy and distressed in the emotional sense will affect our well-being in every way. The sensations that flow from such a heart will filter unease into every part of the body. The eye will see the worst in everyone and everything; the brain will produce negative thoughts and responses; the tongue will find good food unpalatable; the ear will crave to hear the scandals and shortcomings of others; the mouth will speak words of bitterness and falsehood and worst of all, a sick heart will even turn away from God’s love.

If we find ourselves in this state we know things are awry with us. So, if we feel bereft of love – estranged from others, from ourselves, and without love for the Master, what can we do?

The cure is the tried and tested remedy – simran and bhajan. In Philosophy of the Masters, Vol. I, Maharaj Sawan Singh writes:

When one is torn by cares and anxieties, when his body is diseased, when he is deeply immersed in domestic worries … even then, if he repeats the simran of the Lord, he shall attain inner calm and peace.

And if we are so fed up and downhearted that our mind refuses to say the holy words, what then? What can we do if we become too lazy to get out of bed and sit up for meditation, go to satsang or read a Sant Mat book? What do we do when we don’t even want to try to cure ourselves?

Actually every minute of the day, the Master’s holy energy is always with his initiates. Nothing and no one can disrupt this invincible force. In its own way and in its own time, our heart-sickness will disperse and we will find the strength to engage with simran again. Maharaj Charan Singh told us in Spiritual Perspectives, Vol. III:

On the path, we are always going ahead and ahead. But we have to pass through so many phases; so many human failings are there. But we ultimately overcome them. The Lord doesn’t commit any mistakes. If he has marked someone, he has got to pull him to his own level. We commit mistakes, but not the One who has marked us, who is pulling us from within.

He will infuse his love into us so that it reaches every cell; our brain will start with one positive thought which will lead to another and then another. As he helps us think positively, our heart starts on the road to healing itself and we understand Maharaj Charan Singh as he goes on to tells us:

You see, the Lord has given us so much in life, but we don’t have that thankful heart. Instead of asking the Father to give us the boons in life, we should ask him to give us that heart which is full of gratitude for what he has given us.

With this sense of gratitude, comes the knowledge: of course the Master loves me, he is love; he only knows how to love. He loves me and he loves everyone all the time, eternally, forever.

Then the joy starts, then the simran in all seriousness, then real meditation. This is how we experience his love; this is how we stay with his love, and this is how the heart stays healthy and open to enjoy this amazing encounter.

Whatever good or bad happens to you, through whatever person or object, directly proceeds from our loving Father. All persons and objects are but tools in his hand. If an evil befalls you, think it his greatest mercy. We have to suffer for our past actions sooner or later. Our Master, by taking us through these sufferings speedily, intends to relieve us of our burden earlier. And by this early payment of debt – because debt it is – the amount of the suffering is very much lessened. If we had to pay one ton at first, now we are released by paying one pound only.

Maharaj Sawan Singh, The Dawn of Light

If

Worry is one of the most debilitating habits of mind. Most of the things we worry about are hypothetical, but that doesn’t lessen their power to undermine our ability to keep faith in the Master and focus on meditation. Worry is a tyrant, so let’s take heart from the following story in which a brave people confronted another such tyrant with a brisk rebuff:

Long ago, the Spartans lived in the southern part of Greece in an area called Laconia; they were therefore sometimes called the Lacons. They were noted for their simple habits and their bravery; they were also known as a people who used few words and chose them carefully. Even today, a terse answer is often described as being ‘laconic’.

Philip of Macedon wanted to bring all Greece together under his rule and so embarked on a war against other states, including Sparta, which was one of the last to stand against him. Knowing that he must subdue the Spartans if he was to succeed, Philip brought his army to the borders of Laconia, and sent a message to the Spartans:

“You must submit at once,” he threatened them, “otherwise I will invade your country. And if I invade you will receive no mercy. If my army sallies forth it will pillage and burn everything you hold dear. If I march into Laconia, I will level your great city to the ground.”

The next day a messenger on horseback left Laconia and came across to Philip’s camp, bearing an important looking scroll. He was conducted to the general who had impatiently awaited this reply. When Philip opened the missive he found only one word written there.

That word was “IF”.

Diamond Mines and Chimney Sweeps

There is an old English expression which warns us about getting into situations which damage our tranquillity. It is ‘never wrestle with a chimney sweep’. This saying comes from a time when many households in the northern hemisphere were heated by coal and some houses had several chimneys. The sweep was a frequent visitor and always caused consternation, turmoil and anxiety in the house he was visiting. Nobody would ever shake his hand because they knew that the soot which clung to him would transfer itself to them. He represented the things which we know exist in the world – the dirt, the squalor, the complications we would do best to avoid.

As we live our lives as disciples we might remember this.

One example of complication is that we live in a world where choice seems to have become one of the ‘rights’ of civilized life. We have become used to having a whole range of options open to us for every possible aspect of living. These options can supposedly render our lives more enjoyable, less costly, increase our status or individuality; give us faster access to an ever increasing mass of ‘stuff’.

Once there was talking (varied by whispering or shouting). Then paper and pens made from sharpened sticks or quills. Now we have cell phones, iPads, texts, Skype, video, email, Twitter, and on and on, each with its tangled mass of tariffs and deals. Wasn’t talking (or shouting) so much less confusing?

How much of our physical and mental energy goes into worrying about how to make choices? How to do the research, how to decide, how to pay, which of the ever craftier deals to go for? If we don’t look out, this wrestling can cover us in more and more of the world’s soot.

Our great problem seems to be that we find the process seductive. We complain loudly about the nightmare of effort and time involved, but secretly get pleasure from our busy dealings – buying our gas from a supplier of nuclear energy or our water from a gas supplier!

We are here because our mind wills it. We ourselves weave the net of entanglement in which we live. The more dense and more complex the web, the less we are able to escape it. We are flies in a spider’s web. Enticed. Entangled. Wrapped in silk and sucked dry. The World Wide Web, the Internet, can be a useful tool but it shouldn’t take over our life.

Amongst this mad whirl of technology we must keep a grip on the basics of life, the simple absolutes: sun up, sun down; new moon, old moon; spring, summer; new life, old age. Death. And above all remember to focus on that greater absolute, that which fuels the whole creation, and which is sometimes called the Name of God.

This is the force, the power, the very essence of all existence. We choose to wrap around it so many layers of mind stuff – complete with that dusting of soot – making it vanish from our sight. That sooty spider’s web appears to us to be existence itself. But actually it’s the fabric that conceals the light within us. The light burns and shines in every cell of our being yet we are unaware of it and sit in darkness.

That desperate search for the latest gadget, the best deal, the biggest car or TV is part of what is keeping us from grasping the best deal of all, the simple touch of the Master’s finger.

Masters say that the lonely, needy souls are as visible as bonfires when viewed from the top of a mountain on a black night. Masters alone see who suffers from disenchantment with the world, those who know that deep within there is something brilliant, something of great value waiting to be extracted – diamonds within a mine. They draw these souls into their company and then begins the long process of digging through the covering layers and finding the jewel.

We cannot achieve this on our own. The Master alone has the power to do it. All we can do is please him and he will do the rest. How can we please him? By keeping to the instructions he gives us, most of which are simple and mechanical. He promises that even those that seem so difficult are easy if we really want to put them into practice. It can take a lifetime or it can take two minutes to let go of the world’s weight.

He tells us that one of the reasons it takes so long is that we try too hard. There is a well-known story about the monkey with its fist in a narrow-necked food jar. As long as it grasps the goodies in the jar, its hand is stuck and can’t be drawn out. Opening the fist should be easy enough: stretch the fingers, let things drop. But, like the monkey, we can’t; whilst we grasp the goodies (those deals and sticky ties of the world), we are prisoners. “Here’s a problem,” we tell ourselves. “If only I apply intellect to it, think it through, get some professional advice, I will be able to decide – which finger to loosen first, which next, why am I not succeeding?” But does it work?

Those souls who are drawn to the path are those inflicted with ‘divine discontent,’ those who have an inherent desire to look inwards and lean towards the light. This is the gift we must use if we are to please our Master. Fighting the intellect with the intellect, the mind with the mind, is not the answer. This is just feeding the mind’s love of creating problems, and then sitting down to worry over them.

Leaning inwards – doing simran – helps us to calm down, get things into perspective, stitch ourselves into the Master’s presence. He has the answers to all the problems. He either slides the answers we need imperceptibly into our minds or gives us the strength to glide over the difficulties without pain, not minding the results.

Leaning inwards is leaning towards what Maharaj Charan Singh called “the treasure within”. Luckily for us, reaching this treasure is not done by hard scrabble, but by doing nothing. Just sitting. We must not imagine though that ‘just sitting’ is as easy as ‘just doing nothing.’ The diamond that we seek may be waiting for us but it still needs effort to mine. It still needs us to apply discipline and exertion.

Although we cannot force our mind to let go, we can employ that effort towards a better discipleship which, together with proper time given to our meditation, will bit by bit increase the depth of concentration that we are able to achieve. To help our discipleship, the Master is the perfect exemplar of how to live in the world, and he provides a wealth of advice for us, not least in our literature which beautifully sets out the ideals we are working towards. Good human values and the wisdom of spiritual perspectives are encapsulated in the perfections that all Masters demonstrate to us in their daily lives. We cannot will the results of any effort we make but we can exert our will in how much we try to follow their example.

We can put our strength into putting the proper time into meditation. We can keep a fierce hold on our thoughts and our tongue, do simran, read books. In fact, we can do everything we can to hold on to the Master instead of the world.

If we want to get rich in soul and spirit, our task is to seek the diamond within. To sit in silence; do nothing; keep the face of the Master before us. This is so simple that most of us miss the point.

If, instead, we find the world and its playthings more alluring – well, we know where we’re likely to find ourselves: in a wrestling match with a chimney sweep.

A Master at Work

The following extracts from With the Three Masters, Vol.I, by Rai Sahib Munshi Ram, record daily life with Maharaj Sawan Singh:

8 to 14 October, 1942

While at his farm at Sikandapur, near Sirsa (District Hissar), the Master’s daily routine is as follows: After his morning breakfast at nine o’clock, he walks to his sugar factory, where the machines and equipment have been installed. This is located about two and a half miles from the house and is on the main Sirsa-Hissar road. There he supervises work until lunch time. Lunch for everybody arrives from the Sikandarpur House at about 1.30 p.m. Everybody is fed before the Master takes the food himself. After that he rests till five o’clock in the evening, while others get busy with their usual work. At six in the evening everyone returns to Sikandarpur House. The Master sits down on an easy chair in the open courtyard of the house. All the people sit around him and enjoy his physical presence and his precious utterances. After dinner, they all go to bed.…

The world has not derived so much benefit from the saints who renounce the world as it has from the saints who lead the life of a householder. The former have few connections with the world and its people. Except for their own body they have very little to care for and therefore the number of those who wait on them and attend to their various needs is comparatively small.

On the other hand, the saint who is a householder comes in contact with people from all walks of life – doctors, lawyers, teachers, merchants, relatives and friends as well as foes. Our Master has so greatly widened his circle of contacts that it must be a rare unfortunate satsangi who has had no opportunity to come into personal contact with him in some form or another and at one time or the other. He has several business matters awaiting his attention too, some of agricultural importance and others of legal importance. Besides there is a wide variety of persons he has to deal with ranging from the Commissioner of a Division, revenue officials, keepers of land records, doctors and school-teachers down to persons of the labour class like blacksmiths, carpenters, mechanics etc. There are other contacts arising out of the publication of books. People who do not understand the ways of the Masters object to the Master having such contacts. Those who are better informed, seeing in all this the Master’s great piety and benevolence, hold themselves speechless. Those blinded by ignorance feel that a person who is engrossed in worldly activities, even more than they are, cannot possibly be a real saint. Such people are doing a great wrong in attempting to form an opinion about the Master’s spiritual power and greatness on the basis of his worldly acts and deeds. The fact of the matter is that the human intellect is powerless to assess the spiritual merit of a saint. We may, however, begin to understand a little about these things, if we attend their discourses and live in their company for some time.

Maulana Rum, the great Persian saint, has dealt with this subject extremely well. He says, “You who are blind try not to judge us by looking at our life on the worldly plane. Beg for that eye from God with which you may be able to see that precious jewel that is shining within us.”

15 & 16 October, 1942

The Master was ready by five in the morning. We also got ready in time. We left Sikandarpur at five-thirty in the morning and, passing through Sirsa where the Master gave darshan to sangat, we arrived at Ludhiana in the evening where the Master held a satsang. A stranger asked a pertinent question, namely, when saints say that God is present within the human body, why then doesn’t he stop people from doing evil deeds? The Master replied that this question had been very ably answered by the great Indian saint Tulsidas in the preface to his Ramayana. The Master further stated: “There is fire in the wood, which is latent. If we rub one piece of wood against another, we are able to bring out this fire from the wood which then burns brightly. Similarly, if through meditation we realize God within us, he will certainly stop us from doing evil deeds.”

3 December, 1942

After returning to Dera [following a tour in November], the Master’s first evening discourse was on Swami Ji’s hymn “Repeat the Name of the Master” from Sar Bachan. I was translating the Master’s words to the foreigners who were present. The Master said that in the beginning meditation is like licking a tasteless block of stone, and that devotion to the Master does not become complete until the soul beholds the Radiant Form of the Master by crossing the sun and moon regions. Then the spiritual practice becomes facile and delightful because Shabd, the divine Word or sound current, is very sweet and captivating. One who has effaced himself by devotion to the Master, attains God-realization and freedom from the cycle of births and deaths.

The real benefactors are the saints who possess the key to the prison-house of this world. They throw open the gates of this vast prison-house with the key and tell the prisoners to get out and go to their true home. Other benefactors can give temporary relief to the prisoners, but they cannot grant them freedom by liberating them from the prison.

The T Factor

Life has become so busy for many satsangis that despite our best intentions, we are not seeing much action in terms of spiritual practice. Let’s say that, expressed as an equation, Intention (I) + Time (T) = Action (A). The problem for us is that the T factor has gone missing.

We all have heard about and practised time management in some phase of our lives. Many of us boast of being an effective time manager on our CVs!

But when it comes to the most important activity of our life, sadly, we fail to allocate enough time towards it. Deep down we all know that we can do it. The Master has said there are no failures in Sant Mat. So the very fact that he has accepted us and initiated us shows the immense trust he has in our capability. It’s his way of saying: “Yes, you can do it!”

Some of us may have heard the following story about setting priorities:

In his lecture to a group of business students, a professor in time management gave a classic example to explain a point. He pulled out a wide-mouthed jar and put some rocks in it, filling the jar to the top. He then asked the group whether the jar was full. The students unanimously replied that it was. He shook his head, took out a bucket of gravel and poured it into the jar. The gravel settled in between the rocks. He then asked the same question “Is the jar full?” The students were now getting the point and some of them replied, “No.” He was happy with the response, introduced a bucket of sand and repeated the action. The same question was asked again and they confidently replied that there was still space left in the jar. The professor then filled the jar to the brim with water.

What, the professor asked the group of students, was the purpose of the exercise? One of his students thought that the message was that if we work really hard, we can still fit more things in no matter how full our schedule.

The professor said that was not the point. He explained that the purpose behind it was to demonstrate that if we don’t put the big rocks in first, we will never be able to get them in at all.

When we reflect on this story and its meaning for us, we can think about what the big rocks of our own lives are and make sure that we put them first. In other words prioritize them in our schedules or daily routine.

We all need to strive to make meditation the biggest rock of our life. Remember, Master has often said that it’s our life support system. Once meditation tops the list of our priorities, everything else will fall into place automatically. Baba Ji has often said that if we do his work, he will do ours. That’s a reassurance from him that most of us tend to take too lightly.

The question, then, is what is stopping us? What prevents us from giving that hundred percent effort to please our Master? The Master often says that twenty-four hours in a day are more than enough for us to attend to our worldly and family obligations, as well as giving that much needed time to ourselves in meditation.

Perhaps we should think about who we actually are and what it is that we really need.

Do we honestly believe material wealth is going to make us feel happy and at peace within ourselves? Without a doubt, a certain amount of material wealth is needed to sustain oneself in this world but it’s entirely our decision where we want to draw the line. We’ve spent so many years trying to acquire one possession or the other. A thought to ponder upon is whether there has ever come a time when we decided, that’s it, I have everything I need to sustain myself in this world and need no more?

The fact is, our mind will never be satisfied with whatever we achieve materially. What we must focus on is our spiritual needs. We are actually spiritual beings going through a human experience, so it is fulfilment of our spiritual needs that will give us true happiness and peace.

Let’s not let the T factor come between us and our goal. There is always enough time – what’s missing is our determination.

Mind is a curious thing. It will gladly do all kinds of work externally without feeling tired, but the moment you put it to the spiritual exercises – ask it to sit still inside – it will try to escape by putting in all sorts of excuses, like the need for rest after a hard day’s work, need for rest because of a heavy stomach, bad weather and so forth. But if there is longing or if there is determination, then the inward progress will proceed uninterrupted. Those who complain of sleep at the time of meditation usually sit halfheartedly, only as a matter of routine, and not with any longing.

Maharaj Sawan Singh, The Dawn of Light

Feeling Funny

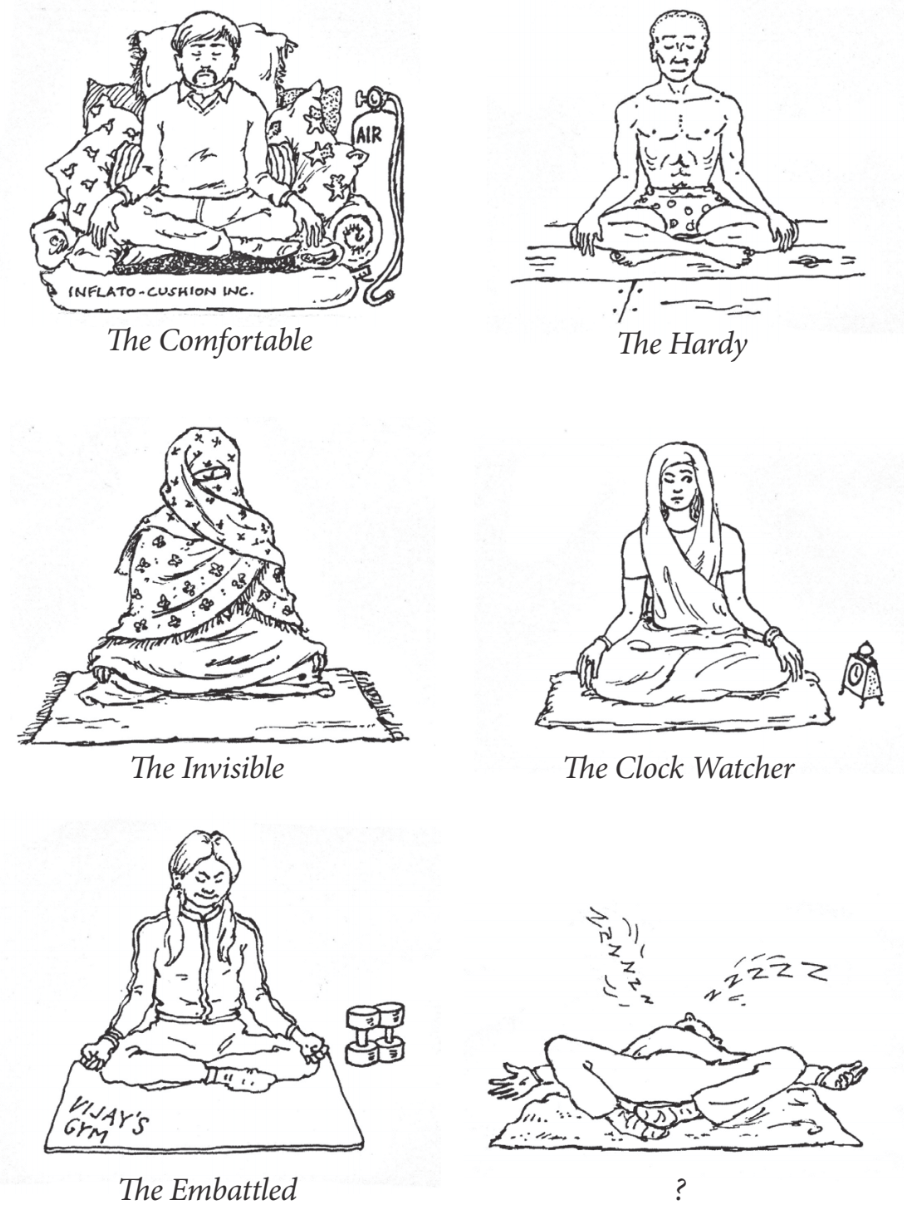

It Takes All Sorts

The Fruit of Hurry

It’s all too easy to fall into a tendency to hurry through the extraordinary experience of being a disciple. After all, don’t we hurry through so much of life? In our eagerness to ‘do well’ – in focusing on all kinds of desired and imagined results – we rush through the present moment. But by doing that, we actually undermine our progress.

We hurry when the ego over-exerts itself, full of its own ideas of what spirituality may entail. This may lead us to approach our own individuality as a curse that is to be overcome as quickly as possible. But that is not conducive to finding our ‘comfort level,’ and it certainly pushes up stress levels.

Overcoming the ego does not mean that we must deny what we are, however flawed. If we deny our reality, pretending to be, or rushing towards, something else, then we are building our spiritual life on shaky ground. Hurry breeds a surrogate, fickle faith and poorly hides this shaky foundation. It’s better to acknowledge our true condition and start from there.

Each of us has his or her own style and pace. Only when we consciously behold the Master inside and see nothing else do we go beyond our individuality. Until that time we should recognize our natural selves, find our balance, and seek to walk this spiritual path with appreciation and patience.

If you think about it, hurry comes with rigidity and dogmatism, with stagnation and standstill rather than progress. If we’re mentally at some other place, how can we listen properly to the Master? Unable to be fully alive to the present, we’ll doze off or drift away in satsang and remain very definitely in the power of the mind and the senses.

In daily life a sense of hurry may lead us to draw quick, superficial conclusions, to be judgemental and dismissive. This kind of hurrying often rubs off on others as well, when we persistently demand that they do as we do. In disregarding their right to go at their own pace, we may generate a negative reaction. The fruit of hurry has a bitter taste.

Why not make good use of the opportunity to turn every single day into a precious time by doing our simran, focused and wide awake? Regular and punctual bhajan and simran is the practical form of devotion or bhakti. We should do this spiritual seva with loving, faithful, and hence patient attention. Waiting at the eye centre is an opportunity, a gift of grace. The application of patience to meditation and to daily life is building a foundation for receiving God’s love. Walking the path slowly and steadily allows the mind to take one step at a time toward spiritual liberation.

Having once understood the direction we must face, we need not keep our eyes on the horizon but simply look to the present; the future will take care of itself. In a logical, unforced way, the point will eventually come when we realize our separation from the Supreme Being – that we are lone souls away from home – and surrender our individuality quite naturally. No bitter fruit for us then, as we taste at last the sweetness of the fruit of patient love.

Book Review

The Grace in Dying: How We Are Transformed Spiritually as We Die

By Kathleen Dowling Singh

Publisher: San Francisco: Harper, 1982.

ISBN: 0-06-251565-9

In this book, Kathleen Singh, a transpersonal psychologist and former hospice worker who has spent many hours with the dying, offers a spiritual and psychological explanation of the last stages of death, drawing on her studies of the world’s mystical and religious traditions.

Singh recounts many of her observations of ordinary people as they faced their final hour. She reports how, in the intense moments before death, some people expressed a perspective on life that echoes the major tenets of the world’s wisdom traditions. For many, she writes, “the time of dying can most certainly be a time of transformation, a time of moving from a sense of perceived tragedy to a sense of experienced grace,” accelerating “radical transformations leading the human being beyond the ego-bound self and its experience of separation and on into trans-personal, Unity consciousness that realizes its identity with the Ground of Being.” She quotes one dying woman: “I feel I am becoming part of something vast.”

Singh’s perspective on her experiences is shaped by her study of many wisdom traditions, among them Surat Shabd Yoga, Sufism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Christianity, Taoism, and Judaism. Drawing on this background, she elicits many parallels between the stages that lead up to physical death and the states of consciousness that a meditator passes through in order to “die while living”.

Singh focuses on cases of terminal illness where people have some time to comprehend the prognosis of death. Most of the cases she works with receive palliative care where

the death of the body is most often accompanied by less suffering than the death of the ego, the separate self. The suffering of the mental ego prior to entering the dying process is enormous. It is the suffering of the dismantling of the structure, the identity, the beliefs, the hopes, the dreams, the cherished memories, the fancied ‘proofs’ of the self.

She does not gloss over the terror, the hopelessness, or the physical pain that many people experience facing death. Rather, she finds that such conditions can sometimes serve as a crucible for the transformation of consciousness.

Singh has been hailed as “a second Kubler-Ross,” referring to the author who in 1969 identified the five stages of dying as denial, anger, bargaining, depression and finally acceptance. In Singh’s view, these stages are part of a lower level of consciousness that she calls Chaos, a stage that the dying person must go beyond to enter a stage of Surrender and finally Transcendence. For Singh, surrender means something more than just acceptance. One can accept “that which is” while still perceiving this reality as something separate from the self. In surrender, resistance at every level ceases as one willingly becomes active in “that which is”. Surrender does not mean giving up. In the words of Janet Quinn, a nurse:

Giving up is saying there’s nothing else to do…. To surrender is absolutely active and requires doing over and over again. Surrender is not something that is done once and for all. It’s required minute by minute. Being surrendered is becoming extraordinarily active in one’s process.… Surrender increases the quality of life … and the quality of one’s dying. There is a peacefulness that comes with that … versus the despair that comes with giving up.

Singh charts the development of the human being from birth through death in terms of states of consciousness. As the ego develops in the course of life, she says, it generates a series of dualisms, lines or boundaries limiting it and cordoning it off from the Ground of Being. She analyzes distinct levels of the mental ego, drawing on Gurdjieff ’s cartography of consciousness. In an ego-based state of consciousness, she points out, “We live, lost at the surface, in fear, attachment, anxiety and loneliness, motivated primarily by survival and control.” The approach of death dismantles all the masks of the ego, often triggering disillusionment, panic and despair. The artificial boundaries start to crumble and the narrow, hemmed-in self starts losing its limitations, she says, in the order in which it had constructed them.

Singh believes that death becomes transformative when we participate in it, instead of just enduring it.

As the body weakens and old illusions die, Spirit – that which is real and essential in each of us – emerges and the quality of living and participating in the present moment strengthens. We move ‘out of our own hands’, out of the anxious, grasping, calculating hands of our own separate identity, transported by grace – a power so much larger than the separate self – into safety, into peace.

As one nears death, one may learn that what is essential and real is, as Singh puts it, “the Holy”. What we hold most dear – our desires, attachments, fantasies, fears – is non-essential and unreal. “The Holy responds to none of this. It responds to what is real. The Holy demands that we return to it, with awareness, as pure light.”

At the approach of death we learn to sit and do nothing, and this can change the character of our perceptions. As a dying man whose world had become confined to the tiny window of his bedroom had put it, “All my life, I’ve been so busy … I don’t think I ever really saw blue before. I never saw green. Until now … How beautiful they are.” Another dying person said, “I’ve never been more fully alive.” This is a state beyond concepts, a state of experiencing the intrinsic value that exists in each act, thought and moment of connection.

Singh acknowledges, however, that such sudden leaps into higher levels of consciousness at the approach of physical death may be only temporary. As she puts it, “One experience in an expanded level of consciousness, no matter how profound and no matter how permanently embedded in consciousness, does not in and of itself raise the level of consciousness.” She theorizes about what such experiences portend for states of consciousness after death, questioning whether “the brief glimpse of Unity consciousness inherent in the experience of dying implies the guarantee of permanent residence in the Ground of Being.” Her own belief, based on the wisdom teachings she studies, is that consciousness does continue after death, and that one ought to prepare for that state throughout life. At the time of death there simply is not enough time to transcend the confusion and chaos that has already driven us through life and to take up “permanent residence” at higher states of consciousness.

Accordingly Singh is deeply interested in the practice of meditation, and devotes a chapter to it, entitled “Special Conditions of Transformation.” She describes meditation as the practice of willingly and completely “offering one’s self, one’s whole being, to the transformative process.” For her, the focused attention which one channelizes in meditation is nothing different from what is called “soul”. This control of attention through meditation simulates the experience of dying primarily by keeping the attention motionless in one spot, “the one seat.” She quotes Ken Wilber:

“Ultimately, a person in meditation [as in dying]… must face having no recourse at all. Having no recourse, no way out, no way forward or backward, he is reduced to the simplicity of the moment. His boundaries collapse and, as St Augustine put it, ‘he arrives at That which Is.”

In sum, Singh reports to us how many people experience powerful and uplifting grace in dying. In the words of a dying person, “I cannot tell you how beautiful this is,” or in the words of another, “I am turning into light.” Comparing such experiences to those experienced in meditation, Singh’s book inspires a practitioner of meditation to experience such states while living.

Book reviews express the opinions of the reviewers and not of the publisher.