Download | Print | Archives

July 2013

What This Love Is

Follow That Man

Just Give Yourself to Him

The battle cry of ‘never surrender’ has been heard throughout history …

Feeling Funny

Have Courage

Nelson Mandela once said that courage was not the absence of fear, but the triumph over it …

Already There

Sun at Midnight

In Tales of the Mystic East we find the following story …

Are You Sitting Comfortably?

I’ve been struggling with my meditation …

Give the Master a Chance

Turn Around - Listen

Turn around and listen to the great resonance of Shabd …

The Accommodation of Longing

Seeking Nam is a little like falling in love with someone of whom your family disapproves …

Keeping It Real

The Light of Understanding

Something to Think About

Book Review

Plotinus or the Simplicity of Vision …

Start scrolling the issue:

What This Love Is

What day is it?

It is every day,

My friend.

It is all of life,

My love.

We love each other and we live;

We live and we love each other.

And we do not know what this life is,

And we do not know what this day is,

And we do not know what this love is.

Jacques Prevert

Sometimes it seems that the only thing we know for certain about life is that we don’t know anything for certain. The world can be a confusing place; life is beset with difficulty, struggle, even tragedy. But we are the most fortunate of the fortunate, because through all this we have the Master’s hand to hold. We have his love. And if there is one certain thing in life, it is the love of a true friend.

The love of the Master is a truly precious gift - and yet how little we really appreciate it! As Jacques Prevert writes in his poem, “Song”: “We do not know what this love is”. But with steady application to our meditation, and submission to our Master, we can gradually come to know.

Slowly too we can learn to live in this day, this day that “is every day” - to live in this moment, as the present Master says. Through remembrance of the Lord and forgetfulness of our own ego, we can hope one day to truly let go, to give ourselves to the Master. And then perhaps we too will have learned not only what love is, but how to love.

Follow That Man

When we’re first initiated, it’s not uncommon to expect that within six months we’ll be sitting at the top of Trikuti overflowing with joy. However, ten or even twenty years later, we may find we’ve failed to rise much beyond the toes, never mind the eye centre. Untangling the karmic threads formed during the eons we have spent in this creation is a mighty task demanding courage and perseverance. Imagine sitting in front of a huge plate that contains a mountainous pile of spaghetti and being asked to unravel it thread by painstaking thread without tipping it off the plate.

Add to this seemingly impossible task the setbacks and hardships that life can bring, and it’s hardly surprising that many of us at some point throw our hands in the air and relegate meditation to something we do between going to work, taking care of the family, spending time with friends and relaxing in front of the TV or with a book.

But we’re missing the point. We might not yet be able to see the Master inside in all his radiant glory, yet each one of us already has at some level a personal understanding (based on our own experience) that he is certainly no ordinary human. And yet he is human too, and it is the very fact that he appears to us as much man as Master which enables us to connect with him and thus begin our spiritual journey.

And this is no ordinary journey on which he takes us. In the furious rush of this world, we face unrelenting exhortations to do things, to get stuff, to be someone - but in travelling this spiritual path, we’re asked simply to sit still and stop thinking.

This little injunction goes against everything the world stands for. We’ll gain little worldly respect for our endeavours in following this path, and may even be ridiculed. By and large, however, the world is simply indifferent, because Sant Mat is not the path of the world. The point here is that we can’t measure our progress on the path or our relationship with the Master in worldly terms.

He draws us from the dark shadows of our lives like a puppet master. We come to him frayed and suffering; in the orbit of his magnificent love we are soothed. A gentle burning takes place; the accumulated detritus of immeasurable time, the invisible layers of caked dirt and misery, are slowly cleaned away.

A steady stream of letting go

Perhaps we have some intuitive grasp of this when we see the Master. And maybe too we understand that for all our kicking and screaming we have no choice but to come to the Master, to this man who is so much more than a man, and follow him home. We gradually begin to understand that this path is but a steady stream of letting go, a gentle unfurling of our real nature, a release of the unnecessary burdens we carry. But it’s not an easy journey. In fact, at times it can be tremendously difficult, as the Master moulds us in the furnace of his love.

So if we’re disappointed that we haven’t attained what we had hoped when first initiated, or that meditation feels a hundred times more difficult than we expected, let us take heart that we are travelling not on a path of this world but on one that takes us out of this world. It’s not a journey we’re familiar with; we don’t know the wayposts or the distance to be travelled. But we can be certain that it is taking us towards our long-forgotten home. So it behooves us to carry on taking small steps forward, to continue fighting the mind, and to keep faith with our Master, who has come to guide us back.

Just Give Yourself to Him

The battle cry of ‘never surrender’ has been heard throughout history. It doesn’t come naturally to the ego to allow someone else to take us captive; our instinct is to fight for freedom. We are taught to hold on to our independence, and never give up. In worldly terms, surrender and freedom are opposing ideas.

But as with so many of our acquired beliefs, there are depths to this that the mind doesn’t immediately comprehend. Saints explain that rather than being opposites, surrender and freedom are two sides of the same coin; and they say that spiritual surrender - inner surrender -will bring us true freedom. In Spiritual Letters, Baba Jaimal Singh writes:

So long as the disciple does not take out the self by surrendering his all to the Satguru and removing himself from everything, he will not be liberated. So surrender your self and step aside…. Consider that each and every thing in the world - body, mind and wealth - belongs to the Satguru, that you are nothing.

This liberation from self is our spiritual goal, but surrendering our all is not so easy for the mind to accept. Saints know well the self-absorbed intransigence of the mind, and Maharaj Charan Singh tells us in Divine Light:

We never try to tell the mind that it should act according to the will of the Lord, that it should adapt itself to his commands. Rather we ask the Lord to carry out the wishes of our mind.

How often do we find ourselves doing this? We say that we live in the will of the Lord, but is this any more than lip service? Don’t we pray to him for things to turn out as we want? When difficulties occur in our lives - such as financial loss, bereavement, marriage breakdown or serious illness - we bemoan our circumstances, rather than saying to the Lord: “Thy will be done.”

Perhaps it is, for most of us, too much of a leap to surrender our mind to his will. In that case, we can start gently, by remembering that we are also practising this submission of the mind every day when we give time to meditation. Progress towards inner surrender is a journey; surrender its endpoint. The journey can start with the first step of a conscious effort of submission. In Die to Live, Maharaj Charan Singh says:

Just give yourself to him. To love somebody means to give yourself without expecting anything in return. To give yourself, to submit yourself, to resign to him is all meditation. We are losing our own identity and our individuality and just merging into another being. We have no expectation then. Expectation comes only when there is I-ness, that I exist and I want this. When I don’t exist, what do I want? In love you don’t exist. You just lose yourself, you just submit yourself, you just resign to his will.

Maharaj Charan Singh says that to submit oneself and to resign our lives to the Lord is in itself a form of meditation. Conversely, when we sit for the prescribed period of meditation each day, then submission of the mind is exactly what we are practising. Submission is meditation, and meditation is submission.

Gradually over time, the effects of regular, devoted meditation will be felt in our lives. Our practice of daily meditation will support us in adapting our mind to his commands. The submission of the mind will lead to love of the Lord, which will wear down the ego, and evolve into an acceptance of whatever the beloved wills. Maharaj Sawan Singh describes this mind state in The Philosophy of the Masters, Volume III:

The devotee feels that the Lord is always with him. He hands over all his sufferings and worries to him and is unmoved by either pain or pleasure. He is convinced that the Lord is thousands of times more intelligent, wise, strong and merciful than himself, and that he looks after his devotee and is his greatest well-wisher…. He surrenders everything to the Lord and says, “O Lord, you are the refuge of all living beings. You came here for the sake of all. Whatever you will is good for me. This is my only prayer.”

This feeling of acceptance, which we can work towards, is a beautifully quiet, joyful and liberated state. It is not yet complete surrender, because that can only happen inside when the individual mind has merged into the whole. But acceptance is the mindset on this plane that is the springboard to the non-existence of self and the bliss of true surrender and God-realization. Maharaj Charan Singh explains this in Die to Live:

Real surrender comes only by meditation. Resignation or surrender or living in his will - they are practically one and the same - you can achieve only when you go beyond Trikuti. As long as the mind is dominant there’s no surrender, there’s no living in the will of the Father, there’s no elimination of the ego. You can achieve real surrender only when all coverings are removed from the soul. Then the soul shines, it becomes perfect, and then it is capable of merging into the perfect being. That is real surrender.

This inner surrender of which the Masters speak is just a concept to us while we are still under the sway of the mind. It is impossible to understand it truly until we reach that point in our spiritual development where this amazing thing actually happens inside us. In Quest for Light, Maharaj Charan Singh writes: “One day we have to achieve this state and the method given to us by the Masters is only for this purpose.”

So all we can do now is to cultivate within us an acceptance of the will of the Lord, from the love we develop through meditation. With his grace, this will take us a step further towards inner surrender. Maharaj Charan Singh explains in Spiritual Discourses, Volume I:

The real surrender consists in withdrawing one’s attention from the objects of the world and attaching it to the Word or Nam. It is to turn one’s back upon the world and one’s face towards the Lord. The greatness of the inner surrender is unique and it comes about only when, through the practice of Surat Shabd Yoga, we see within ourselves the Radiant Form of the Master. Once this has happened, there is no wavering. We develop an unshakeable faith in the Master and our love and devotion to him are boundless. Then alone do we comprehend the greatness of the Master.

He is saying that it is simple: we just have to give up the objects of the world and turn towards the Lord. A certain Sufi mystic has a beautifully succinct formula for total surrender; it is simply this: “You do the giving up, and he will do the giving.”

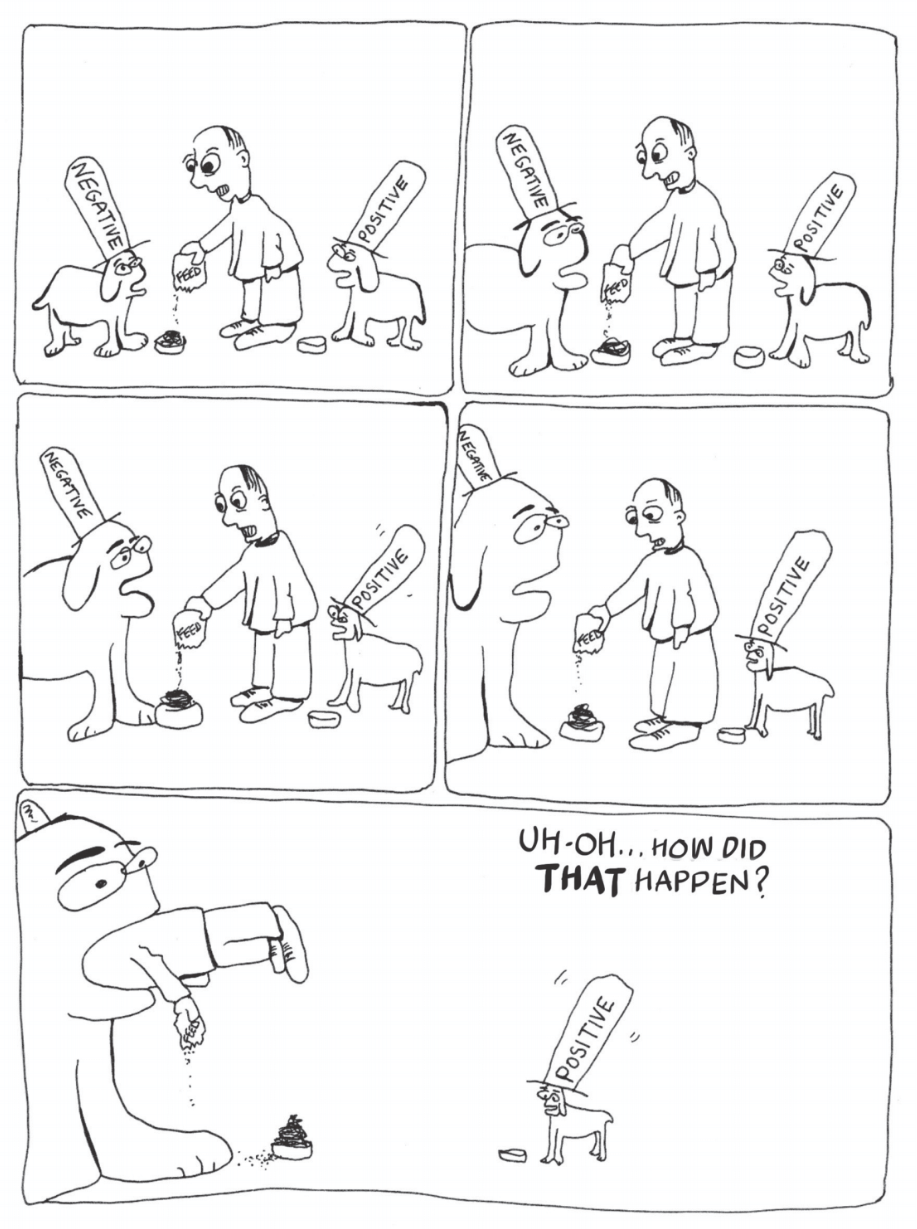

Feeling Funny

You are what you eat

Have Courage

Nelson Mandela once said that courage was not the absence of fear, but the triumph over it. The brave man or woman is not someone who feels unafraid, but one who has learned to conquer fear. And the ancient philosopher Aristotle said that courage is the first of human qualities because it is the quality which guarantees all other qualities.

In other words, courage is the most important of all virtues because without it we cannot practise any other virtue consistently. Our lives are filled with ups and downs; no one can skate through life without any problems. And if we try to run away from our troubles, we only delay our growth and end up suffering more. We have to face up to these difficulties, with courage.

When we are going through a stormy period in our lives, instead of saying, “Master, why me?” we should ask, “Master, what can I learn from this? Master, please give me the strength, the courage to go through this.” As is often said: life isn’t about waiting for the storm to pass; it’s about learning how to dance in the rain. What the Master is trying to teach us is just that: how to dance in the rain.

The most painful experiences have a constructive purpose behind them. And, like everything in this world, suffering cannot last forever. Successful author J.K. Rowling once said that at one point in her life, “I was the biggest failure I knew” - she had a failed marriage, she was jobless, and poor. But she saw in that failure an opportunity.

It enabled her, she said, to stop pretending to herself that she was anything other than what she was, and to begin instead to direct all her energy into what mattered most to her. Had she succeeded at anything else, she might never have found the determination to succeed in the one arena in which she truly belonged.

J.K Rowling’s failure acted, she believes, as “a stripping away of the nonessential”, allowing her to see clearly what for her was most important in her life. So failure in this world can be a true blessing, because it can refocus us towards our real work. And what is the only work that matters to us, as satsangis? What is the one arena in which we truly belong? It is the spiritual life, of faith and meditation.

Whatever difficulties we must go through are, the mystics tell us, the result of our own past deeds. The individual is, in this sense, the maker of his or her own destiny. But we need not see our sufferings as a punishment for misdeeds; if they push us towards the right path and contribute to our spiritual growth, then they have benefited us. When we are finding it tough to get through life’s troubles, it can help to remember this. If we can assert a positive outlook towards everything in life, we will be able to face our obstacles with courage.

Shun negativity

So we should try not to become discouraged and let negative thoughts dominate us. Our minds can become cluttered by little thoughts such as ‘I am afraid’, ‘I cannot do it; it’s too hard’, or ‘something terrible will happen’. But the saints tell us that nothing is insurmountable; ultimately, it all lies not in our hands but in those of the Master, and he can do anything.

In initiating us, the Master gave us the opportunity to discover an ocean of love and bliss. But before we can embrace our mysterious reality, we must first start walking away from the secure illusion in which we live. This usually requires an enormous amount of courage. Without courage, we cannot move forward on this path.

When we hear about the bravery and the courage of the saints and their ardent love for the Lord, we find ourselves so inadequate. But then, discipleship is not about being perfect, it is about striving for perfection. It is not easy to bring back our attention over and over again in meditation when the mind keeps dodging us. It is not easy to accept the hard blows of life that strike us because of past karmas. It is not easy to smile at the world when the soul is deeply aching for something more meaningful. But when the Master accepted us for initiation, he never said it was going to be easy.

Effort is all

And yet Baba Ji has made it easy for us, if only we learn to live in his will. All the Master expects from us is that we put up a courageous fight, against the mind. The result of that fight is not something with which we should concern ourselves: there is no such thing as success or failure in spirituality, only effort or the lack of it.

Sometimes we are able to control the mind and sometimes it will control us; this is why, as disciples, we need the courage to continue without losing heart. Somebody once told Hazur Maharaj Ji that before coming to this path he had been scared of death, and now he was scared of life. Hazur replied that we are all struggling souls but we are never alone; and then he said: “Have courage.”

Courage is a quality that is developed as we keep practising, just like a muscle that becomes stronger with constant exercise. Initially, we can just pretend to be courageous, but eventually we will find we have built within us an unwavering inner strength. Times of misery are our biggest benefactors, because they give us the opportunity to build up that muscle of courage.

The finest steel is produced from the hottest fire. Similarly, each of life’s many challenging moments offers an opportunity to experience the Master’s grace, to put our faith in his love, and to strengthen our courage. We need to take each heartache, each moment of hopelessness, each instance of doubt, each anxious cry, and turn it into unrelenting courage. When the Master sees us trying, he has no option but to embrace us, no matter how unworthy we may be.

What pleases the Master most, of course, is to see us trying in our daily meditation. Baba Jaimal Singh once wrote in a letter to the Great Master that even if our attention remains focused for only one or two minutes, the news of our effort will immediately reach Sach Khand. Meditation awakens and nourishes the love within us. It is the process by which we strip away the non-essential and focus on the essential.

Love always trusts, love always hopes; love always perseveres with courage. Winston Churchill once said that success is the ability to have the courage to keep going without losing our enthusiasm. We should never dampen our enthusiasm by criticizing our own efforts, however small, because every little bit of effort is a step forward. We know we can achieve God-realization in this lifetime, because the Master has told us so. We need only to build the courage to keep steady on this path.

Look to this day! For it is life, the very life of life.

In its brief course lie all the varieties and realities of your existence;

The bliss of growth,

The glory of action,

The splendour of beauty;

For yesterday is but a dream,

And tomorrow is only a vision;

But today well lived

Makes every yesterday a dream of happiness,

And every tomorrow a vision of hope.

Look well therefore to the day!

Attributed to Kalidasa

Already There

Moving to America was something we had always known might happen, although for a long time it was only a vague idea - and a neutral concept, neither desired nor feared. At some point it turned into a possibility, invoking first ambivalence and then, increasingly, attraction. Quite suddenly, it became an opportunity, at which point we had to decide in earnest: did we want to go, or not? Were we ready to make this commitment to totally change our lives?

It was a huge decision, and one we would be making on behalf of our children as well as ourselves. And yet, in the end, it was not a difficult one. Despite our pangs at everything we would leave behind, all those attachments in our old world, there was a strong sense that we just had to go. That this was our destiny; America was where we were meant to be at this point in our lives. It felt right.

A decision that is not a decision

Anyone who has ever made the decision to apply for initiation will understand that feeling. You just know it has to be done; the decision is not even a decision, because as soon as you begin to consider it, you realize it’s already been made. This can happen almost as soon as one first learns about the path, or a long time afterwards. Especially for those who have been close to the path since childhood, initiation can seem for many years a remote, if eventually inevitable choice; even after attaining the necessary age one may be in no hurry to apply. The pull is not there, or not yet powerful enough. But one day, perhaps quite suddenly, it is.

Of course, having applied for and then (with the Master’s grace) gained the gift of initiation, we realize that we have arrived only at the beginning of our journey, not its end. We have much work ahead of us, to prepare our soul for its voyage. And although we understand that each tiny step - each moment of true effort - really is taking us forward, there are times when we may begin to lose heart. Faith can slip away, in the face of the huge distance yet to be travelled.

After many years of meditation, we may feel that we have hardly moved forward from our starting point - or worse, that we seem to have travelled backwards. In such a state, it is hard to believe we will ever reach our destination. Early one morning, not long after having made the commitment to move to America, I was beset by just such despondency. Sitting down cross-legged, pulling my shawl over my head, I was overwhelmed by a desperate sense of how very far there was to go before I could feel even close to approaching that spiritual endpoint at which satsangis all aim.

My whole being seemed so far removed from anything like a state of readiness for salvation; if anything, my faults seemed to be growing rather than shrinking. How is it, I cried inwardly, that we are told by the Master that we are already there, and yet clearly, clearly, I at least am so very far away from being there.

Do what has to be done

And in the next moment I thought of our approaching move to America: how much was yet to be done to implement the relocation, how many lists and lists of things to do - visas to acquire, a home to rent, schools to find for the children, a car to be sold and another bought, a tenant found for our house in England, the shipping of all our furniture - and yet it was already quite beyond doubt that we would go, that in a few months we would, quite simply, be there.

One way or another, the arrangements would be made - not without huge effort on our part, of course, and yet somehow not dependent on that effort. It would happen; it was to all practical purposes impossible now that it could not. On the appointed day, we would find ourselves sitting on that aeroplane, clutching our one-way tickets, soon to land in America, our new home.

The time that separated us from that day was already measured out. All that was needed was for us to do what had to be done, with diligence and faith. That time would pass, and we would be there. And then I saw, suddenly, that this was not quite accurate - it was not in fact that we would be there.

No. We were already there.

Not What We Thought

The way of union is

not what we thought.The world of soul is

not what we imagined.The Fountain of Eternal Life

is closer than you think.The Water of Life

is in this very house -

but still, we need to drink it.

Sadr al-Din Qunawi As rendered by David & Sabrineh Fideler

Sun at Midnight

In Tales of the Mystic East we find the following story:

Once, in the thick of night, Guru Nanak Sahib said to his sons, “Look, how magnificently the sun is shining.” His sons were incredulous.

When he made the same comment to Guru Angad Dev, he replied, “Yes, how magnificent it is.”

Guru Nanak then said to him, “Go and wash these clothes, dry them, and bring them back to me.”

There in the darkness of the night, Guru Angad did as he was told. The clothes were washed and dried as in the bright hot light of day.

The words of saints are impregnated with meaning and it is unwise to doubt them.

In this surprising little story we get a view, amongst other things, of how hard it is to follow a saint. Only Guru Angad Dev (another saint) was able to do so - Guru Nanak’s sons were left “incredulous”. Saints do not come to corroborate our worldview and make us complacent, but to turn it upside down so that they can root us in a better reality.

As disciples, we may intellectually believe that we have complete faith in our Master. We may feel that we would carry out whatever he advises, even if we do not understand it, that we would accept as right whatever he arranges. But the fact is that when these situations arise, for instance in our seva, in connection with satsang arrangements or simply in the circumstances of our personal lives, we forget entirely about our theoretical belief and let our mind surge forth with its array of judgments.

What would we have said if we had been one of that little group on that dark night with Guru Nanak? Would we have been keen to proffer our worldly knowledge?

“Oh Sir, the meteorological office this evening said that sunrise will be at 6.05 a.m. Should we perhaps wait?”

“Hazur, we would like to do this, but unfortunately, health and safety legislation won’t allow us to wash clothes in the dark.”

Or simply, “Sir, it just isn’t going to work …”

Would we have done everything we could to avoid the foolishness we feared feeling as we hung washing out to dry in the middle of the night? Because, of course, our mind would have been telling us how crazy it was.

The limits of logic

We’re not in an easy position, because we have been brought up to be logical human beings. We must be sensible human beings! Not only our schools and colleges but also our modern-day Master encourages us to use the common sense that most of us have been given. In satsang, for instance, we are advised to employ the power of logical thought to identify our objectives in life, and then to apply that same power in reviewing whether we are doing what it takes to realize these objectives. Logical thought, here, is an adjunct to leading a spiritual life. Maharaj Jagat Singh, writing in A Spiritual Bouquet, advised satsangis to use their heads rather than their emotions when facing life’s ups and downs: “Satsangis should form the habit of ‘thinking’ - clear thinking”, he said. So our mind can clearly be useful in guiding us towards right action.

The mind is an excellent tool, and when we use it well we find it guides us through many situations. As small children in nursery school, some of the first exercises we carried out involved the task of sorting one category of object from another. The items we were given could have been abstract shapes or colours, or models of various types of bird, animal or other object - the point was to give practise in identifying difference and making small, fundamental assessments such as: “This thing has legs and also wings, so it is a bird; this other thing has four legs but no wings, so it is an animal,” and so on. Before long, we had become adept at putting things into categories and, with every apparently successful judgment that we made, our sense of what the world is and how we could understand, control and survive in it grew stronger.

Coping with contradiction

But having grown strong in worldly experience, what are we to do if someone in whom we have placed great trust, our Satguru, decides to contradict our world picture? How do we feel if he tells us that the sun is shining when we firmly believe that it is not? Is he teasing us? And, if so, why does he tease? Actually, of course, there should be no need to provide ourselves with any answer to this. The Guru is the Guru is the Guru, and we should carry out whatever he advises without intellectualizing and without a moment’s hesitation. But because we are also what we are, and because he has told us to use our heads, then let’s do just that in thinking about this particular story.

It will help if we return to the understanding that the mind is a tool. Let’s be clear that that is all it is, and that, like all tools, it belongs in certain situations and not in others. In dealing with the world, it is appropriate to use it; on first contact with the spiritual path, it is sensible to subject that path to careful scrutiny and to satisfy ourselves completely that this is the way, and that this is the Master for us. For instance, in Spiritual Perspectives, Volume I , Maharaj Charan Singh says:

Even if we spend our whole life in trying to understand what we have to follow, I say the time is not lost, it is gained…. We must satisfy our intellect to the best of our ability.

But when we really engage with the nature of discipleship, we come to realize that the mind is a servant, not a god. If it has come to believe that it is more than a servant, then it must be put in its place. Because the Masters are denizens of regions beyond the mind, it follows that the laws of mind and matter hold no sway over them. We hear at the end of the story that the clothes were dried as in the bright hot light of day. Of course they were. That was the power of the saint. More importantly, if we are to rise above mind and matter, then we have to learn to put absolute faith in our Master over the workings of mind.

We are rather like people who have fallen into deep water (the world) and are now surviving by treading water. A lifeguard (the Master) dives in to rescue us. Treading water was useful before he arrived, but now that his arms are around us we must just trust in him and let ourselves be carried to the shore.

We will go on using our worldly intelligence to the best of our ability, but the moment we sense that that intelligence is a hindrance, rather than a help, we must leave it behind and keep faith in the Master. Maharaj Charan Singh says:

We must make full use of our intellect, but once we are convinced that this is the right path for us, this is the right guide for us, then we are not to worry with our intellect but should set it aside. What we need then is practice, faith and devotion.

Spiritual Perspectives, Volume I

Are You Sitting Comfortably?

I’ve been struggling with my meditation. Have you? In the first two years euphoria carried me along, but after that my attention and determination slowly weakened. Just as the initial flush of romantic love brings such eagerness to please one’s beloved that nothing is too much trouble, during the initiation honeymoon it feels natural, even easy, to put all one’s energy into meditation. But that early high may not last.

I found that my initial ideas about meditation were increasingly challenged by actual practice. Unwittingly, I also allowed the focus to shift slowly away from spirituality, becoming preoccupied instead by worldly life. One day it was suddenly clear that there was no longer the same zest to practise for two-and-a-half hours. Meditation had become a battle against circumstance, against mind and body - a fight that I had never expected to join.

For a while, this state of affairs continued unchallenged. Then I began to mull over the possible reasons underpinning this struggle and how I might take responsibility for attempting to overcome my difficulties. A resulting awareness developed: that once the initial exhilaration of being initiated and the consequent enthusiasm wear off, it is our responsibility to find a way – our own way – of sustaining ourselves on the path. In so doing, we begin to develop a deeper, experiential understanding of Sant Mat and, hopefully, a more mature relationship with the inner Master.

These reflections are helping me gradually come to a deeper appreciation of what meditation is and the scope of my role. I don’t have all the answers, but I have gained a few small insights about nurturing one’s meditation so that it becomes less of a struggle, more joyous - and, dare I say it, more interesting. These insights, which you may or may not already have come to by yourself, relate to preparation, to focus, and to identifying the goal of meditation.

Preparation

Across the globe during the hours of dawn, when most people are still asleep, initiates awake to meditate. However, you’ve probably come to realize that more is required than simply turning up for our daily session. Regularity and punctuality are essential, but on their own they do not lead to ‘quality’ meditation and can even breed complacency. At this point, you may be thinking, “Stop there! The results of meditation, or even its quality, are not in our hands but those of the Master.” Yes, that’s true. But I’m talking about the quality of our effort - and that is most definitely in our hands.

Our effort doesn’t stop at turning up; that’s only the first step. The most important part is the degree to which we repeat each round of simran with as much single-pointed attention as we can muster. Achieving maximum concentration in our simran so that we can step through the tenth door and meet the Radiant Form of the Master is an ideal we’re trying to reach. On the ‘good’ days, we can probably repeat simran with sufficient focus that we’re aware of the names despite the constant images and thoughts rushing through our minds in the background. And even when the mind tries its very hardest to turn our attention outwards, we have the strength to resist and keep it occupied in simran.

Yet there are days when no matter how hard we try, the mind seems to have the upper hand. Flitting about from one thing to the next, it refuses to repeat simran, preferring instead to focus on the minutiae of daily life. In this frustrating situation, it is easy to become deeply dissatisfied with ourselves and our so-called progress on the path. However, before we dismiss ourselves as failures and our determination begins to wane, a little more introspection is required. Why exactly is it that we can’t focus on our simran in the way we desire?

To answer this, first we need to ask ourselves the extent to which we repeat simran throughout the day. As Baba Ji says, the mind is like a computer: whatever we download into it, that’s what we get back. If much of our time is devoted to ‘compulsive thinking’ - the process of abandoning ourselves to the inner chatter of the mind - it will come as no surprise that when we sit for meditation, our mind refuses to co-operate. If, however, we constantly look for opportunities to repeat simran, such as when performing mundane tasks, this can help us stop the habit of compulsive thinking. This is because there is an inherent power in simran, which helps to purify the mind.

Our level of attachment to the world may also help to explain why we find it difficult to repeat simran in the way to which we aspire. We are told that the more detached we become, the greater our level of concentration. But where does that detachment itself come from? It emerges from focused meditation, and focused meditation will occur as a result of ceaseless simran. So, once more we return to the practice of spiritual simran. Of course, underpinning all this is the Master’s grace.

Focus

Improving our effort in meditation requires focus. We all know that the focus of our meditation should be the Shabd, and to achieve this we practise simran as well as contemplating on the form of the Master who has initiated us. Sometimes, however, we focus more on ourselves than on the Master. The mind plays many tricks on us. As well as conjuring up thoughts about the material world, it also has the tendency to focus on the process of meditation at the expense of the practice itself.

We become preoccupied by our posture, fighting against ourselves not to shift position, obsessed with whether we’re pronouncing the five names accurately, wondering whether the numbness we feel in our limbs means our consciousness is rising, wishing we didn’t feel so sleepy, and so on. One of the biggest tricks the mind can play on us is when we start holding a conversation with the Master during meditation. We can fool ourselves into thinking that this is equal to meditation, or not as bad as thinking about material issues.

Perhaps it is through struggling with the challenges of making the mind and body motionless that we finally come to realize that our efforts are actually quite puny. We overcome the misconception that it is ‘my’ efforts that will achieve the goal. When we contact the Radiant Form of the Master and eventually reach Sach Khand, we will do so because of his grace and not because of our performance. Eventually we truly understand that meditation is not about you or me - it’s about him! Then we begin to see that it doesn’t matter exactly how we’re sitting or pronouncing simran; our focus should simply be directed to repetition.

Goal

Finally, our efforts in meditation can be improved by clearly identifying our goal. When we’re first initiated, many of us see the goal of our meditation as being to meet the Radiant Form of the Master and reach Sach Khand. However, the more we practise, the more we begin to realize that there is no goal other than pleasing the Master. We stop becoming anxious about ‘results’ and ‘progress’. Instead, with our attention focused on him, we (try to) meditate for no other reason but love and begin to accept that what he does is up to him.

We can draw encouragement from the insight shown by Brother Lawrence in The Practice of the Presence of God, who said that he “endeavoured to act only for him; whatever becomes of me, whether I be lost or saved, I will always continue to act purely for the love of God”. He did not seek God for salvation or reward; rather he resolved to make the love of God the end of all his actions. Understanding that our original aims in meditation are beside the point, we begin to have a different reason for leaving our warm beds in the morning. And that is love for and faith in the Master.

We may not feel like we’re in love as we get up each morning and shake off our slumber: indeed, we’re more likely to be feeling tired, fuzzy-headed, and distracted by worldly worries and excitements. We’re probably not feeling the kind of intense love for the Master that comes so easily when we sit before his physical form. But although that feeling may not be uppermost in our consciousness, it is still there. Why else would we give our time to meditation at all?

We begin this journey fairly egotistically - thinking “I’m in love with the Master,” or “I want initiation,” or “I want to reach Sach Khand.” Then slowly and subtly a transformation starts to happen. Our ego begins to ebb, and pleasing the Master by practising our meditation, regardless of outcomes, starts to become more important. We come to understand that it is not through the force of our ego that we are going to reach our journey’s end, but through taking practical steps to follow closely the Master’s instructions, putting in our best effort, and then leaving the results to him.

From the Master, ask for the Master, for when he grants you that, you will get everything with him.

Spiritual Gems

Give the Master a Chance

Between Master and disciple there is a relationship of great strength, but our limitations mean that we often fail to recognize this, or indeed to appreciate it. The saints often say they would be nowhere without their disciples, although of course it is the disciple who needs the Master and not the other way round. The present Master has said that he would be out of a job without us, and it’s certainly true that we keep him busy. There is no limit to his efforts in trying to lift us, encourage us and cajole us in the right direction.

The mind troubles us continually, and often it seems we are in a constant battle of some kind. Either we are fighting our destiny, or blaming the Lord for not fulfilling our desires, or simply struggling in our relationships. And sometimes we feel at odds with the path because it can be difficult to follow or might seem to be preventing us from enjoying life’s worldly pleasures.

While struggling with all this, we may miss the obvious solution to our problems: the strength and courage we can draw from our relationship with our Master. Too often, we don’t even give it a chance. Instead, we battle even against him. This may seem a harsh thing to say, and difficult to believe, but our deeds suggest that it is true.

We avoid meditation or fail to give it our full effort; we compromise our principles at the first sign of trouble; we constantly seek shortcuts in life and on our spiritual path to avoid doing what we are required to do…. The list goes on.

In reality, we are not even giving our Master a chance to help us. He is not here to put difficulties in our path; no loving parent would ever do that to his children. And saints have nothing but infinite love for their disciples - this much, at least, we surely cannot help believing. From this core belief can emerge a gradual strengthening faith that the instructions given to us are for our own benefit. When we put those instructions into practice, wholeheartedly, then our limited faith will begin to grow firmer.

Whatever our Master asks us to do is always the shortest path to salvation. He does not want us to be here a second longer than necessary; in fact, his own seva is not complete until all the disciples for whom he is responsible have reached Sach Khand. And all he asks of us is that we do our meditation, avoid intoxicants and meat, and live a moral life. Every instruction he gives us is the easiest possible way to get back home.

So, let us give our Master a chance to help us - let us believe from the heart that he is always doing what is best for us and that he is not here to make things difficult or to test us. After all, if the Master really chose to test us, not even a handful would pass. Let us work with our Master and not against him. When we start to do that, we will truly feel the warmth of his love, and automatically gain the strength and courage to face our destiny in good cheer.

“The inferno of the living … is what is already here, the inferno where we live every day, that we form by being together. There are two ways to escape suffering it. The first is easy for many: accept the inferno and become such a part of it that you can no longer see it. The second is risky and demands constant vigilance and apprehension: seek to learn and recognize who and what, in the midst of inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space.”

Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

Turn Around - Listen

Turn around and listen

to the great resonance of Shabd.

These opening lines of a poem by Soami Ji sum up the entire philosophy of Sant Mat, the teaching of the saints. What the poem, Shabd 12 from Bachan 20, tells us is that we must turn our attention around. Our hearing is normally focused on external sounds, but we need instead to listen to what is within us.

Moreover, we must not just hear but actually listen; it is a matter of attention. When we don’t notice the birds singing, it’s not that we can’t hear them but that we aren’t listening. We are not giving them our attention. The saints repeatedly tell us that the Shabd is there, but we are not; we can hear it but we’re not listening. Our attention is elsewhere, drawn by external sounds.

The mystics tell us that God cannot be found outside, in the realm of the senses. It is not just that we interpret the world through our five senses; what we perceive through them is what we take to be real. Most of us regard ourselves as practical people, who won’t believe something unless we’ve seen it with our own eyes. Yet we know from science that human eyes see only a tiny fraction of what is there; with X-ray eyes, we’d see a different world. Far from seeing reality, we see only what’s on the surface.

Psychologists explain that when we see another person for the first time, we form a judgment about them within seconds, mapping what we see onto our prejudices. When we get to know that person better, we always discover that he or she is different from our initial perception. Seeing may be believing, but it isn’t knowledge. It’s the same with all our physical senses.

But the saints tell us that we do have reliable faculties for accessing reality, namely the inner spiritual faculties. Referring to Sant Mat as ‘the science of the soul’ is a way of explaining this idea. No one expects to see a ‘soul’ in the outside world, so the word ‘soul’ stands for whatever lies within. The science of the soul is the experiment of going within to find reality.

Soami Ji continues his poem:

O surat, beloved of your Master!

Why carry heavy burdens on your head

when your stay on earth is so short-lived?

The Master pleads with you again and again

to develop love for the melody of Shabd.

Surat is the inner hearing faculty. By “heavy burdens”, Soami Ji does not mean the events of life. These are the results of karma; sometimes immensely enjoyable, sometimes horribly painful, mostly somewhere in between. He means rather the burdens of mental attachment - to beings, objects and events in this world.

We believe that what goes on in our world matters profoundly, because this is the only ‘reality’ we know. Yet as spiritual human beings we are constantly seeking happiness, fulfilment and liberation. Here is the paradox. We want happiness and we see the outside world as real; but if we seek happiness through the senses, we won’t find it.

There are two major reasons why we won’t find happiness ‘out here’. Firstly, everything here changes. If our happiness depends on other people, we cannot guarantee they’ll remain happy, healthy or here at all. And sooner or later we realize that our own time is limited too. Our human life is measured in breaths; at any second we may use up our allowance and leave. Knowing this, how can we expect to find any lasting happiness here?

Secondly, our desires will never be fulfilled. The more we gain, the more we want. Maharaj Charan Singh described indulging our senses as putting fuel on the fire. We came into this world empty-handed and we will leave empty-handed. What lasting happiness can be obtained by trying to have more and more? In the Bible Jesus Christ asks: “For what does it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world and lose his own soul?”

Soami Ji does not recommend that we cut all our ties to the world, however. It is wrong for us to abandon our responsibilities and live off others. He advises us instead to loosen our mental attachments while living a normal life:

When all worldly attachments are shaken loose,

the soul has taken the first step on its way to Agam Desh.

When we want to transplant a shrub we have to remove it with its roots intact or it will die. A plant with deep roots will resist being dug out, but once it starts to loosen we can shake it so that the roots are freed intact and it can be successfully transplanted. The saints tell us that mental attachments similarly can be loosened, by stilling and focusing the mind, so that we may transplant our attention to the Shabd within.

By practising meditation regularly and punctually each day, regardless of our changing circumstances, we learn to meditate in a natural, relaxed way. Like learning to speak a foreign language or play a musical instrument, we have to work through a period during which the process may feel artificial and unnatural, in order for it to eventually become natural and automatic. Habit becomes nature.

Meditation is naturally a struggle. Our effort is the Master’s grace. Most of the time we can offer the Master only our ‘failure’ in meditation, but we can fail only if we try. We may experience setbacks, but a setback can happen only to someone trying to go forward.

Soami Ji goes on:

This is no task for the worldly minded;

only a gurmukh can understand and accomplish it.

Manmukhs have entirely lost the game of life.

But if they attend satsang,

even they can overcome their evil tendencies.

A gurmukh is one devoted to the Shabd form of the Satguru within. A manmukh is under the sway of the mind, the senses and the passions. When Soami Ji refers to manmukhs as ‘they’ he is being rather kind; he means us. We can all talk about the Master, the Shabd, love and devotion, but without meditation this is all just words.

Soami Ji goes on to say:

Nam alone is pure, all else is bitterness, poison;

make Nam the sustenance of your life.

The present Master has described meditation as our life-support system. We think we are sustained by food, water, warmth, and so on. However, these things sustain the body, not the soul. If we focus on sustenance for the body, to the exclusion of food for the soul, we will remain fully attached to the world.

Soami Ji advises:

Listen to me, stop being apathetic -

wake up, pay attention.

Uproot and destroy lust and other passions,

then wash yourself clean

in the refreshing stream of Shabd.

If we commit ourselves to daily meditation, if we wake up and pay attention, we will uproot and destroy lust, anger and the other passions. The saints explain that we will be truly detached from the world only when we are immersed in the “refreshing stream” of Shabd; what Maharaj Charan Singh often called “that better pleasure” within.

Soami Ji continues:

When you conquer your mind and maya,

both Kal and karma will also be ousted.

Then the soul will be in command -

free to ride to the palace of the perfect Master.

Once connected with the Shabd within, the soul is no longer under the sway of the mind and the mind is no longer the slave of the senses. Soami Ji concludes his poem with an affectionate address to the soul who has followed the advice of the Master. For this one, he says, there is only enduring bliss and real happiness:

Dear soul, you are the consort of Agam Purush,

you have now become the beloved of all.

Strengthen your love for the perfect Master

so you can see the splendour of Shabd within.

The Accommodation of Longing

Seeking Nam is a little like falling in love with someone of whom your family disapproves. The ‘family’, in this case, are your worldly involvements, habits and desires, which don’t want anything to alter their comfortable status quo, while Nam, of course, is the loved one. There comes a point when you must ask yourself: how much am I prepared to give up for my beloved?

A close friend called me one day to announce that she and her husband were expecting a baby. She was happy and excited; but she was excited about a lot of other things in her life too. She lived actively and diversely, to an exceptional degree: deeply immersed in culture, sport, friendships, work. One of her many passions was cycling. It was a cold April that year, and one weekend soon after learning about the baby she and her husband went cycling in the mountains, undeterred by predicted bad weather. A few days after returning, she miscarried.

She was hard hit emotionally; it wasn’t the first pregnancy that had failed to work out for her. But the doctor said: don’t worry, when you are really ready for this, when this is genuinely what you want more than anything, then it will happen for you. There are many reasons why a pregnancy may fail; most often they are physical. But in this case the doctor seemed to sense in her a certain lack of focus, a confusion of priorities.

My friend went home, worked through the sorrow of course, but also re-ordered her life. She had to decide which of her many interests and desires were really important to her, and which not. She made some sacrifices, and streamlined her life; she accommodated her longing. A short time later she conceived again, and nine months after that her first child came into the world.

We can think we dearly want something, but unless we’re prepared to focus on it completely, and in a logical way take the practical steps we know are necessary to achieve it - such as giving up other desires that might stand in its way - then maybe that longing just isn’t great enough yet. The same is true when we approach initiation.

We must ask ourselves: “How much am I prepared to give up in order to gain my heart’s desire?” Unless the answer is “anything, and if necessary everything”, then that longing is not true. It’s highly unlikely that we actually would have to give up everything, but there cannot be a single thing that we aren’t ready to give up.

And if we really are ready to give up anything in order to gain our heart’s desire - if our longing for Nam is that strong, but we cannot yet obtain it for some practical reason, such as not yet meeting the age requirement or some other criterion - then we must simply enjoy that feeling of longing. Unfulfilled longing can bring a pain that feels at times intense, but there is a seed of joy at its core, and that is something to treasure. The experience of that intense longing - the impression made deep within us of its strength, of its pain and its joy – is something that will carry us through later, during times when our enthusiasm might waver. On finally receiving that gift of Nam from the Master, the commitment to meditation will be all the stronger in remembering the pain of that longing.

And we are put on earth a little space,

That we may learn to bear the beams of love.

William Blake

Keeping It Real

It can seem astounding that something said thousands of years ago can be so relevant to our lives right now. Socrates, who lived in the fifth century B.C.E, was known in his own time and still today as a philosopher. “Philosopher” in its truest sense, in direct translation from the Greek, means a lover of wisdom. It wasn’t worldly wisdom that Socrates was in love with, but the pure wisdom or truth that only the soul can experience.

It was Plato, a follower of Socrates, who preserved the teachings of his master, making these ideas available to others to understand and follow down the ages. Plato wrote many dialogues, representing the conversations that Socrates would have with his disciples, delving into the depths of the human psyche and human reality.

Greek philosophers such as Socrates didn’t just talk about wisdom but also practised it in their daily lives, bringing it into everything they did. Robin Waterfield, a prominent translator of Plato’s works, explains how Socrates’ philosophy was as much a way of living as a system of ideas:

It is important to remember that philosophy for Plato was not, or not just, confined to lectures and books: it was a way of life. His purpose was to get his readers to change their lives, to undertake the pursuit of assimilation to God.

Socrates understood that to get to the absolute truth you have to look beyond this world, which he saw as a world of illusions. His allegory of the cave, in Plato’s most popular work, Republic, uses a metaphor to illustrate the illusory nature of human reality. It describes a cave in which prisoners have been tied up all their lives. All they can see is a blank wall on which shadows move, made by things passing in front of a fire behind them. Because they cannot see the things themselves but only their shadows, the reality of the shadows is the only reality in which these prisoners can believe.

Socrates says this situation is an analogy for the human condition. How perfectly he describes us as prisoners in a world of darkness, full of shadows. We see only what passes in front of us, unable to view things from a truer perspective and as they really are. We believe that these shadows are the truth and it does not even occur to us to imagine they might be a mere shadow of reality.

Plato goes on to describe in the Republic how, when a prisoner is set free from the cave and sees where the shadows are being projected from, he is “too dazzled to be capable of making out the objects whose shadows he’d formerly been looking at”. When we, like the freed prisoner, catch a glimmer of the real, we may be taken aback and stumble back into our cave, not wanting to destroy the illusion we have been living in since birth.

Even when we see the truth with our very own eyes, we may still be unable to trust or believe in it, because we are grasping hold of the shadows so tightly. We are comfortable in ignorance. Our whole life is just shadows, and in another sense it is also only a shadow of a shadow of what it could be.

We are so burdened with the karma which has clouded our vision, that we can no longer imagine (let alone see) that anything could be more beautiful than what we see before us every day. Socrates believed that it was the body, and everything attached to it, that tainted us and imprisoned us like shellfish. As Plato writes in the Phaedo:

Every seeker after wisdom knows that up to the time when philosophy takes it over his soul is a helpless prisoner, chained hand and foot in the body, compelled to view reality not directly but only through its prison bars, and wallowing in utter ignorance.

The writings of Plato repeatedly use the image of the world as a jail house in which the soul is held captive and chained. But he believed that there was a way out. Plato explains on numerous occasions that it is the duty of every philosopher - every lover of wisdom - to free the soul from the body and its worldly ties, saying in the Phaedo that … in fact the philosopher’s occupation consists precisely in the freeing and separation of soul from body."

Plato believed that release from this world was a long, hard process. This is true. But how lucky for us that, once we have found our Master and been initiated, the long part is over! From this point on, it is just a matter of time and effort. This effort consists in fulfilling our duty and trying to become true philosophers, true lovers of wisdom, living that wisdom in our everyday life, every day. And in having faith in the Master.

We need to remind ourselves sometimes that what we see in the world is only shadows. But if even these shadows can be so beautiful -and the world has much beauty in it - then how awesome must true beauty be! And gradually we will move away from the shadows, unbind ourselves from our body day by day, thought by thought, until one day at last we are able to see the source of all shadows, and thereby gain true understanding and true bliss. As Plato says in the Republic:

And at last … he’d be able to discern and feast his eyes on the sun - not the displaced image of the sun in water or elsewhere, but the sun on its own, in its proper place.

The Light of Understanding

In the Gospel according to Saint Luke, in the Bible, it is written: “Blessed are those servants whom the Master finds awake when he comes.” Similarly, a story in the Gospel of Saint Matthew tells of ten maidens, of whom five looked after their lamps, trimmed their wicks and kept them filled with oil, and five did not. When their Master came to take them with him to the sacred wedding - the union with the Lord - those who had prepared their lamps lighted them and went with him through the door. Those who had not were caught short and could not go with their Master but were left behind lamenting.

This story emphasizes the importance of being awake enough, aware enough, to attend to our spiritual tasks routinely and regularly. It also shows how easily we forget, or do not understand, how vital it is to trim the wick and top up the oil in the lamp of meditation every day. If we do not grasp the importance of our task, we do not put in the effort to do it; instead we postpone it, forget it, and rationalize why we have not done it. Somehow we lose sight of the fact that when the critical time comes and we need the lamp to light our way, it will not be ready.

This story works on many levels and applies to many things in life. It points out how easily we slip away from doing what is necessary. If we don’t stick to our routine of getting up to sit in meditation because we do not appreciate its importance, we will not be conscious enough at the time of our death to see the Master or to go with him. Instead we shall be left behind to reincarnate in this cycle of transmigration.

In mystical texts from the ancient Hermetic tradition of Egypt, dating from the first three centuries C.E, Sophia - who symbolizes Shabd, wisdom and both the creator and creation - speaks about how essential it is that we understand why we should be awake to the Lord, to meditation and to life itself:

Hear me, you that hear

and listen to my words, you who know me.

I am the hearing that is attainable to everything,

and I am the speech that cannot be grasped.

I am the name of the sound

and the sound of the name….For what is inside of you is what is outside of you,

and the one who fashioned you on the outside

is the one who shaped the inside of you.

And what you see outside of you, you see inside of you;

it is visible and it is your garment …

On the day when I am close to you,

you are far away

from me, and on the day when I

am far away from you,

I am close to you.

Thunder: Perfect Mind, in Nag Hammadi Library

The ‘I’ in this poem is Sophia. In Gnostic texts she is the feminine God-principle, who filled all matter with scintilla - sparks of light and consciousness - to ensure that every aspect of the material universe would one day be able to return to the divine regions that are its source.

Mystics tell us such stories to open our minds to an understanding of spiritual realities. They explain to us that it is only through regular spiritual practice - trimming the wick, filling the lamp with oil, in other words, daily meditation - that we get near to understanding the Masters’ true nature. They tell us that if we truly understood what they are, we would never skip our meditation or fail to give it our full attention.

To understand something as truth, we need to wake up to the experience we have of it, both inside and outside. Meaning is pertinent to oneself, not to anyone else. Baba Ji advises us to think for ourselves about why we want to be initiated, why we should meditate. He tells us to prioritise what is important to us personally and then to act accordingly. We must each ask ourselves: “What does meditation mean to me?”

Once we experience the results of doing something, then we begin to understand more truly why we are doing it, and so our motivation grows. When we really understand what our actions mean for us, we will never slacken in our meditation, as we will understand that if we do, we are giving up a true and intimate relationship with our Master.

To understand is to be conscious. In a certain African language, the word for the sharp thorn of the mimosa tree (mva) is the same as the word for consciousness - the sharp sting of the thorn symbolizes the sting of being conscious. In Western traditions, light is often a metaphor for spiritual understanding. Hildegard of Bingen writes:

The Word is light that has never been concealed by shadow, never given a time to serve or to rule, to wax or to wane. It is, rather, the principle of all order and the Light of all lights, which contains in itself light.

What is being said here is that light symbolizes God, and being eternally awake - in other words, a spiritual consciousness.

If we have this consciousness, like the maidens with the well-tended oil lamps, we see things just as they are - with clarity, achieved through understanding and love. In this sense, understanding is an act of love enabling us to see and bear the truth of reality. When we understand this, we take on board the reality we experience in meditation, and we begin to understand our essential relationship with God, the Master and Shabd.

Here is an extract from the book Mister God, This is Anna, about a little girl who is talking to her friend Fynn about her relationship with God:

“Mister God made everything, didn’t he?”

There was no point in saying that I didn’t really know. I said “Yes.”

“Even the dirt and the stars and the animals and the people and the trees and everything, and the pollywogs?” The pollywogs were those little creatures we had seen under the microscope.

I said, “Yes, he made everything.”

She nodded her agreement. “Does Mister God love us truly?”

“Sure thing,” I said. “Mister God loves everything.”

The narrator, Fynn, then explains to Anna that there are “a great many things about Mister God that we don’t know about”, and she responds with another question:

“Well then,” she continued, “if we don’t know many things about Mister God, how do we know he loves us?”

“Them pollywogs, I could love them till I bust, but they wouldn’t know, would they? I’m million times bigger than they are and Mister God is million times bigger than me, so how do I know what Mister God does?”

She was silent for a little while … Then she went on:

“Fynn, Mister God doesn’t love us.” She hesitated. “He doesn’t really, you know, only people can love. I love Bossy (the cat), but Bossy don’t love me. I love the pollywogs, but they don’t love me. I love you, Fynn, and you love me, don’t you? …”

“No,”she went on, “no, he don’t love me, not like you do, it’s different, it’s millions of times bigger.”

“Mister God is different. You see, Fynn, people can only love outside and can only kiss outside, but Mister God can love you right inside, so it’s different. Mister God ain’t like us; we are a little bit like Mister God, but not much yet.”

“You see, Fynn, Mister God is different from us because he can finish things and we can’t. I can’t finish loving you because I shall be dead millions of years before I can finish, but Mister God can finish loving you, and so it’s not the same kind of love, is it? …”

“Fynn, what is the word for when you see it in a different way?”

The narrator explains that the precise phrase she wants is ‘point of view’.

“Fynn, that’s the difference. You see, everybody has got a point of view, but Mister God hasn’t. Mister God has only points to view.”

It seemed to me that she had taken the whole idea of God outside the limitation of time and placed him firmly in the realm of eternity. ‘Points to view’ was a clumsy term. She meant ‘viewing points’.

Mister God had an infinite number of viewing points … Humanity has an infinite number of points of view. God has an infinite number of viewing points. That means that - God is everywhere. I jumped….

“There’s another way that Mister God is different.” We obviously hadn’t finished yet. “Mister God can know things and people from the inside too. We only know them from the outside, don’t we? So you see, Fynn, people can’t talk about Mister God from the outside; you can only talk about Mister God from the inside of him.”

From a practical point of view, if we applied this to meditation we would quickly find that meditation is learning to love and talk to God from the inside. We would understand that the inner form of the Master, the Shabd (which has ‘an infinite number of viewing points’) loves us right inside, and this is different from any external experience of love that we have ever had. We would see that the Shabd Master is everywhere and infinite; he is there when he is not there; we would begin to understand something about the reality of the Master’s actual existence within us, a reality we touch daily through meditation.

Perhaps we would reconsider our actions if we truly believed that the inner Master was viewing all our actions ‘from an infinite number of viewing points’!

Our task, like that of the maidens, is to put in the effort of putting oil in our lamps and trimming the wicks, so that we can wake up to understanding the actuality of the light of God in our lives. The mystics tell us that spiritual understanding is the highest form of consciousness; it goes beyond intellectual knowledge and the constraints of the mind. They explain that knowledge put into daily life and turned into practical experience becomes understanding, and meditation is the tool to achieve this.

The mystics say that doing this is not simply an intellectual exercise. When, like Anna, we begin to grasp the living reality and presence of God, we start to feel a pull and we reach out to the Lord, moved as we are by this yearning.

Baba Ji tells us that the human body is simply a platform from which we reach to the spiritual. Understanding this brings infinite viewing points, which enable us to see beyond our intellect, through the doorway of the third eye to the actuality of the soul, and our reluctance gives way to a sense of our undying relationship to the Shabd Master within.

Something to Think About

Taking on Criticism

To please an official, the American president Abraham Lincoln once signed an order transferring certain regiments. Secretary of War Stanton, convinced that the President had made a serious mistake, refused to carry out the order. And for good measure he added, “Lincoln is a fool!”

When this was reported to Lincoln he said, “If Stanton said I am a fool then I must be one, for he is almost always right. I think I’ll step over and see for myself.”

That is exactly what he did. Stanton convinced him that the order was a mistake and Lincoln promptly withdrew it. Everyone knew that part of Lincoln’s greatness lay in the way he welcomed criticism.

Anthony de Mello, The Heart of the Enlightened

Brother, we should not mind anybody’s criticism at all. I can tell you, critics are the best guide in life. We should always keep our ears and eyes open to our critics…. If it has any weight, we should try to learn from that criticism and try to improve ourselves.

Maharaj Charan Singh, Spiritual Perspectives, Volume III

Book Review

Plotinus or the Simplicity of Vision

By Pierre Hadot. Translated by Michael Chase

Publisher: Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993.

ISBN: 978-0-2263-1194-4

The French philosopher and historian Pierre Hadot has transformed the way we look at ancient philosophy today by uncovering the spiritual kernel in Greco-Roman philosophy. He states as his thesis that:

The greatest lesson which the philosophers of Antiquity - and above all Plotinus - have to teach us is that philosophy is not the complicated, pretentious, and artificial construction of a learned system of discourse, but the transformation of perception and life, which lends inexhaustible meaning to the formula - seemingly so banal - of the love of the Good.

Ever since the Middle Ages, philosophy has been viewed as a kind of learned discourse, often full of incomprehensible jargon. Hadot, who died in 2010, devoted his academic life to reminding academics of philosophy as a way of life and as spiritual practice.

Hadot’s was one of the few voices within academia speaking out in defence of mysticism. As A. I. Davidson writes:

Pierre Hadot is well aware of the fact that the Plotinian journey of the soul is, as often as not, viewed suspiciously nowadays, as though the call to the mystical is a deceptive invitation to mystification…. He … insists that Plotinus’s lived experience was not a means of escape, not a way of evading life but of being absolutely present to it. If we ignore those dimensions of human experience that include the “mysterious, inexpressible and transcendent”, we shall succumb to another kind of mystification, one that is “just as tragic, although more subtle.”

Many of Hadot’s books are written in a style accessible to all, while still upholding the highest standards of precision and rigor. Plotinus or the Simplicity of Vision, Hadot says, was written “from the heart, in a kind of moment of enthusiasm.”

In Plotinus Hadot offers a breathtaking synthesis of the essential spiritual teachings of this third century Roman philosopher. He argues that, to understand Plotinus, one must understand that he is discussing the mystical experience of union with “the One” - a term Plotinus used interchangeably with “the Good” to denote the highest reality. For example, Plotinus describes the soul’s realization:

She says - “It’s him!” - she enunciates this later; for the moment she says it in silence. She is filled with joy,… because she has become once again what she was before, when she was happy. She says she despises… everything which used to give her pleasure. … If everything else round her were to be destroyed, that would be just what she wanted, so that she could be close to him in solitude. Such is the joy to which she has acceded.

Plotinus gave clear directions on how to attain the spiritual dimension: “We must leave behind all sensible hearing, unless it is unavoidable, and keep the soul’s power of perception pure and ready to hear the voices from on high.” As Hadot summarized his instructions, “We must place ourselves in a disposition of calm restfulness, in order to perceive the life of Thought.”

The Greek word nous is a key term in Plotinus’s philosophy. Plotinus describes nous as an ubiquitous divine presence:

It is not the case that it came, in order to be present; rather, if it is not present, it is you who have absented yourself. If you are absent, it is not that you have absented yourself from the All - it continues to be present - but rather that, while still continuing to be present, you have turned towards other things.

He says that nous is rooted in the One or the Good, the essence of which is love and grace, and that its beauty and radiance is beyond words. Nous is usually translated as Spirit or, more often, Intellect:

The Intellect is beautiful; indeed it is the most beautiful of all things. Situated in pure light and pure radiance, it includes within itself the nature of all beings. This beautiful world of ours is but a shadow and an image of this beauty. … It lives a blessed life, and whoever were to see it, and - as is fitting - submerge himself within it, and become One with it, would be seized by awe.

For Plotinus, the Forms (translating the Greek word idea, meaning vision) shape us and everything around us. In the World of Forms all is light, and “the splendour is without end”. Since the World of Forms shapes the material world, Plotinus did not view the material world or the human body as evil; he only saw in them varying degrees of the Good because nothing can exist without some traces of the Good in it. What is evil is our obsessions. Hadot explains:

It is not life within the body which prevents us from being aware of our spiritual life; the former is, as such, unconscious. Rather, it is the concern we have for our bodies. This is the true fall of the soul. We allow ourselves to be absorbed by vain preoccupations and exaggerated worries.

While Plotinus’ essential teaching focused on mystical realization, he was also concerned with the question of how one is to live daily life. After one glimpses life up above, one lives life below as a preparation for contemplation through the practice of the virtues, especially gentleness and compassion. As Hadot describes Plotinus’s teaching:

Attention paid to the Spirit does not exclude attention to other people, to the world, and to the body itself…. Such attention is mildness and gentleness. Once transformed, our vision perceives, shining on all things, the grace that makes God manifest…. Then there is no longer an outside and an inside: only one single light, towards which the soul feels only gentleness: [as Plotinus says,]“The better one is, the more kind he is towards all things and towards mankind.”

Plotinus left no writings. His responses to the questions of disciples, along with spontaneous discourses, were published thirty years after his death under the title Enneads by one of his closest disciples, Porphyry.

Porphyry also wrote a biography of Plotinus. In it he tells us that his teacher took care of orphans entrusted to him by their parents:

Although he was responsible for the cares and concerns of the lives of so many people, he never - as long as he was awake - let slacken his constant tension directed towards the Spirit. He was gentle and always at the disposition of everyone who had any kind of relationship with him. This is why, although he spent twenty-six entire years in Rome, and acted as arbitrator in disputes between many people, he never made a single enemy amongst the politicians.

As Porphyry recalls, those who were fortunate to come in contact with him were transformed:

By the mere presence of his spiritual life, the sage transforms both the lower part of himself and the people who come in contact with him. From one end of reality to the other, the most effective mode of action is pure presence. The Good acts on the Spirit by its mere presence; the Spirit acts on the soul, and soul on the body; all by their presence alone.

Plotinus was an embodiment of the Good for his contemporaries. He had himself acquired the qualities of the Good he described: “The Good is gentle, mild, and very delicate, and always at the disposition of whomever desires it.”

Book reviews express the opinions of the reviewers and not of the publisher.