Download | Print | Archives

July 2014

Longing into Love

What Am I Here For?

Born Thirsty

Home Truths

A fictional exchange of emails …

Feeling Funny

Something to Think About

What Is a Spiritual Life?

Here’s Looking at You

A Traveller’s Guide

Because I Cannot Sleep

Practical Help

All You Can Give

A Jug of Water

Facing Death Calmly: Drawing Inspiration from Socrates

Book Review

The Other Buddhism: Amida Comes West …

Start scrolling the issue:

Longing into Love

Sometimes when I look at you, I feel I’m gazing at a distant star.…

It’s dazzling, but the light is from tens of thousands of years ago.

Maybe the star doesn’t even exist any more. Yet sometimes that light

seems more real to me than anything.

Haruki Murakami, South of the Border, West of the Sun

That sense of longing for something intangible – something that can seem unreachable – is part of what it is to be human. The pain of this longing can drive us to seek solace in worldly satisfactions. But they will never fill our emptiness, for they are not what we really want.

That thirst we have is, rather, for something higher, something spiritual – and to deny it is to deny our humanity. Instead, as the articles in this issue of Spiritual Link remind us, we must focus on identifying and living in accordance with our true purpose here.

Fortunately, the Masters have shown us what we need to do to live a spiritual life. And it is something anyone can do. We just need to keep life simple, put our trust in the Master, and follow his advice. It’s about doing, not thinking; action, not endless preparation.

But even though we know what we must do, our effort can become weak and our meditation slack. We may let our spiritual life become empty and routine. If this happens, it’s time to take a close look at ourselves, and remember what we are here for.

Most of all, we must not forget how much the Master is giving us. He loves us beyond all understanding, however little we can give him in return. What counts is not what we achieve but how hard we try. So let’s give everything we can. Let’s turn that longing into real love. For those who have love, nothing else matters.

What Am I Here For?

As my sister and I prepared to depart for university, we awaited with some dread the predicted lecture from our dad: the lengthy talk about honouring the family name and focusing on our studies, avoiding temptations and keeping regular hours, and above all doing our very best.

To our great surprise, on the morning of our departure for college he simply gave us each a sealed envelope, which we were instructed not to open until we reached our university residences far from home.

Setting off on the journey naturally produced bittersweet emotions. On the one hand, leaving the comforts of home and all the guidance and love of our parents’ shelter was heartbreaking. On the other hand, we were excited by the prospect of new adventures and experiences.

When I reached my college room, I was eager to open the envelope. Inside was but a little card, bearing in bold letters the following five words: WHAT AM I HERE FOR? Just a simple rhetorical question. The card was to be placed on the study wall above the desk, and so it was. Job done.

Initially this seemed a very simple and straightforward thing to do. But boy, oh boy, did this card come to life!

Whenever tiredness crept in and sleep seemed preferable to studying, the card would leap into view and shock my heavy eyelids to flick back up. When worldly temptations pulled too strongly, its message revived my balance and focus. If ever morals might be about to waver, the words it bore provided guidance.

This card acted as a parent’s watchful eye, a summary of spiritual values, and an invitation to remembrance of God. In a way, it built an invisible fence of principled living around my daily college life.

Thankfully, the many years of studying were safely completed. However, the message on the card had not finished its job. As time went by and the card stayed with me, it took me into layers of spiritual searching deeper than I had been inclined to explore during my college years.

It brought on an existential questioning and a pondering on the deeper meaning of life. This eventually led to a strengthened yearning for God, which culminated at last in initiation and receiving the great gift of Nam.

The card bearing that question ‘What am I here for?’ lives nowadays beside my bed. Whenever the tendency arises to slacken on the path or to be carried away by the world, that battered old piece of card jolts me back into focus.

The present Master is always encouraging us to seek more meaning in whatever we do. He also tirelessly reminds us to give real focus and attention to our meditation, rather than letting it become a mere ritual. In fact, we should be attentive to whatever we are doing, and be present and focused in the moment. Somehow, the card my father gave me still serves to reinforce this message from the Master.

‘What am I here for?’ is the ultimate question for all of us. Musing upon it helps us identify our priorities and focus on what is most important to us. It makes us aware of the fleetingness of time and of the things in our lives that can steal our time. In this way, it helps us adjust our daily schedule around our realigned priorities. Ultimately, it enables us to bring more alertness to our meditation and to carry that love and light into our daily life.

As Guru Arjun Dev says:

He who cherishes the Word within his heart, the greatest king is he;

he who has Nam within his heart will fulfil the purpose of his life.

As quoted by Maharaj Charan Singh in Divine Light

Born Thirsty

We are all born into this world thirsty: we come into this creation needing to drink in order to survive. All living things need water, and the earth is unique in our known universe because it has that water which enables life to survive here. A human being cannot exist very long at all without water, so nature has given us a craving to take in the vital fluid we need. Without that thirst we wouldn’t want to drink.

We can try to quench our thirst with other forms of liquid, such as milk, fruit and vegetable juice, and man-made concoctions like fizzy or fermented drinks. But it is the water contained in them that provides their main benefit. And although we have grown to enjoy these other drinks, we know it would be bad for our health to rely on these alone.

Spiritual thirst

In the same way that our bodies have been given thirst in order to make them seek the water they need to survive and flourish in this creation, our souls have been given a kind of thirst too. We all need love and nurturing, and receive it to varying degrees, from our parents, our families, our communities, our friends. But even those who have love in abundance often feel a thirst for something higher. This thirst is for something which, no matter how hard we try, we cannot satisfy in the world around us.

We try to quench our soul’s thirst by every possible means known to us: through people, through our families and friends, boyfriends or girlfriends and spouses; through our activities, whether work, hobbies, social or political deeds. But still our spiritual thirst is not quenched. We plan, we work, and we keep ourselves busy, going from one activity to the next, one person to the next, trying to quench this powerful thirst within us. What we are thirsting for is the realization of our true nature and the rediscovery of our original source.

Why do you drink water, O swan soul? There is an ocean of nectar within you, which you can drink just by withdrawing your consciousness inside.

Soami Ji Maharaj, Sar Bachan Poetry

The soul’s thirst cannot be quenched by any water of the world. Perhaps here Soami Ji is equating water with the things of this world: bodily considerations, concerns of the mind, and outer observances such as rites and rituals. We can never hope to quench our spiritual thirst through any of these. Even the observances of religion are meant only to point us in the direction of this inner nectar. They are there to provide us with inspiration to find it, and all of our holy scriptures sing its praises. Maulana Rum says: “Young lovers like to drink wine and sing love songs. There is another wine, another song, another tavern.”

The divine nectar

Soami Ji lovingly tells us that there is a divine nectar for the soul to drink, an ocean of nectar – a limitless supply that is just there inside us, which will quench the thirst of the soul. This is the divine nectar, the elixir of life, The Name of God, the Anahad Bani, the living water, which all saints and mystics tell us about, using different languages. This is a nectar that not only satisfies the soul’s thirst but also intoxicates our whole being. Kabir tells us that, “Those who drink the elixir of the Lord’s Name do not suffer the pangs of thirst again.”

And Guru Ravidas, in the same vein, writes:

I drank, indeed, I drank the nectar of God’s love … drinking this nectar, ‘me’ and the world are forgotten, and I get intoxicated with the divine elixir.

Quoted in Guru Ravidas, The Philosopher’s Stone

It is virtually impossible to describe this nectar, this Anahad Shabd, this Nam – just as it is impossible adequately to describe being in love. Despite the attempts of poets through the ages, true love can never be explained in words.

Just what the sound current is may not be so easy to tell. It is the Creator himself reaching down into the realms of mind and matter in a perpetual stream of his own divine spirituality.

Introduction to Sar Bachan

The waves of the ocean of Shabd are surging in each one of us. Those who drink of its waters are no longer troubled by thirst or hunger and gain eternal life. This was the water of life that Christ offered to the woman of Sychar at the well so that by drinking it she might quench her thirst forever.

Maharaj Sawan Singh, Philosophy of the Masters, Vol IV

We have to force the mind to drink

In the beginning stages of meditation, when we attend to our bhajan, we have to force our minds to drink of the nectar. This is because the mind has great difficulty in letting go of the world, as it is tied to the senses. It is like the horse whose rider is trying to bring him to the watering hole to drink: the water wheel makes such a noise that the horse refuses to go near. When the water wheel stops, there is no noise but the water too stops flowing. When the wheel turns, the noise is there and so the horse is afraid and won’t drink. Finally, the rider has to whip the horse and make him go despite the noise of the wheel.

So too we have to force the mind to drink from that well within us, surrounded by the noise of the world and our minds. The world will go on, the mind will go on – still we want to drink, we need to drink. That Shabd, that living water, is vibrating and shining every second of every day. The Master has led us to the watering hole. It is up to us to make the effort, to whip the mind, with our love and devotion, and attend to our meditation.

Becoming a receptacle

To take in that nectar that will quench our spiritual thirst, we first need to become receptive. We cannot just reach out and grasp water – if we try, it runs through our fingers. We have to make our hands into a cup shape. Similarly, we ourselves have to become receptacles – we have to stop grasping and reshape ourselves so that we can receive the divine nectar.

Philo Judaeus writes in On Dreams:

And when the happy soul stretches forth its own inner being as a most holy drinking vessel – who is it that pours forth the sacred measures of true joy but the Logos, the cup-bearer of God and Master of the feast – he who differs not from the draught he pours – his own self free from all dilution, who is the delight, the sweetness, the forth pouring, the good cheer, the ambrosial drug… whose medicine gives joy and happiness.

We are the cup, the vessel. And we must choose what we would prefer to be filled with – poisons of the world or the nectar of Nam. At present we are drinking the wrong things. Maharaj Charan Singh often used the example of an upside-down cup – we can never expect it to be filled with rain water, no matter how much rain falls. That nectar is always raining down within, but so long as the cup of our mind is facing downwards it cannot be filled.

What we are looking for is right here

That ocean of nectar is right here within us, and the Master is ready to help us quench our longing, yet we are wandering around in the world mad with thirst.

Water is everywhere around you, but you only see barriers that keep you from water. The horse is beneath the rider’s thighs, and still he asks, Where’s my horse? “Right there under you!” Yes, this is a horse, but where’s the horse? “Can’t you see?” Yes, I can see, but whoever saw such a horse. Mad with thirst, he can’t drink from the stream running so close to his face. He’s like a pearl on the deep bottom, wondering, inside the shell, “Where’s the Ocean?”

Rumi, This Longing, translated Barks & Moyne

Maybe now we have not yet heard the highest Shabd; maybe we are still at the beginning. But we definitely feel that living stream resounding within us. It manifests as love in our hearts, as forgiveness towards each other. When we love unselfishly, that is Shabd; when we forgive each other, that is Shabd. That nectar streams through us as devotion, as determination to reach our goal, as love for the teachings: this is all the Shabd. In the Master’s presence we often feel this powerfully.

Nam courses through our veins; it is our blood, our life-force. That spiritual thirst we feel drives us towards our goal, parched and often desperate as we stumble through the desert of the world. Meditation is the action we take that will finally begin to alleviate our thirst.

Home Truths

A fictional exchange of emails

From: [email protected]

To: [email protected]

Hi Sarge!

How are you doing out there in the wilds? Mum and Dad are also wondering how things are for you. Mum says does Sonia like the new house? It must be great to have your own place.

Hear from you soon I hope – Sanjeev

From: [email protected]

Hi Sanjeev,

We certainly feel far away, that’s for sure. We’re surrounded by hills instead of houses! Yesterday, Sunday, it was really weird not to be dragged out of bed by Dad and told to go to satsang. To be honest, we hardly know what to do with ourselves, though I would never have guessed I’d be saying that. I’ve been thinking quite a lot about Sant Mat recently. I wish I’d talked to you about it while I had the chance. How do you manage to make it your ‘own’ when you’ve grown up with it? How did it feel getting initiated?

Anyway, got to go now and collect Sonia who has been checking out the local shops – Yours, Sarge

From: [email protected]

Getting initiated was good. What do you mean by ‘your own’?

From: [email protected]

I mean (and I know this sounds bad) that I feel I’ve spent most of my life resisting Mum and Dad rather than believing in Sant Mat. Well – that’s not strictly true, I DO believe it but some things just don’t add up for me. Like, we’re told not to follow rituals but it seems to me that going to satsang is a ritual. Also, the point of being a satsangi is to do meditation but I know Mum doesn’t do it every day of her life. Probably this is something that I didn’t find the words to say when I was at home. Now that I’m missing home, I’m thinking about the things that didn’t stack up.

From: [email protected]

Dear Sarge,

Satsang is just so that we can remember the Master and the teachings. That’s all it’s there for. Parents get their kids to do all sorts of things that will be useful to them in later life, which the kids don’t appreciate at the time – going to school, doing chores, keeping clean. The parents know it’s useful even if the kid doesn’t. Look at yourself – the reason that you know about Sant Mat is because our parents took the trouble to take us to satsang. Do you think Dad thought it was a ritual? I think he’s a very passionate satsangi. As for Mum, you know that her health’s always up and down. And besides, why are you expecting initiates to be perfect? We get initiated because we’re not perfect – and that includes Mum and Dad – and then we have to struggle to do what’s expected of us and live up to it all. When I decided to ask for Nam, Uncle Ji (the Secretary) told me to look to Baba Ji only. That was the best advice I ever had. Ignore what other people do and don’t do. Your own relationship with the Master is all that counts. Anyway, keep thinking …

From: [email protected]

It’s all very well to make excuses by saying that no one’s perfect, but surely there should be a difference between satsangis’ behaviour and people who don’t have the benefit of the teachings? Take our cousin Lilli. When she wanted to get married to that guy her family didn’t approve of, they were really unpleasant about it. I’m glad Lilli’s happily settled now, but it’s no thanks to them. There was talk about his being the wrong caste and, say what you like, I KNOW that doesn’t fit with Sant Mat which says that we have to go right beyond caste and creed. Yours from the wilds (physically and mentally) – Sarge

From: [email protected]

Okay, so you or I wouldn’t join in that unpleasantness because we’re a different generation. But don’t think that because caste and creed may not be an issue with us, we may not fall into other traps which are equally at odds with the purity of Sant Mat. Look, I’ll say it again: it’s a struggle. Stop judging others. Instead of asking other people to live up to your expectations, see whether you can do it yourself. I remember a conversation you had with Mum when you told her you were moving north. She said you wouldn’t like it there. And you said you were “a big enough boy” to be able to pick out what you wanted and leave the rest. Surely that’s how we ought to be with Sant Mat? Shouldn’t we be able to realize the jewel that is the Master, and recognise that what others do or don’t do isn’t our concern?

From: [email protected]

Now you’re making me feel bad. Where’s the nearest satsang to here?

From: [email protected]

Sarge, it’s only fifty miles. Get on your bike!

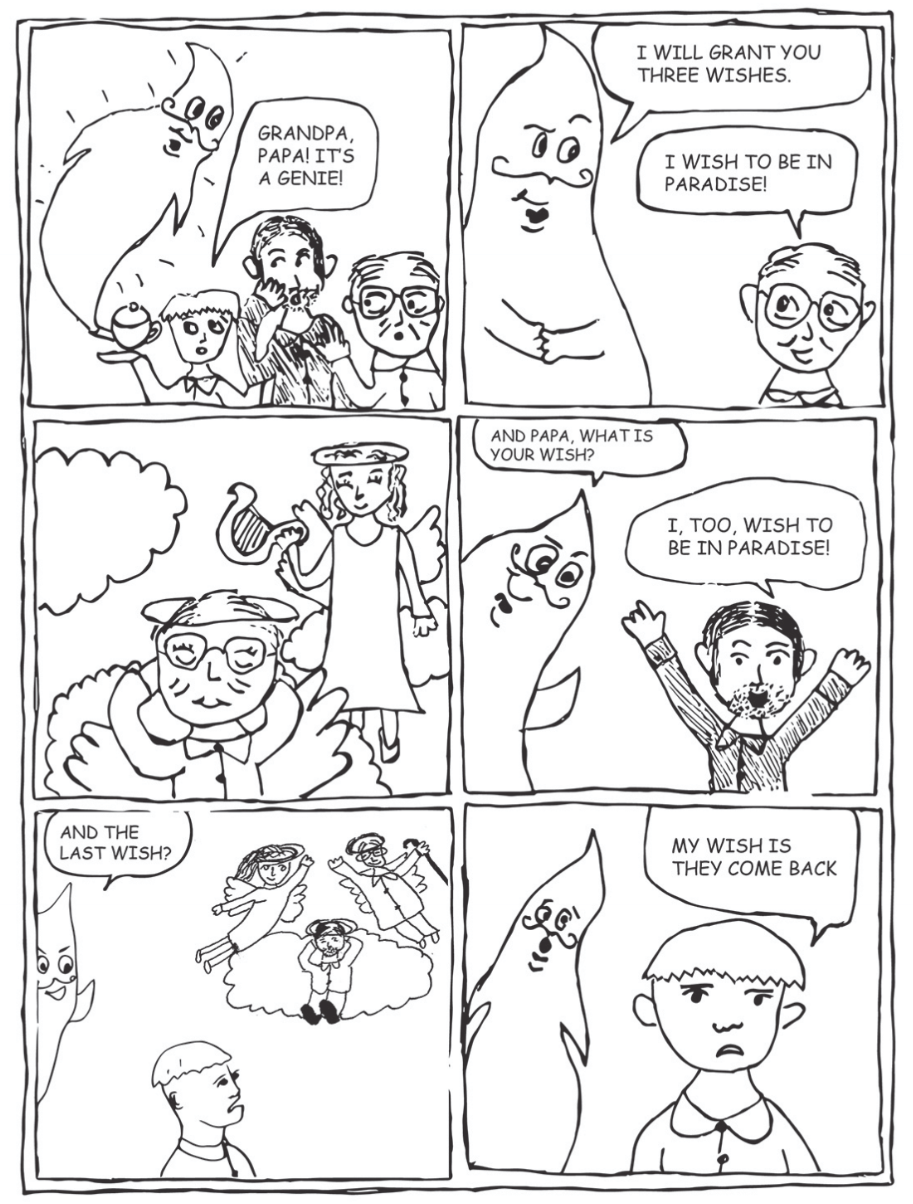

Feeling Funny

Three Wishes

Something to Think About

Where My Love Is

A loved one said to her lover

“O youth, thou hast seen many cities abroad.

Which of them, then, is the fairest?”

He replied, “The city where my sweetheart dwells.”

Wherever the carpet is spread for our King,

’tis a spacious plain though it be narrow as the eye of a needle.

Wherever there is a Joseph beautiful as the moon,

’tis Paradise, even if it be the bottom of a well.

Rumi, Masnavi, Book III

A certain village received a visit from a holy man and there was great excitement when he announced that he would take all those who came to him to heaven. The assembly was packed as the villagers flocked to him – all except a young man who was well known for his devotion. When this was brought to the attention of the holy man, he sent for the youngster and after greeting him kindly, asked him: “Only you have stayed away. Why is that?”

The young man humbly replied: “Well, I have a guru but I don’t know where he dwells. If you take me to heaven and he is not there, that will be hell for me. Please leave me here because even hell will be heaven if he remains.”

Traditional story

What Is a Spiritual Life?

Who am I, why am I here, what is the meaning of life? What is a spiritual life? Many people have given up asking such questions, as if perhaps there is no answer; or, if there is an answer, it’s not necessary to know it. And how absurd is that? How can we have clear life goals if we do not know what we are here for – and where we might be going when the time comes to leave?

Of course, it can seem easier not to know what it means to live a spiritual life, because not knowing means we do not have to change anything in our lives. Some of us are subconsciously afraid that knowing the answer might mean a change to our present lifestyle. Even though many of us are not happy with our present state, we fear a change might be for the worse.

Yet we all know what it is to say, “I know this is right and it doesn’t matter what anyone says; this is what I’ve got to do.” Even when such a conviction seems to defy logic, we know when it is true for us. Wisdom requires only clarity of thought, not intellectual prowess. While knowledge is constructed by the mind, wisdom comes from deeper within and is a revelation of our real self. For this reason, wisdom is always very simple.

Knowledge can be complex but wisdom is always simple

Many wise people have very little intellectual knowledge. It has often been said that the greatest truths are the simplest and so are the greatest men and women. Yet we tend to assume that the most important of all questions must have the most complex answers – and probably ones we don’t understand. Meanwhile, we are continually missing the simple truths that the mystics keep repeating.

Imagine for a moment that you were the Creator. Would you have made it so difficult to find the meaning of a spiritual life that someone would have to renounce all attachments and travel on a sacred pilgrimage for many years until, finally arriving in cold mountains, a holy teacher in a dark cave would unveil life’s meaning? Or would you make it so simple that the answer would be sitting right in front of them, waiting for the child in them to see it?

The saints tell us that the Creator gave us this human life for only one purpose, and that it is to bring to an end our repeated rebirths into this world. Can it be any simpler than that? We have not come to this present birth to face the challenge of improving our personalities, building our stamina, or increasing our knowledge and experience, but rather simply to say goodbye once and for all.

It’s all about saying goodbye

This is the simple truth: the spiritual life is all about saying goodbye. But, after being in this creation for eons, how do we go about that? Well, first of all, let us look to the Master. He provides a living example of how to lead a spiritual life, saying goodbye to everyone and everything here. He does many of the same things that we do: he eats, sleeps, works, spends time with his family and attends to his responsibilities. But he does one more thing all twenty-four hours of the day: he remains aware of the divine spirit within – even when tying a shoelace. That connection with the Shabd within can be ours too, if we follow the Master’s guidance (and his example) on how to reach it.

Mystics down the ages have been telling us one very simple fact: they advise us to be rather than to try to become. Within these two words, being and becoming, our whole life is contained. Being is the nature of the soul, which is enlightenment; becoming is the nature of the mind, which is confusion and ignorance.

Our destiny is to be one with the Lord. In fact, we already are, but we cannot yet see it. The Master, through our meditation, is removing the coverings of the soul and prying us free, so that after many ages we can finally realize our true identity. It is only by diligent daily meditation practice that we will slowly come to realize who we really are.

To this end, the Master asks that we give at least one tenth of our day to meditation. In the furious rush of this world, we’re asked simply to sit still and stop thinking. This little request from the Master goes against everything this world stands for, but that is because it is the way out of the world, out of all its pain and suffering.

Meditation comes first

Medieval mystic Meister Eckhart writes that we have been in motion throughout time. We are tired and want to stop; we want to go home, to rest. The end of all motion is rest; the only rest is that which has no beginning, no end, no motion -and that is the Divine Light. Master is offering us that final rest. Once he takes us into the orbit of his divine embrace, we begin to understand that we have no choice but to come to him.

To live the spiritual life, we must organize our days around our meditation. Our decisions on how to balance work, sleep, and leisure will be based upon the commitment we need to bring to spirituality. If we are not fully committed to our meditation practice, then the mind has trapped us, tricking us into a meaningless ritual.

But it’s not an easy journey, because it’s not a road we are familiar with. If we are disappointed that we haven’t attained what we had hoped for, or that meditation feels a hundred times more difficult than we expected, we need to remind the mind that we are travelling not on a path of this world but on a path that takes us out of this world. Maharaj Charan Singh has said we should never feel we are back where we were a dozen or so years ago: there is no going back. Meditation, once done, can never be undone, whatever its quality or quantity.

The Master is taking us towards our long-forgotten home. So it behoves us to carry on taking small steps forward, to convince the mind of the importance of the spiritual life, and to keep faith with our Master. When difficult things happen in our lives, we must trust in the Master and accept that he will never allow anything to come our way that will not benefit us spiritually in the long run.

Just trust in the Master

When the Master initiated us, he took charge of our spiritual life and told us that if we attend to our meditation, as best as we can, he will take care of everything. When we put into practice his instructions, then our limited faith begins to grow firmer. Whatever our Master asks us to do always leads to the shortest path to salvation. He does not want us to be here one second longer than necessary. In fact, his own seva is not complete until all his disciples reach Sach Khand.

When we live like this – putting our full trust in him – we begin to see how great has been our ignorance of Master’s love for us. In the end, it is only his love, not our meditation, which is going to relieve us from this physical life of suffering. But the Master has asked us to work in partnership with him, and this means that we must exert ourselves to escape our habit of compulsive thinking. Any thought about the future is imagination. Any thought about the past is memory, probably faulty at that. There is no reality to thoughts, at the spiritual level.

What helps is simran, the divine names given us by the Master which carry the power to stop thought and bring the mind to the here and now of the eye focus. Turning towards him through simran allows us to give up worrying about what is happening in our lives. Simran enables us to forget ourselves completely and remember the Master, because simran leads us to the Master, to Shabd, to limitless love. It is a gift from the Master to enable us to be with him at the spiritual level, at any time. Simran has even been called the soul’s life support system.

The objective of the spiritual life is to go beyond the limited to the unlimited, beyond the ego to the realization of the true self. How can the limited mind understand the unlimited soul? Someone once asked Mrs Albert Einstein if she understood her husband’s famously complicated theory of relativity. She replied that no, she didn’t, but he was her husband so she trusted him in his work. In spirituality our intellect fails miserably – so how are we to comprehend all of this? Well, with the mind, we certainly cannot. But when we learn to trust the Master and realize the mind’s ignorance, we will find ourselves engulfed in divine reality.

Most of the time, we try to cure our pain from the outside; but when we are aware of the truth and living a spiritual life, we fight instead to go within. And when we go within, life can be magnificent. Inside, the spiritual light is shining. Any day, any time, we can tune in and experience it. It just seems so silly not to try.

It seems to me we can never give up longing and wishing while we are thoroughly alive. There are certain things we feel to be beautiful and good, and we must hunger after them.

George Eliot, The Mill on the Floss

Here’s Looking at You

The first step towards God-realization is self-realization. If we really want to know God, we must first know ourselves. The truth is, we are afraid to know ourselves – we’re afraid to even look! The acute awareness of our shortcomings that the Master’s presence often brings can make us very uncomfortable. The brighter the light, the more we see the dirt. And that is why the bright light can be painful – it makes us truly see ourselves, and we can feel so ashamed. When people are ashamed, they want to look away. But the saints tell us that becoming aware of our shortcomings is where the transformation begins.

Maulana Rum says:

An empty mirror and your worst destructive habits,

When they are held up to each other,

That’s when the real making begins.

That’s what art and craft are.…There is nothing worse than thinking you are well enough.

More than anything, self-complacency blocks the workmanship.

Put your vileness up to a mirror and weep.

Get that self-satisfaction flowing out of you!

Coleman Barks, Delicious Laughter

We must learn to be extremely honest with ourselves. As Maharaj Sawan Singh says in Spiritual Gems:

Character is the foundation upon which rises the spiritual edifice. As long as one is a slave of the senses, talk of spirituality is a mockery. A magnet would attract shining iron, but not rust. Similarly, the Sound will attract a pure mind, which is free from passion’s dross. But when the mind is steeped in the mud of passion and desire, it is like iron that is covered with rust and mud. The first essential step to a spiritual life is character. One may deceive one’s friends, relatives and even oneself, but the power within is not deceived. It is the duty of a devotee to keep constant watch over his mind and never let it loose. As a mother looks after her child, so does a true devotee watch his mind.

In order to keep watch over our mind, we have to look at it. Fortunately, we are given ample opportunity to know the state of our character throughout our life. Each situation can be looked at like a little test. How can we know that we are impatient if we don’t find ourselves in an irritating situation? How can we know that we are lustful if we don’t ever mix with people, some of whom might be very attractive or appealing? How can we know the extent of our ego and pride unless we are challenged by praise or disapproval?

When we find ourselves in positions of authority but remain humble; when we meet a beautiful woman or man but remain chaste in thought and deed; when we are confronted with luxury and extravagance but remain content with our own lot; when somebody insults us or challenges our views but we remain calm and loving – then we know we are learning to gain mastery over ourselves, that our character is being strengthened and we are being cleansed.

However, we should try not to put ourselves in situations that will influence us negatively. The Masters don’t recommend that we live in caves as recluses, but they do suggest that we try to live a wholesome life, because we absorb the atmosphere created by the company we keep. If we attend to our meditation regularly and diligently, if we live according to the principles of spirituality, we will have the strength to go through our allotment of karmic experiences with a sense of balance.

When we look at a seed it is only the outside shell that we see, but with understanding and experience we can envisage the life that lies latent in the seed. So too, when we start to look at ourselves we see the outer covering, for better and for worse. Through meditation and the grace of the Master, we become conscious of our inner potential. And all our failures, both small and great, will serve to help keep us humble. Each day is an opportunity, and he will never give us more than we can take.

Like the seed, we have to break open to release the spirit within. In order for the sculpture to emerge, the stone must be chiselled. Without the sculptor’s work it would remain a block of stone. It took the power of Michelangelo’s arm, and his vision, to create the statue of David. If the stone could have begged “Do not break me”, where would the art be? Look at God’s miraculous creation – are we not part of his artistry?

Look for where the light catches

To see the imperfections of the wood when we are trying to sand it smooth, we tilt our head to see where the light catches, and then we know where to sand. When we paint, we have to look at the wall from a different angle, to see where we have missed any spots. Each situation allows us to find the imperfections in ourselves. Each person in our life is a grinding stone for us; each situation a blank wall to cover with our love, the Master’s love that is developing within us. We just need to change our perspective ever so slightly, to see where we have missed a spot, to see where the surface needs sanding.

We cannot change our perspective without meditation, without attempting to do our meditation. We may be flawed by imperfections, past transgressions, weaknesses and sin. But we don’t need to try to hide these from ourselves, or from the Lord. He is everywhere. He is in us. He is us. We should bravely face our weaknesses through meditation and place our trust in the Lord’s power, mercy and grace.

Despite our imperfections and failings we are drawn to the Lord. As we look at him, as his love enables us to forget our sins and failings, we forget ourselves. The moth sees only the light; it does not think about itself or the other moths at all. It does not consider its unworthiness. It cannot do other than simply fly. As we get purer, as we put in the effort, as we fall and get up again, we cannot do other than simply run towards the Lord.

His love overrides all our imperfections and failings. At the end of the day, we are his! Our sins are many, but his mercy and grace are greater. Some disciples have even affectionately expressed the sentiment that the Lord would not be able to show his greatness if we were not in such a poor state. Tukaram says:

Had I not been a sinner in this world, my Lord,

How couldst Thou be known as the Redeemer?

Hence, my name as ‘the sinner’ comes first.

Then comes Thine, O Fountain of Mercy.

The Philosopher’s Stone owes its glory to iron,

Else a common stone only it would be.

It’s the beggar’s appeal, O Tuka,

That lends prestige to the wish-granting tree.

Tukaram, Saint of Maharashtra

The love of the Lord is ultimately what will rescue us from our sorry state. However, just as parents must show their children not only affection but also discipline if they are to help them learn to find a positive way forward in the world, so too we sometimes feel the Lord’s loving and sometimes his discipline. Just as our children have to learn self-discipline to stand on their own two feet in the world, going through so many experiences, learning which behaviours bring positive or negative results, so too we need to develop self-discipline as we grow towards spiritual maturity.

Although the Master tells us we should not indulge in excessive analysis, a little introspection now and then will enable us to improve. When we learn to play a piece of music, we have to practise the difficult bits. If we only play the easy parts of a piece, we will never be able to play the whole piece. The key is first to identify what the hard parts are. Which note is difficult to play? Which transition? Once we are aware of what causes the problem, we can practise overcoming that difficulty over and over, until our muscles remember exactly how the hand needs to move. If we just gave up at that difficulty, how would we ever discover the beauty of the music? Let’s practise the difficult bits!

A Traveller’s Guide

Even though we know that it is effort, and not results, that matters, we may sometimes feel disappointed at what we see as a lack of progress in our meditation. In this case, anyone who feels in need of a little reassurance about their inner journey could try reading the following light-hearted travel guide. Of course, it’s all in jest!

Friend, congratulations on your inner progress! What? You don’t think you’ve made much? Think again! You are sure to recognize the following descriptions of some waypoints along the journey. The ways in which we can overcome the ego by ascending through the inner realms are not as obvious as you might assume. And after all, we cannot miss the chance to take advantage of this opportunity. So travel with me, as I guide you along – and remember, each of the five stages is associated with certain experiences and a unique spiritual sound. Okay, let’s go!

The first stage is called Andhakar in Indian languages. This roughly translates into English as ‘darkness’. But it is no ordinary darkness. It is not just that one observes no light when the eyes are closed. It is that everything in life looks dark and dim, including the hope of ever reaching those wonderful mansions promised by the perfect Masters. This stage is characterized by tremendous restlessness, both of mind and body. The sound of this region is like that heard in a storm – there is a storm in every part of the mind, and this is extended to the body too, including the rustling sounds of the clothing and cushions that one constantly adjusts in order to get comfortable.

The second stage is called Ghor Andhakar, which roughly translates as ‘pitch darkness’. It is characterized by a concentration on the clock sitting next to you, and so the associated sound is the ticking of this clock. A poet has described how, while time flies by, it is the moment that stands still. Like this poet, one wonders during this second stage along the inner journey why the clock has not been chiming its regular half-hour signals and is so still. Frequent efforts are made to check if its battery has gone dead.

Then, the third stage. Just as the moment seems to have achieved absolute stillness, suddenly we enter (needless to add, with his grace) a different level of consciousness – a zone of timelessness. It is at this point that one is transported inwards and loses all awareness of the external world. This third stage promises to be a truly wonderful experience, where painful consciousness of the apparently unmoving clock is replaced by unimaginable peace and quiet. The body becomes absolutely still, and the mind is also at rest. All mystics tell us that this is what happens when the disciple reaches the eye centre, but it is also true that one does not have to go all the way up to the eye centre to experience this sense of peace and tranquility; the throat centre will do. This third stage is called Nidra in Sanskrit, which roughly translates as ‘sleep’. The associated sound is akin to that of heavy breathing.

The fourth stage is a real out-of-body experience. One is no longer conscious of the physical body, but travels out of it and goes through experiences of a non-physical nature which are vividly remembered even after one’s eventual return to the physical body. During these experiences, one sometimes meets dead relatives and friends. In fact, one even encounters those still living in this world, but in a different body – more subtle, less subject to the constraints of time and space. Once in a while, even the Master can be seen in this subtle form during this state. This stage is called Swapna in Sanskrit, which roughly translates as ‘dream’ in English. There is an associated sound called ‘talking in one’s sleep’.

The sound of the fifth stage is very powerful. Everyone hears the reverberations of this inner sound when the disciple is immersed in this state. Some even complain of having been disturbed by it, because the vibrations that emanate from the disciple are so powerful. This state has the difficult-to-pronounce name Kharratte in Indian languages; in English it roughly translates as ‘snoring’.

It must be said that one does not have to go through the first two stages in order to enter the third – one could slide directly into the third, and experience that bliss of a still body and mind, almost invariably followed by the out-of-body experiences associated with the fourth stage. As the saints have said while distinguishing the higher forms of yoga from the lower ones, if we are halfway up a mountain it is pointless to go all the way down in order to reach the top; we can straightaway proceed upwards, skipping the lower stages.

Many of us, indeed, do not bother with the first two, lower stages but just immerse ourselves immediately in the bliss of the third, fourth and fifth. We have been told we should try to devote one-tenth of the day, that is, two and a half hours, to our spiritual practice. But this experience is so sublime that you may want to devote one third of the day, that is, a full eight hours, to these spiritual exercises! I, for one always make sure not to let a single day pass without experiencing the bliss of these last three higher regions.

What good disciples we are!

Because I Cannot Sleep

Because I cannot sleep

I make music at night.

I am troubled by the one

whose face has the colour of spring flowers.

I have neither sleep nor patience,

neither a good reputation nor disgrace.A thousand robes of wisdom are gone.

All my good manners have moved a thousand miles away.The heart and the mind are left angry with each other.

The stars and the moon are envious of each other.

Because of this alienation the physical universe

is getting tighter and tighter.The moon says, ‘How long will I remain

suspended without a sun?’

Without Love’s jewel inside of me,

let the bazaar of my existence be destroyed stone by stone.

O Love, You who have been called by a thousand names,

You who give culture to a thousand cultures,

You who are faceless but have a thousand faces,

O Love, You who shape the faces,

Of Turks, Europeans and Zanzibaris,

give me a glass from Your bottle,

or a handful of bheng from Your branch.

Rumi, as quoted in The Rumi Collection edited by Kabir Helminski

Practical Help

The Masters are very practical people. They give us the highest ideals and then are there at every step of the way, both to explain those ideals and to help us reach them. As an example, let’s consider the following question put by a satsangi to Maharaj Charan Singh and his characteristic answer, as recorded in Die to Live.

Q. Maharaj Ji, it is often said that we should do more meditation with punctuality, regularity, and love and devotion. But love and devotion seem to be out of our hands.

A. Sister, by love and devotion I mean that you must have faith in the path which you are following, that this is the path which goes back to our destination, and faith in the one who has put you on the path.… Faith doesn’t take you to the destination. Practice will take you to the destination, but faith will make you practise … love and devotion is to have faith in the path and the Master. Then we practise also, and then we get the results from that practice.

His words make us realize that there is no need for us to harbour an idea of love as a warm and fuzzy feeling – or, for that matter, as an intense and passionate feeling – and think we are lacking if we do not feel that way. The Master immediately translates the concept of love and devotion into the practical issue of a faith that leads us to practice. At once we see that it is not something unattainable; it is realizable by us, now. Perhaps the ultimate love and devotion cannot readily be known or described, but the first steps towards it are within our capabilities.

If we demonstrate that we value this spiritual path, and give our utmost to it, the Master will help no matter what the odds against us. This reminds me of a documentary film I saw recently about the army. A number of soldiers had applied for transfer to an elite corps and were being put through their paces. On one exercise, they had to complete an arduous trek, bearing heavy packs across rough ground, and then run up a long mountain path to the finish. The soldiers were near collapse at times but the sergeants ran alongside, shouting, cursing and insulting them as only army sergeants can – all with the intention of keeping them moving so that they would pass the test.

To fall is not to fail

The last soldier was clearly in difficulties. He fell repeatedly, struggled to his feet, and fell again, yet still he continued. Were he not to reach the finish line, he would be rejected – and about a hundred yards from the end he collapsed, completely spent. The two sergeants, who until then had been roundly cursing him, went to him and lifted him up, supporting him against their shoulders, then ran with him, his feet dragging on the ground, until he was across the finish line. This soldier was accepted whilst some of the others who had finished earlier were rejected. The examiners were looking for effort, dedication and determination. The soldier had given everything he had to give, and this was why he passed, even though technically he did not even finish the course.

That is exactly our own situation. The Master does not swear and curse of course, but he does run alongside us to encourage and urge us onward – sometimes in a way that can feel stern and uncompromising. He is watching for our best effort and he will use any excuse to help us. As in that story of the two sergeants, if he sees us struggling, he will come to our aid.

Maharaj Charan Singh wrote in Divine Light:

It is better if we finish our internal journey or at least make a good start in our lifetime. But if we are not able to accomplish that and have tried to the best of our ability, we need not be born again on this earth plane to finish it. By his grace the Master most often takes the soul to Trikuti, keeps it out of the reach of Kal, and there enables the soul to accomplish its unfinished task. But our effort should be to take full advantage of this human body and thus finish as much of our journey as possible.

We tend to get hung up on success and failure, but we are judging by the wrong criteria. Soichiro Honda, the founder of the motorcycle and car maker Honda, understood failure. He surprised contemporaries with his remark, “The most valuable product is what we call failure.” He recognized that to achieve anything worthwhile – in his case, innovation – one had to make a huge investment of time and resources, much of which might not produce any recognisable results. In other words, most of your effort is likely to result in apparent failure, but this failure is valuable. First of all, we learn much from our failures. Furthermore, without the effort that produced the failure you would not have achieved anything at all.

To be afraid of failure is a crushingly negative approach to a problem – or even to life itself. So-called ‘failure’ is part and parcel of eventual success – and so it is with Sant Mat. The Masters do not talk about failure, because it is not relevant to them. They talk about effort: because that is our only duty, the only thing within our control. The rest is not our responsibility. We cannot fail, because failure is not under our control. We may delay things or speed them up, but in spiritual terms we cannot fail, and so ‘failure’ becomes a redundant word. We should attach ourselves to the effort we have to make and avoid making judgments on our progress, for we do not understand the values that apply to spiritual matters.

Perhaps there is a gap between our ideals (where we want to get to) and the reality. In this case we can take heed of Henry David Thoreau, who wrote in his book Walden:

If you have built castles in the air your work need not be lost: that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them.

This is another way of saying that this is the time to put in some hard graft.

So by all means, let’s envision ourselves as higher, more perfect beings existing in a blissful environment, away from the mean features of this terrible world, and then act to realize the dream. The soul within is the perfect being, and we should always keep this dream alive: that we are part of the Master and of the Creator – an intimate part, not remote in any way. Now we should work to underpin that ideal.

For the Masters tell us that this ideal is the truth. We only have to work to experience it. Following the guidelines given so clearly by our Master, and accepting all the practical help that he gives us, we should keep that wonderful ideal in mind whilst we go about our duties, confident that we will indeed achieve our destination. For that is our birthright, and the means to regain it is our meditation, done with love and devotion – in the sense that Maharaj Charan Singh defines it, namely the practical sense.

All You Can Give

Clink, clink, clink, went the money into the collection box. The box was there so that worshippers could give back to God a proportion of the wages they had earned. Jesus, his apostles and other followers were sitting close to the temple and could see people depositing their coins into the box. A rich man strolled by and, making sure he was noticed, put ten silver coins into the box. A little while later, another wealthy man entered the temple and similarly, with some ceremony and pomposity, he deposited a hundred gold coins. Jesus did not remark upon their donations but continued talking to his followers, many of whom were impressed by the generosity of the rich men.

Dusk began to fall, and as Jesus and the small congregation started to gather their things to go home, a little old woman entered the temple and hobbled over to the collection box. From her bag, she took out a small, somewhat frayed purse, opened it and emptied its entire contents into her hand. Out dropped two pennies, which she deposited into the box without hesitation. Then, with the help of her walking stick, the little old lady made her way out. Calling his disciples to him, Jesus said, “Truly I tell you, this poor widow has put more into the treasury than all the others. They gave out of their wealth; but she, out of her poverty, put in everything – all she had to live on.”

I first came across this parable at school, when the headmaster recounted it one morning during assembly. I was profoundly affected by its message: that it is not the quantity of giving that is important but the love and selflessness with which we give.

Over the years, as I reflected on the parable from time to time, other meanings became evident, such as the old woman’s faith in God. She was able to give away all her money because she trusted in God and so had confidence that, like the birds in the sky, she too would not go hungry. Our Master also reminds us of this. Certainly, he does not encourage us to give away all our worldly wealth, but he does highlight the futility of being anxious about our economic circumstances. After all, these have already been determined by our karma. Moreover, indulging in worry will only undermine our spiritual practice.

Give quietly

The parable also draws attention to the old woman’s humility. Whereas the rich men did their best to ensure that people noticed their large donations, the little old lady made hers as discreetly as possible. Again, our Master also encourages this. Most of us are familiar with the aphorism Maharaj Charan Singh often quoted from the Bible, “do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing”, when donating to charity or as seva.

Until recently, I had always interpreted the parable in terms of its implications for monetary giving, oblivious of any other meaning. Then, one morning, as I struggled to sit still in meditation, the image of the old lady flashed into my mind. I was having ‘one of those sessions’, you know, when nothing seems to be going right and one becomes increasingly agitated. As I despaired at my failings, I thought about the old woman in the parable, how she had given everything she had and how much Jesus had valued her offering, which though small in a monetary sense was priceless in its generosity and the love with which it was made.

Maybe the same is true of our meditation. We ourselves may disregard those really difficult sessions, where we struggle to concentrate for a single round of simran or even to remain awake, as being worthless or pointless. But, if we have tried as hard as we can, have given everything that we have to give, it is highly possible that these moments are the ones our Master values the most.

The same might even be said of how much time we are able to give. We made a commitment to practise meditation for two and a half hours each day and should do our best to keep to this. However, our karmas may at times place us in situations where this becomes extremely difficult. Alternatively, we could be experiencing some form of mental anguish; maybe even losing interest in the path itself, so that sitting for even half an hour feels virtually impossible. Going back to the parable of the old woman, if in challenging conditions we meditate as best we can for however long we feel we can, is it not probable that our Master will recognize our efforts? As Maharaj Sawan Singh used to say, the inner Master is aware of all our difficulties and the circumstances in which he has placed us.

Let go of perfection

The present Master consistently reminds us that at our level, we tend to live by concepts. Like me, you’ve probably got a vision or an idea of the ‘perfect’ meditation session. It perhaps entails sitting cross-legged, spine straight, not moving one iota throughout the prescribed period of concentrated simran. The words of simran would be repeated naturally and easily, with the mind fully co-operative, concentrating hard with very little effort on our part.

This is an ideal that we’re trying to reach but that is all it is – an ideal based on our own individual concept of perfect meditation. So it’s silly to get upset if our practice falls short of our concept of the perfect meditation session.

If we think about this even more, by becoming upset with our efforts, aren’t we actually highlighting the strength of our ego? Many of us are in that ‘in-between’ stage, intellectually acknowledging that it will be the Master’s grace rather than our efforts that will carry us to Sach Khand, yet so far we have not evolved enough spiritually to surrender to him absolutely. This is the process that we are undergoing right now. When we reach the state of absolute surrender, we will acknowledge that we played no part in this at all. As Maharaj Charan Singh says in Die to Live:

You can say, “I am doing the meditation,” provided you are doing it. But when you really do it, then you won’t say, “I am doing it.” ‘I’ only comes in when we don’t do it. When we truly meditate, then ‘I’ just disappears. Then we realize his grace.”

Similarly, in Jap Ji we read that the absolute concentration we are seeking “is not dependent upon practice”, but that it is “through the Guru’s grace, [that] one’s mind is easily fixed in divine contemplation”. In other words, if we continue with our efforts, eventually the Master will shower his grace on us and it will be he, not we, who makes our minds absolutely still and engenders the state of effortless, deep meditation necessary to enter the tenth door.

Finally, turning once more to the advice and encouragement given by Maharaj Charan Singh in Light on Saint Matthew, we should always remember this:

If we but do our duty faithfully and carry out the instructions that we received at the time of initiation we have nothing to worry about. The Master will do the rest.

A Jug of Water

In the Masnawi of Jalaluddin Rumi, Book 1, a story is related of a Bedouin and a jug of water. Living in poverty in the Arabian Desert, the man and his wife agreed that he should go as supplicant to the famed Caliph of Baghdad. The caliph, known for his wealth and munificence, might have good things to bestow so that their pitifully restricted lives could be turned around. But how should they ingratiate themselves? What rare gift could they take to please him?

Eventually they decided on the thing most precious to them in that drought-ridden land – a jug of water. The wife earnestly assured her husband that the caliph might have gold and jewels but he would not have water like that. So off he went with a jug of rain water carefully sealed within a felt bag, carrying it day and night until he reached the caliph’s court.

The story describes his gracious reception; the caliph was a true king in every sense, and his own perfect manners were reflected in those of his courtiers. When the courtiers saw the jug of what was in fact nothing but ditch-water, they smiled but nonetheless accepted it and took the Bedouin before the caliph.

Little did the poor man know that the mighty river Tigris flowed through Baghdad. He had brought his pitiful little jug to one who lived beside this source of endless sweet water. But, we are told:

When the caliph saw the gift and heard his story, he filled the jug with gold and added other presents … saying “Give into his hand this jug full of gold. When he returns home, take him to the Tigris. He has come hither by way of the desert and by travelling on land; it will be nearer for him to return by water.” When he [the Arab] embarked in the boat and beheld the Tigris, he was prostrating himself in shame, saying “Oh wonderful is the kindness of that bounteous king and ’tis even more wonderful that he took that water.”

The story is a metaphor for the grace and compassion of those spiritual kings, the Masters. Maharaj Sawan Singh writes in Philosophy of the Masters, Vol. V:

Bees rush to flowers for their fragrance and honey; similarly, the seekers go to the perfect Master to partake of his wealth of spirituality and righteousness. No one returns empty-handed from the bountiful Master.

We are like the ignorant man and his wife – but our poverty is spiritual. In our spiritually arid world, we toil to collect a little devotion to present to the Master. How excellent our gift appears to us, but how little we understand of true spirituality. Nonetheless, with immense generosity, the Master accepts our poor offering and rewards us by giving us the wherewithal to turn our lives around. Maharaj Sawan Singh writes that “when anyone visits [the Master] he can see the visitor’s inner condition as if that person were encased in transparent glass.” Yet he never humiliates us by exposing our deficiencies and, in spite of his greatness, treats us with the tenderness of a mother.

Maharaj Sawan Singh continues:

When a disciple is reborn, so to say, in the family of the Master, he is ignorant of spiritual matters. His thoughts and cares are always entangled in low desires. But the Master stills the mind and senses of the disciple and purifies him.… Whenever the disciple encounters difficulties, he comes to his help.

Facing Death Calmly: Drawing Inspiration from Socrates

The ancient Greek philosopher Socrates held a spiritual view of life that resounds strongly with the teachings of saints and masters down the ages. His wisdom has been passed down in the form of conversations he had with his disciples, which were written down (perhaps many years later) by one among them, Plato. One such dialogue, the Phaedo, occurred on the day that Socrates died.

Socrates had been condemned to death by the authorities for corrupting the youth of Athens and causing them to disbelieve in the gods. From the point of view of many Athenians, having just lost a disastrous war, Socrates’ behaviour was tantamount to treason; he had displeased the gods and so lost the city their protection. Socrates vehemently defended himself against the charge but was convicted and condemned to die by drinking hemlock.

The following extracts are from the discussion with his friends and disciples in his prison cell, hours before his death. The most intensely spiritual of all his dialogues, it naturally focuses on the meaning of death and immortality. Phaedo, who was among those present in the cell, tells us that Socrates remained a model of calm throughout:

He struck me as happy, in both his manner and his words, so fearlessly and nobly did he meet his end.

After his chains are removed Socrates sits up on his bed and begins to massage his leg, remarking on the close connection between pleasure and pain: even now he experiences the pleasure of the removal of the chains after all the pain they had caused him. He is eager for discussion even though the warder has warned him that overheating himself with discussion will mean he will need a bigger draught of hemlock. Socrates talks with friends and disciples, but the text becomes more a monologue than a dialogue, with his friends only occasionally saying a few words in agreement (shown in brackets).

Socrates reflects on the nature of death

“Is death nothing more or less than this, the body being all by itself, separated from the soul, and the soul being all by itself, separated from the body? Surely death can’t be anything other than this, can it?

“It will be when we die – so the argument goes – and not while we are alive, that we shall attain what we desire and claim to be in love with – wisdom. After all, if it is impossible to gain pure knowledge of anything with the body, then we are left with two alternatives: either it is impossible to acquire knowledge anywhere, or it is possible only for the dead. Then, and only then, will the soul be by itself, apart from the body. And while we are alive we shall be closest to knowledge, it seems, if as far as possible we refuse to associate with the body or have anything to do with it beyond what is absolutely unavoidable. We must not infect ourselves with the body’s nature, but keep ourselves in a state of purity from it, until God himself sets us free. That is the way we can be pure and freed from the body’s foolishness.…

“And purification, as we saw some time ago in our discussion, consists in separating the soul as much as possible from the body and growing accustomed to withdrawing from all contact with the body and concentrating itself by itself; and to live on its own, as far as it can, both in this life and the next, freed from the shackles of the body. Does not that follow?”

(“Yes, it does.”)

“And the desire to free the soul is found chiefly, or rather only, in the true philosopher. Isn’t the practice of philosophy just this, the release and separation of soul from body?”

(“It seems so.”)

“So, as I said in the beginning, wouldn’t it be absurd for a man to be preparing himself in his lifetime to live in a state as close as possible to death, but then to become distressed when death came to him?”

(“It would be absurd.”)

“Then it is the case that true lovers of wisdom (philosophers) practise dying and to them of all men death is least terrifying.”

Socrates considers the soul

“Well then, did we also say a little while back that when the soul makes use of the body for any inquiry, whether through sight or hearing or any other sense – after all examining something using the body means examining it using the senses – it is dragged by the body into the realm of change? That it becomes erratic, confused and dizzy, as if it had drunk too much, through contact with things of a similar nature?”

(“We certainly did.”)

“When it looks at things by itself, on the other hand, the soul departs from here to what is pure, everlasting, immortal and unchanging; and being of a similar nature, when it is once independent and free from interference, then its wanderings are over, and it remains in that realm of the absolute, constant and unchanging because it is in contact with things constant and unchanging. Isn’t wisdom the name given to this state of the soul?

“If at its release the soul is pure and carries with it no contamination of the body, because it has never willingly associated with it in life, but has shunned it and kept itself separate as its regular practice – in other words if it has pursued philosophy in the right way and really practised how to face death easily, then this is what practising death means, isn’t it?”

(“Definitely.”)

“A soul in this condition departs to a place which is like itself, invisible, divine, immortal and wise; where on arrival happiness awaits it and release from its wandering and folly, its fears and wild desires and other human evils; and where, as those who have been initiated into the Great Mysteries say, it really spends the rest of time with the gods.”

The true philosopher enjoys true freedom

“But to join the company of the gods is not permitted to the man who has not practised philosophy and departed this life in a state of perfect purity. It is permitted only to the lover of wisdom.

“That is why true philosophers abstain from all bodily desires. They stand firm and do not give into them.… Every seeker after wisdom knows that up to the time when philosophy takes it over, his soul is a helpless prisoner, chained hand and foot to the body, compelled to view reality not directly but through prison bars, and wallowing in complete ignorance. And philosophy can see that the imprisonment is ingeniously brought about by the prisoner’s own desires, which make him the chief accessory to his own imprisonment.

Well, philosophy takes over the soul in this condition and by gentle persuasion tries to set it free. She points out that enquiry by means of the eyes and ears and all the other senses is entirely deceptive, and she urges the soul to refrain from using them unless it is necessary, and encourages it to collect and concentrate itself by itself, trusting nothing but its own contemplation on itself and by itself; to attribute no truth to anything which it views indirectly as being subject to change because such objects are visible and of the senses, but what the soul itself sees is invisible and seen directly. The soul of the true philosopher feels that it must not reject this opportunity for release, and so abstains as far as possible from pleasures and griefs and desires because it realizes that the result of giving way to pleasure or fear or desire is not the trivial misfortune of becoming ill or wasting money through self-indulgence, but it is the greatest and worse of disasters.

“Every pleasure or pain has a sort of rivet with which it fastens the soul to the body and pins it down and makes it of the body, accepting as true whatever the body does. The result of agreeing with the body and finding pleasure in the same things is, I imagine, that it cannot help becoming like it in character and its way of life so that it can never reach the other world in a pure state, but is always saturated with the body when it sets out and so falls back into another body, where it takes root and grows. And so it is excluded from all communion with the pure, the divine and absolute.”

(“Yes, that is perfectly true.”)

“That is the reason why true lovers of knowledge are self-controlled and brave. It is not for the reasons that most people give.”

(“No, certainly not.”)

“No, indeed. The philosopher’s soul will take the view I have described. It will not expect first to be set free by philosophy and then allow pleasure and pain to reduce it once more to bondage, so taking upon itself an endless task…. No, this soul secures a retreat from its desires by following meditation and staying always in its effects, and by contemplating the true and divine and drawing inspiration from it; because such a soul believes that this is how it should live for as long as it does live, and that when it dies it will come to a place similar to its own nature, and there it is rid for ever of human evils.”

Socrates drinks the hemlock

“But at least one may pray to the gods that my removal from this world to the next will be a happy one; that is my own prayer; so may it be.”

With these words he pressed the cup to his lips and drank it off with good humour. Up until this time most of us had been fairly successful in keeping back our tears; but when we saw that he was drinking, that he had actually drunk it, we could do so no longer; in spite of myself the tears came pouring out, so that I covered my face and wept broken-heartedly – not for him, but for my own calamity in losing such a friend. Crito had given up even before me, and had gone out when he could not restrain his tears. But Apollodorus, who had never stopped crying even before, now broke out into such a storm of passionate weeping that he made everyone in the room break down, except Socrates himself, who said: “Really, my friends, what a way to behave! Why, that was my main reason for sending away the women, to prevent this sort of disturbance, because I am told that one should make one’s end in a calm frame of mind. Calm yourselves and try to be brave.”

This made us feel ashamed, and we controlled our tears. Socrates walked about, and presently, saying that his legs were heavy, lay down.… The coldness was spreading about as far as his waist when Socrates uncovered his face – for he had covered it up – and said (they were his last words): “Crito, we owe a cock to Asclepius. See to it and don’t forget.”

“No, it shall be done,” said Crito. “Are you sure there is nothing else?” Socrates made no reply.

Such was the end of our companion, who was, we may fairly say, of all those whom we knew in our time, the bravest and also the wisest and most just man.

Book Review

The Other Buddhism: Amida Comes West

By Caroline Brazier

Publisher: Winchester, UK: O Books, 2007.

ISBN: 978-1-84694-052-1

A major theme in Caroline Brazier’s The Other Buddhism: Amida Comes West is that we ordinary mortals are incapable of successfully practising spirituality on our own and need the help of some enlightened being to achieve salvation. Pureland Buddhism’s answer to that need is nembutsu, the practice of calling on the name of the Buddha Amida, “the immeasurable expression of Buddha in the universe”. Brazier presents an in-depth exploration of the implications of a spirituality that relies not on the efforts of one’s self – which, though appreciated, are ineffective – but relies instead on what she broadly terms ‘the Other’.

The Amida school of Pureland Buddhism is the predominant form of Buddhism in Japan, although Zen Buddhism, also rooted in Japan, is better known in the West. Pureland and Zen teachings are often presented as mutually exclusive, but this is more an intellectual assessment rather than the reality on the ground. In fact Amidism is often practised in the same temples and by the same practitioners as Zen. Caroline Brazier, an engaged Buddhist and an active practitioner of Pureland Buddhism, writes in the preface:

This book offers a simple exploration of Pureland Buddhism. It is an attempt to convey something of the flavour of this rich tradition and to offer a way to practice in the Western context. The central message is one of hope that comes from an approach to faith which is both open and joyous. The core values of gratitude, humility and wonder, community and love speak to our condition.

Brazier begins with a discussion of the Buddha’s teachings on the Four Noble Truths. This fundamental teaching, accepted by all schools of Buddhism, “shows how we react to afflictions (dukkha). When we are faced with loss or affliction, feelings arise in us (samudaya) which are uncomfortable. One immediate reaction is to seek ways in which we can distract ourselves from this feeling. We develop craving for distraction (trishna).” Our sense of self, while illusory, is maintained and solidified through continual occupation with distractions.

According to Buddhist psychology, the sense of self can be seen as a way in which we attempt to control an apparently uncontrollable universe. In building our identities, we attempt to hold onto a feeling of permanence and continuity in the face of constant flux.… If building an unassailable sense of self is our aim, its constant erosion by reality creates distress and fear and this in turn drives us to want to create a more secure and rigid sense of self.

The Buddha’s teachings suggest that people “can unhook themselves from the object of their craving”. As the author expresses it, in the Four Noble Truths Buddha teaches that:

If we are able to interrupt the cravings that are taking over our lives, then the energy embedded in the feeling responses that arise in us can be harnessed (nirodha) for the spiritual path (marga). Our grief can become the fuel for our spiritual life. Once harnessed, we will naturally live in a way that is in tune with that way of being.

Brazier comments that this teaching “sounds good in theory, but the difficulty arises when we ask ourselves how we should go about putting it into practice”. We may try to break out of our deeply embedded mental patterns, but, she says,

The undercurrents of unconscious processes, of unrecognized manifestations of greed, hate and delusion, the three poisons that lie at the core of all mental afflictions according to Buddhist theory, pull us back into old habits. Our minds have unfathomable depths. We are as leaves on the surface of a pond, drifting with the currents that the wind whips up.

So far this dilemma is common to all forms of Buddhism. As Brazier explains it, Pureland Buddhism’s response to this dilemma is, in a nutshell, that “we are not of the nature to save ourselves through our own efforts”. Human nature is called bombu, a Japanese word with a derogatory meaning of ‘foolish’ or a ‘common person’. For many practitioners, the recognition of their own bombu nature does not come until after making great efforts to reach perfection and, on confronting complete failure, plunging into despair. Then, Brazier says, “We come face to face with our imperfect nature and drop our façade of competence. The despair that accompanies such an experience is the springboard for a more solid approach to life.”

According to Brazier, “The connection with what is not-self is the central message of the Buddha’s teaching.” In Pureland Buddhism, the Buddha Amida is ‘other’, a reality beyond the confines of the illusory self. But, the author clarifies, everything that is not-self is also ‘other’. In our unenlightened state, we believe that only our self is real, and do not even see other people or things as real. “We use each other as props to our psychological structures. In doing so, we do not respect others or recognize them as having existence in their own right. We incorporate them into our own agendas and viewpoints. Doing this we subtly undermine the integrity of life.”

Pureland Buddhism points us towards a deep appreciation for what is other… It sees the person as caught in a morass of deluded thoughts and perceptions. It sees how we are rescued time and again by the others in our lives. We are held and supported by our environment. We are cared for by other people. We live through grace.

But as we begin to awaken to our helplessness, our bombu nature, we begin to see that:

Despite all our limitations and failures, we are still wonderfully looked after. Despite our incompetence and lack of imagination, bigger processes of life go on. Beyond the messy realities of our individual lives, the great stories of history unfold. Despite all the problems of humanity, the sun still rises, and often the world is a beautiful place. All this we take for granted. Yet on it we ground our lives.

The author explains how “we are in a state of great dependency. We need food in order to stay alive, but the crops do not need us. We need sunlight, but the sun does not need us. We need air to breathe, but the atmosphere is not dependent on human activity to maintain its oxygen levels.”

With the dawning of such realizations, our awareness of non-self begins to develop.

Brazier points out that “gratitude is a fundamental aspect of Pureland Buddhism”. Opening up to gratitude is not easy. It “involves facing our pride and letting go of some of the defensive structures which we have created in order to protect us from knowing our vulnerability and dependence.” Through gratitude, even for ordinary gifts in our everyday lives, we begin to “allow ourselves to see the hidden workings of the universe, the compassion that surrounds and maintains our lives. This is both moving and difficult. There can be many tears.”

At a spiritual level, this willingness to allow other-power to take over from self-power is a moment of renunciation. It is the act of taking refuge.… Recognizing our limits brings us to the point where we no longer struggle. We are willing to let go and to allow ourselves to be rescued. It is often only when all else has failed that we go for refuge.

Thus, we develop “an attitude of appreciation that goes beyond the worldly to the transcendent”. As Brazier writes, “Although we may take refuge in other people, in physical objects and places, ultimately it is our relationship to the transcendent which sustains us.”

The author ends her book confessing the darkness of human nature and affirming the light: “For we are bombu. Our bombu nature has brought us to the brink. Not recognizing our limitations, we have forgotten how to sing in gratitude. We have lost our connection to the great, the wonderful and the immeasurable. Let us remember before it is too late. So in the dark times, will we dance in the light.”

Book reviews express the opinions of the reviewers and not of the publisher.