Download | Print | Archives

March 2018

The Eternal Quest

Your Humble Devotee

The First Principle of Faith

Building Faith

Ready for Grace

When Fruit Is Ripe

A Lasting Effect

The Value of Every Breath

Smoke and Mirrors

Presence

Detachment and Parenthood

Truth in a Nutshell

Feeling Funny

Are You Worried?

The Patient Saint

The Invitation

What about Demons?

Feeling Upset

Happy, Relaxed and Divine

Book Review

Start scrolling the issue:

The Eternal Quest

Mindfulness or remembrance of the Divine requires constant vigilance to keep the attention focused on the innermost essence of being, to retain awareness of our own essential being. Not to be continuously carried away on the current of thought and emotion, but to remain conscious and aware. This is the soul’s response to the divine call, and he is forever waiting for us to turn to him. Indeed, he is the one who prompts us from within, and makes us turn.

We already have everything we need, here and now, in the sacred present, the eternal now, within our own being. The One Being is always with us, never far. “Closer is he than breathing, and nearer than hands and feet.”

The divine beloved is our guide, drawing us ever on. Our effort is simply a response to his call. “If we take one step towards him, he takes a hundred steps toward us.” And he is the one who makes us take that one step. His grace is inestimable. His love is incalculable. We live in it, could not exist without it. If our attention is distracted and we turn our back on it, we may think he has gone away. But he is always present. There is nowhere else for him to go. He is helpless in his love for us, united by the bond of shared and indistinguishable being.

So, to find him is the eternal quest, the only journey worth travelling with all our heart and soul. To remain seekers until the journey’s end.

Never to give up, to remain positive, to let go of despondency and negativity, and become aware of the One.

One Being One

Your Humble Devotee

Lord, I stand before you in humble supplication:

why am I so disconsolate, my Lord,

when I am in your court, under your blessings?

There is no giver like you; you have carried

countless souls across the ocean of existence.

But this abandoned sinner is still awaiting her turn.Just as a moonbird pines for the moon,

the pearl shell for the swaanti raindrops

and the peacock for the dark cloud,

I am restless, O Lord, for a glimpse of you.You are the lamp, I am a moth.

In your flame

I have burnt my mind to ashes.

I have met the perfect adept in you, Radha Soami,

you have transformed this helpless insect, as does a bhringi.

You are the sandalwood tree, I am a snake,

taking shelter in you has soothed my mind.

You are the ocean, I am the wave,

from you I arose, in you I am finally merged.

You are the sun, I am a ray of light,

from you I emerged, to you I have returned.

You are the pearl, I am the string,

never am I really separate from you.

Sar Bachan

The First Principle of Faith

As societies in Western Europe have become more secular, faith in God or in some form of supreme intelligence is often viewed as irrational. Modern science contends that ‘truth’ is to be found in ‘facts’. However, only phenomena that can be observed, measured, and verified come to acquire such a status. The notion that anything exists beyond material or sensory experience is rejected. The natural sciences are thus preoccupied with uncovering the physical laws of the universe, describing, often in minute detail, their intricate patterns, complexity, and order.

How such laws have come into existence is a question considered to be inexplicable or best left to metaphysics. Nonetheless, it is data and knowledge accumulated by science that provides the best material evidence that the universe has not occurred randomly. The Anthropic Principle for instance, which sets out all the multitude of coincidences that render the cosmos suited to life, makes it difficult to draw any conclusion other than that it has been created by a supreme consciousness. Call it God or any other name. Not coincidentally, this is a universal truth expressed consistently in all mystical literature.

The passages reproduced at the end of this commentary are good examples of such truth: the first is a passage from the Bible, the second is the Mool Mantra, the opening stanza of the Sikh scriptures Adi Granth, and the third is a Hasidic poem inspired by Ecclesiastes, one of the books of the Bible.

Written at different times, in different places, and for different audiences, all three excerpts begin by explaining that God exists, with the first line of the Hasidic poem emphasizing that accepting his existence constitutes the first principle of faith. This is similar to the response Jesus makes in Saint Mark’s gospel in the Bible when asked which was the single most important commandment: “Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is one.” The opening line of the Mool Mantra also underlines the existence of one God, meaning that he is the single source from which the entire universe has sprung.

The excerpts explain that God brought himself into existence and, in doing so, went on to establish his creative power, a great dynamic current, called the Word, Name, or Hokhmah, the Hebrew term for wisdom. It is God’s creative power that created the universe and now sustains it and the life of all things in it. Using language that is more familiar to us, the author of Yoga and the Bible describes this Word in the following way:

All life and energy in the universe come from the divine Word. It is a power that is mightier than any known on earth, for it is the power behind all other powers. All other powers are finite, but this power is infinite. It is the one basic power in the universe. It shows itself in many apparently different forms of energy; but trace them back to their original source and they are all found to be fundamentally one – the dynamic power of God. It dwells hidden, but supremely active, at the back of all other energy.

God’s creative power is thus the very essence and life-force of all things, ourselves included, as the Bible makes clear in the opening passage of Saint John’s gospel: “In him was life; and the life was the light of men.” In other words, the power of God, which brought the universe into being, is the same energy that is our own real self. Although God dwells within us and is our very life, he remains invisible in much the same way as does, for example, the fragrance within a flower. Realizing him through the intellect is also impossible. Nonetheless, in an attempt to understand something of what God is, mystical literature seeks to identify his many attributes. The Qur’ān, for instance, ascribes ninety-nine qualities to Allah. Collectively known as ‘The Most Beautiful Names’, each one is intended to explicate an aspect of his essence. Likewise, the Mool Mantra describes God as unborn, self-existent, without fear, without enmity, and of timeless form. Each attribute conveys esoteric insights of such profundity that the entire Jap Ji is devoted to explaining what they mean.

Love is the essence

Depending on our mood, we may find reading about the various qualities of God to be inspiring, unimaginable, unfathomable, and perhaps frustrating. We may feel distant from him, since the nature of his supremacy is so utterly beyond our experience that relating to him proves difficult. There is, however, one quality emphasized by the mystics above all others to which we can relate – love. This is the essence of God, and since our essence is the same as his, our defining quality is also love. We experience this each time we are the agents or the recipients of kindness, compassion, generosity, gentleness, nurturing, and patience; when we are joyful for no other reason than simply being; when we feel calm, peaceful, and content. Love is the driving force behind all the acts of goodness taking place each moment throughout the world. As Maharaj Charan Singh said, without love, the world would cease to exist. In Spiritual Perspectives, Vol. III he also reminds us that, “He is the one who gives us his love … love is a gift given to us by him, and the more we love, the more it grows.”

The greatest expression of God’s love for us is that, despite his incomprehensibility, he makes it possible for us know him – as explained in the last line of the Mool Mantra – by following the instructions of a true Master. Influencing us with his love, it is the Master who teaches and helps us realize that within the depths of our being resides love, wisdom and peace – in short, the divine Word of God. If the many beautiful shabds are anything to go by, it is clear that seekers throughout the ages have been rendered helpless by the love and magnetism of the Masters. Our own personal experience testifies to this too. Yet the end point of spirituality is not the physical form of the Master. Our love for him, to paraphrase Maharaj Charan Singh, should foster love for the Divine. The following excerpts remind us of his existence.

In the beginning was the Word

and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.

The same was in the beginning with God.

All things were made by Him;

and without Him

was not anything made that was made.

In him was life; and the life was the light of men.

Bible, John 1:1-4

There is but one God;

true is his Name.

He is the Creator,

without fear, without enmity

and of timeless form.

Unborn and self-existent,

he is realized through the Guru’s grace.

Jap Ji

The first principle of faith is that God exists.

He was first, and he created all things, above and below –

His creations are without end.

All began with a single point – the point of Supernal Wisdom.…

Believe with complete faith that God fills and surrounds all worlds,

He is both within and beyond them all.

Rabbi Menahem Nahum of Chernobyl, “Hanhagot Yesharot,” in God in All Moments

Building Faith

The Oxford dictionary gives two definitions of faith. The first is to have “complete trust or confidence in someone or something”. Spiritually, trust is the basis upon which our faith evolves. Thus, we begin the mystical path by placing trust in the Master, envisaging that he will help us find the Truth. As Maharaj Jagat Singh states in The Science of the Soul, “unless we have faith in the method revealed by the Master, we cannot expect to make progress. Faith in the Master’s instructions is necessary for advancement on the path. If a student has no faith in his teacher, he will not learn.”

Whilst our faith is initially intellectual in nature, it is the driving force making us meditate. As Maharaj Charan Singh explains in Die to Live:

You must have faith in the path which you are following, that this is the path which goes back to our destination, and faith in the one who has put you on the path … and he’s always with you to guide you to the right destination. Unless you have that faith, you will never practise meditation. Faith doesn’t take you to the destination. Practice will take you to the destination, but faith will make you practise.

The second definition of faith given by the Oxford dictionary is holding “strong beliefs in the doctrines of a religion, based on spiritual conviction rather than proof”. The philosophy of the path of the Masters, however, is based on scientific inquiry and personal experience as the route to truth. The mystics expect us to nurture the gift of faith bestowed upon us. By using the spiritual tools we are given and searching for the proof personally, over time, our faith, which was once rooted in spiritual concepts, evolves, strengthens and becomes unshakable because of personal experience.

Ready for Grace

The quotations below are reproduced from Paul Brunton’s book, The Gift of Grace. Devoting his life to spiritual inquiry, the twentieth-century British theosophist concluded that an infinite power is the source of our existence and our constant guide. Grace and all its inherent properties – support, sustenance, goodness and light – is ceaseless and all-encompassing. It is not conferred to a ‘special’ person and denied to another. Receptivity, though, is our responsibility.

Feel even in the very heat of this world’s activity that your guardian angel is ever with you, that it is not farther away than your own innermost heart. Nurture this unshakeable faith, for it is true. Make it the basis of your conduct, try to ennoble and purify your character incessantly, and turn every failing into a stepping-stone for a further rise. The quest winds through ups and downs, so you must make despair a short-lived thing and hope an unkillable one. Success will not depend on your own personal endeavours alone, although they are indispensable; it is also a matter of grace and this you can get by unremitting prayer addressed to whatever higher power you believe in most, and by the compassion of your guide.

It is true that grace is given, but we ourselves help to make its blessing possible by the opening of self to receive it, the silencing of self to feel it, and the purifying of self to be fit for it.

Remember always that you are present within It and It is ever present within you. So the source of grace is in you too. Silence the ego, be still, and glimpse the fact that grace is the response to devotion that goes deep enough to approach the stillness, is sincere enough to put ego aside. Help is no further off than your own heart.

The grace works from your centre outward, transforming you from within, and therefore its earliest operation is unknown to your everyday mind.

Grace flows in wavelengths from the mind of an illuminated man to sensitive human receivers as if he were a transmitting station. It is by their feeling of affinity with him and faith in him that they are able to tune in to this grace.

It will not be until a late stage that you will wake up to the realization that the real giver of grace, the real helper along this path, the real master is not the incarnated master outside but the Overself inside your own heart. What the living master does for you is only to arouse your sleeping intuition and awaken your latent aspiration, to give you the initial impetus and starting guidance on the new quest, to point out the obstructions to advancement in your individual character and to help you deal with them.

Grace flows from such a man [a mystic] as light flows from the sun; he does not have to give it.

When Fruit Is Ripe

A letter from Baba Jaimal Singh Ji to his disciple Sawan Singh:

Hazur Din Dayal is always with you in the form of Shabd Dhun. He is doing what he wants to do. You should not argue or put in your point of view. You should remain within the instructions of the Satguru and also attend to worldly work. When the fruit is ripe, it drops of itself from the tree, without causing any harm or pain either to itself or to the tree.… But if the fruit is plucked while it is still immature, it shrinks and dies. And the branch of the tree or the stem of the creeper from which it is plucked by force, begins to water, and the fruit cannot be used.

If you come across a perfect Master while you are in the human body, then you have achieved everything. This is the fruit. To obey the words of the Master is like the ripening of the fruit. To attend to bhajan and simran every day to the best of one’s capacity is like watering the fruit. To become one with or to be merged in the Shabd Dhun is the falling of the fruit after maturity. Then nobody suffers.…

The world, the family, parents, wife, wealth, property, worldly glory, all these constitute the tree. The love and attachment of the mind and the surat is the fruit attached to this tree. When the mind will obey the commands of the Satguru and not transgress his words (bachan), then it will love the Shabd Dhun, [and] the surat will take on the form of the Shabd Dhun.… Then the ripened fruit will fall of itself.… Listen every day to the Shabd Dhun as long as you can. One day you will reach Sach Khand.

Spiritual Letters

A Lasting Effect

At our Satsang Centre there is an area of hardened ground that was laid down some years ago. It’s where sevadars and sangat collect. Here and there on this large expanse of concrete, if you look hard you can find a few small, delicate leaf prints. Whilst the concrete was still setting, some of the leaves must have drifted down from the trees above. So, while the leaves themselves disappeared long ago, their imprint has remained, a record of fragile beauty, of a moment in time. They make me smile.

Our actions in life, so quickly over and gone, leave a print just like the oak leaves, though less visible. We may think of this in a fearful way – our “karmic record”, all those mistakes we won’t be able to hide from on the day of judgement. But equally, isn’t it a happy thought that what we do matters? That the moment passes away but that what we do in it will remain, just as surely as the pattern in the concrete?

If we do things that are right and good, with an honest heart – kind words, a smile, looking out for someone in need – the benefit to others remains and becomes part of a general good that lives on long after us. Of course, the important thing, from our point of view, is to do this without expectation of reward; to love for love’s sake, for no other reason than that. In the gospel of Saint Matthew in the Bible, we read that Jesus advised:

When thou doest thine alms, do not sound a trumpet before thee, as the hypocrites do in the synagogues and in the streets, that they may have glory of men.… But when thou doest alms, let not thy left hand know what thy right hand doeth.

If the one hand doesn’t know what the other is doing, it means that we are not conscious of doing anything praiseworthy, let alone letting others know. We have to set our compass towards the positive and then just go for it. To avoid falling into the traps of egotism, once we know where we’re heading (towards our Master), a lack of self-awareness is the best protection. Where there was once self-interest, there can be concern for others.

There is a story of a child on a beach: he found thousands upon thousands of tiny sea creatures washed up on the tide line after a storm. He began to scoop up the dying creatures and hurl them back into the retreating sea. After he had been doing this for some time, making seemingly no impact at all, an adult came up and said, “You’re wasting your time. It’s not making any difference.” The boy just gave a look and picked up and threw another handful far out to sea. “It makes a difference to them,” he replied.

We should learn from the child and never be disheartened by the thought that we’re contributing so little. This is a mistake that we sometimes make in seva. We look for a ‘product’ at the end, something tangible to point at and say “I did it!” But that defeats the purpose of seva, which was never about ‘products’ or ‘us’ in the first place. In seva it’s more about just putting your hand up (metaphorically speaking) to say “Count me in!” It’s about giving our support, in any way we can, to something special and meaningful. Just as the child latched on in an unspoken way to the needs of the tiny creatures, so we latch on to the need for spiritual values to enhance all we do on the human plane. We may only carry a teaspoonful of earth to build the castle but it’s the fact that we do it at all that’s important.

One of the central characters in a nineteenth century English novel, Middlemarch,is a young woman who longs to do something great and meaningful. After she becomes resigned to a more ordinary and unremarkable life, the novelist concludes that although this was less than she had intended, her good and loving acts could be seen as “diffusive” – they made everything that little bit better. She writes, “The growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the [people] who lived faithfully a hidden life.” Maharaj Charan Singh says in Spiritual Perspectives, Vol. III:

We have a wrong concept if we think that our heart should not be soft. It should be very, very soft.… We should have a kind and loving nature and try to be helpful to others, good and kind, loving to everybody. Actually, when you love everybody, you don’t love the individuals, you love the Lord who is in everybody. When you are filled with love and devotion for the Father, you also develop a loving attitude towards his creation, even birds and animals.

Our lifetime is invaluable. We must always be careful to use it in the best direction. Any part of our time not used in spiritual practice is lost. Therefore you should always try to save your time for meditation, because to incline our mind and spirit towards the things other than the Holy Sound is to lose our fortune.

Maharaj Sawan Singh, Dawn of Light

The Value of Every Breath

I declare to the loud beat of drum:

With every breath that passes

In forgetting the Name of the Lord

You are losing the chance to conquer the three worlds –

Your chance to reach the spiritual heights.What guarantee have you of life?

Your body may be destroyed in a single moment.

With every breath, therefore,

Remember the Name of the Lord –

Forget all other callings.…Remember, only those breaths truly bear fruit

That you spend in remembrance of the Name.

All other breaths you spend scheming and planning –

All are totally useless.Kabir, as long as there is life

Fearlessly continue repeating the Lord’s Name.

When the oil of life is exhausted

And the wick of the lamp is extinguished,

There will then be quite enough time

To sleep both day and night.

Kabir, The Great Mystic

Smoke and Mirrors

“That which I should have done, I did not do.” This is the intriguing title of a sculpture produced by the American artist Cy Twombly who died in 2011. The title conjures an image of time, energy and focus being diverted from the pursuit of some other more precious activity. As seekers embarking on a spiritual journey, this raises an important question: Are we practising meditation consistently or do we let other demands take priority? Two recent RSSB publications, Concepts and Illusions and A Wake-up Call, point out that we are fairly adept at what organization theorists term ‘decoupling’ – creating the illusion of adopting approved habits and practices whilst privately following a different course. In terms of Sant Mat this relates to following the outward life of a spiritual seeker whilst actually prioritizing worldly interests. So, judging our behaviour purely on our actions, perhaps the more accurate question is: are we living Sant Mat or faking it?

From maya to self-deception

Reflecting on the extent to which the path of the Masters has become a way of life, many of us would tell ourselves that, whilst there is room for improvement, overall we are living Sant Mat and living for Sant Mat. We would contend that the philosophy of the mystics not only provides the framework by which we make sense of the world, but is the driving force underpinning our motives, attitudes, behaviour, routines and, ultimately, our sense of self. In fact, we would say that, since Sant Mat now pervades our entire being, it is impossible for us to live a ‘non-Sant Mat’ way of life even were we tempted to do so. We would point out that by being vegetarian, attending satsang, performing seva, and, above all, devoting time to meditation, we are seeking to fulfil our most important duty as disciples.

Yet, to what extent is our meditation genuine? Why are we doing it? Are we motivated by a deep desire to reconnect with the Shabd and, thus, purposefully direct our daily activities to fit around this? Or, has meditation become a ritual, a ‘tick-box’ exercise in which we conform superficially to the expectations of what it is to be a disciple whilst being preoccupied with the desires, demands and expectations of life on the material plane?

Organizations engage in decoupling practices to create the impression of compliance with external stakeholders’ expectations (e.g. incorporating green business practices) without actually changing their operations because this would detract from what they view to be their primary purpose (making a profit). Here, the target of decoupling is external i.e. consumers, pressure groups, regulators and media. As spiritual seekers, the target of decoupling is primarily our own self.

Cleaning up our act

We spent aeons deluded by maya until the mystics showed us the truth. However, our new found enlightenment does not preclude self-deception. In Sar Bachan Poetry, Soami Ji Maharaj concludes that the “one thing” he has learnt about us is that, “you are remarkably dishonest with yourself.” The gap between our stated desire for spirituality and our practice is reiterated by Maharaj Jagat Singh in The Science of the Soul when he states that, with our mind “still steeped in cravings for the world and its objects”, our desire for Nam is a sham.

Not practising meditation is problematic, but practising meditation in any of the ways described below is also problematic because we risk deluding ourselves that we are making best use of the invaluable opportunity of human life and that, with the Master’s grace, we will be returning home. In various places in The Dawn of Light, Maharaj Sawan Singh makes clear that until we are completely cleansed, the inner Master will not make himself known, and without this guidance we cannot reach Sach Khand. The present Master has reminded us that many of us have yet to begin the cleansing process in meditation. This suggests many of us are still in the nursery, learning the ABC of meditation with the inner journey yet to begin. Thus, being honest with ourselves as to whether Sant Mat has become a way of life is a matter of urgency.

How sincere are we?

Practising meditation regularly and punctually is the foundation step in disciplining the mind and building a relationship with the Lord. Yes, some of us have heavy family and work responsibilities and it does happen that meditation becomes sporadic. Again, shift work patterns can make it necessary to swap the time of our sitting so that punctuality as such is difficult. As Maharaj Charan Singh used to remind us, loving attention to simran in the day is a way of remaining true to the way of life. But, that said, if we don’t keep watch on ourselves and do our best to take every opportunity to establish a conscientious routine of meditation, it calls into question our level of sincerity. In contemporary society, it is impossible to get through life without keeping appointments. Why then do we not extend the same courtesy to the Master, especially since we are asked to do so? If we were to get anxious about keeping the Master waiting, as we do when late for an exam, a business meeting, or picking up children from day-care, this would indicate that meditation is becoming of paramount importance to us.

How much time we devote to meditation is a further indicator of our commitment. If we consistently devote less time than the minimum required, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that our desire to reconnect with the Shabd is superficial. Each time we sacrifice a minute of meditation, we are signalling that the outward world takes precedence over cultivating our relationship with the Lord.

Falling asleep during meditation because we are tired is a further barometer signalling that we may be giving so much of ourselves to the fulfilment of personal desires and obligations that there is hardly anything left for meditation. Yet, if we believed wholeheartedly that this was the most important activity of the day, we would reserve our greatest energy and the very best of ourselves. We would approach each session much like, for example, a student undertaking an exam: rested, prepared, alert, and completely focused.

Our main focus

How we feel about meditation is yet another indicator as to whether Sant Mat has become a way of life. In The Dawn of Light, Maharaj Sawan Singh states that right up to the last breath, “determination and faith should be so strong that even if nothing comes out of it … there is no wavering.” Given how often we tell the present Master that meditation is difficult or beyond our capabilities, our defeatist attitude signals that liberating our soul has yet to become our primary purpose in life. By far the most common attribute of individuals who reach the very pinnacle of their profession – be this in sport, science, medicine, art, music – is resolute determination; a single-minded persistence to reach their goal despite experiencing failure and adversity along the way. The dedication and tenacity with which they approach their objective is inspiring and instructive.

Unless we can honestly say that we are putting in our best effort to practise meditation consistently, we should be careful of falling into the trap of self-deception – thinking that we are living Sant Mat and living for Sant Mat when actually we are living for something else. There is a tendency for us to practise meditation just enough to hope that, with the Master’s grace, this will be sufficient to reconnect with the Shabd. But the inner Master is not as easily duped by our motivations and desires as we are. Despite our heartfelt desire not to return to the material plane, this is precisely the future that awaits us unless we make Sant Mat the central focus of our life.

Anything that helps us in our concentration and inward progress is worth doing; all else is off the mark. The world may be deceived, self may be deceived, but he that sits within cannot be deceived. He will open the door only when he has tested our fitness and found us worthy.

Maharaj Sawan Singh, The Dawn of Light

There is no doubt that our own endeavours do play a part in what we receive, but without the Lord’s merciful grace, even our best efforts cannot result in success.

We see our own effort, but we do not see the Lord’s grace. We have created neither earth, nor fire, nor have we had any hand in the creation of water, sky or sun. We mine iron, coal and gold from the earth, but we do not create them ourselves. We excavate diamonds from the mine but we do not make them. We extract oil and gas from under the ground, but we do not put it there. Everything is dependent on the gifts created by the Lord. Without his love and benevolence, we would have nothing.

Jap Ji: A Perspective

Presence

“Where shall I look for Enlightenment?”

“Here.”

“When will it happen?”

“It is happening right now.”

“Then why don’t I experience it?”

“Because you do not look.”“What should I look for?”

“Nothing. Just look.”

“At what?”

“Anything your eyes alight upon.”

“Must I look in a special kind of way?”

“No. The ordinary way will do.”“But don’t I always look the ordinary way?”

“No.”

“Why ever not?”

“Because to look you must be here. You’re mostly somewhere else.”

Anthony de Mello, One Minute Wisdom

Detachment and Parenthood

All mystics impress upon spiritual seekers the importance of trying to become detached from the world because union with the Lord occurs only when we are free from the ties binding us to the material world. Detachment, the process of disconnecting the mind from the external world, requires us to live in the world but not to be of the world. Maharaj Charan Singh gives the following analogy in Quest for Light to explain what this means:

A follower of Sant Mat should enjoy life just as a bee sitting on the rim enjoys the honey in the cup. It enjoys the sweetness of the honey and flies away with clean wings. But if that very bee were to sit in the middle of the cup of honey, its wings would be soiled and it would drown, thus giving up its life.

The Master explains that leading a spiritual life does not mean closing ourselves off to all that is enjoyable but neither should we become so engrossed in pleasures, activities and relationships that we neglect cultivating a relationship with the Lord. Whilst it is hard to disagree with the logic of this advice, it is not always easy to put into practice – especially as a parent. Of all our many relationships, the parent-child bond is the strongest, raising the question of how exactly we are to remain detached whilst parenting – a life-long commitment that is second only to our commitment as disciples. This article offers one perspective on managing this tension.

Attachment to material possessions

Although our tastes, desires and lifestyles differ, generally, our attachments fall into three categories, each of which forms a barrier between ourselves and the Lord. First are material possessions and symbols of wealth and status. The amount of time and energy we devote to work often exceeds that which we need to meet our needs comfortably. Sometimes we justify this by saying that we want to pass material benefits on to our children. Yet the best legacy we can leave them is the example of good human values and love for the Lord.

Attachment to family and friends

Attachments to family and friends are yet more powerful because the strength of these bonds directly hinders our progress on the spiritual path. Indeed, in Saint Matthew’s gospel in the Bible Jesus states that “a man’s enemies will be the members of his own household” because they command so much of our attention. We have a habit of going beyond the duties required of the familial roles to which we are assigned. Our attachment blinds us to their transitory nature and the realization that all relationships, no matter how deep they appear, are nothing more than the settlement of karmic accounts. As Maharaj Charan Singh explained, “We are like birds that take shelter in a tree in the evening, but with the first light of dawn, each flies off on its own way.” In our illusion, we fail to recognize that our real relationship is with the Lord. This began before time and it is the revival of this connection that should preoccupy our thoughts and efforts.

Attachment to the self

Our third attachment, to the self and the ego, is by far the strongest of all and accordingly constitutes the biggest barrier. Our sense of ‘me’ and ‘I-ness’ – the belief that one has an independent self – is the cause of our entrapment in the cycle of birth and death. In fact, as explained in Buddhism: Path to Nirvana, the concept of the individual self is so detrimental to spiritual practice that in answer to the question of what should be eradicated, the Buddha always replied, “The conceit of I.” It is this conceit of “I-ness” that makes us think in terms of “my husband”, “my wife”, “my daughter”, “my son”. And the sense of ownership, besides being mistaken, can create conflict as children grow up and seek an independent life. Loving should not involve possession.

Why attachments occur

In the Bible, the prophet Ecclesiastes declares that God has “set the world in their heart”, meaning he has created a tendency within us to become attached to the objects and ideas of the world. This instinct is our survival mechanism, a practical response to life on the material plane. Our faculties for acquisition and possession enable us to obtain food, shelter and other necessities, which in turn make it possible for us to live life for its highest purpose – seeking the Lord within. Over time, these instincts have become unbalanced and distorted. The faculty for acquisition has turned to greed, a compulsion to acquire more and more, way beyond the bounds of need. The instinct for possession has turned into an obsessive attachment to the people and objects acquired – we forget that they are gifts, believing instead that they belong to us.

But why exactly have our natural instincts come to dominate? The explanation lies in the illusion created by maya, the dominance of the mind, and the bondage of the soul. From the moment of its separation from the Lord, the soul became inextricably tied to the mind. On the material plane, both are engulfed in a veil of illusion and ignorance, a condition exacerbated by the mind’s relentless pursuit of sensual gratification despite the suffering that ensues. This lethal cocktail of attachment, egotism and maya means that the mind refuses to give up the very attachments that keep it and the soul from attaining liberation. The situation is compounded further as the mind mistakenly tries to mask the soul’s innate yearning with new attachments.

Consequences

The mind’s attachment to possessions and relationships have three profound consequences. The first is that we cannot escape the cycle of birth and death. In Quest for Light, Maharaj Charan Singh makes clear that even if we practise meditation regularly, our attachments will bring us back to the world. He unequivocally states: “You go where your attachments are and you reap what you sow. These are eternal laws which work in this creation and every soul is bound by them.” The law of karma is paramount. As well as governing the domain of action – as one sows, so one reaps – karmic law functions at the level of the mind by creating an indelible imprint of our entire mental activity in order that every idea, aspiration, desire is fulfilled. Since it is impossible to actualize our multitude of desires in one lifetime, karmic law dictates that we must take birth in another body. Our attachments therefore are responsible for keeping us imprisoned in the cycle of life and death.

Our coming back to the world is not pain-free and this constitutes the second effect. In Buddhist philosophy ‘suffering’ represents a core feature of human life and attachments constitute the primary source. This is not to deny that they may have provided pleasure and happiness for a short period but eventually all attachments, in one way or another, lead to suffering. The pain that we feel upon the death of a loved one is perhaps the clearest example of this.

Our continued separation from the Lord is by far the gravest consequence of all. Attachments make us forget the real purpose of human life. Spirituality is often another item to fit in a busy schedule, rendering concentration at the eye centre virtually impossible, and consequently our inner journey barely begins. Indeed, as recorded in the gospel of Saint Matthew, Jesus says that anyone who is attached primarily to the world is “unworthy of me”. In this context, ‘unworthy’ means we will continue to be bound by our attachments; we will therefore remain in the realm of birth and death, unable to find the spiritual form of the Master inside and thus unable to return to God.

The mystics’ sword: Truth and Love

To rise above our attachments, we must go to a mystic. In the gospel of Saint Matthew, Jesus states, “Think not that I am come to send peace on earth, I came not to send peace, but a sword.” And in the gospel of Saint John, he tell us, “For judgement I am come into this world, that they which see not might see; and that they which see might be made blind.” In these statements, Jesus is emphasizing that the role of the Master is to detach us from the world. Using the sword as a metaphor, he creates a vivid image of the mystics literally severing the roots of all our attachments. This they do by teaching us a spiritual exercise that liberates our soul, reuniting us with the Lord. So, when Jesus states that the mystics make blind those who can see, he means that because some of us are so attached to the world and have all but forgotten the Lord, the mystics impart the gift of love for the Lord, and it is this which finally quenches the desire for possessions and, in effect, makes us blind to materiality.

Parenthood and detachment

Where does this discussion leave us as parents? How do we reconcile the overwhelming love we feel for our children with the spiritual goal of detachment? The foundational principle of spirituality is that our essence is the same as the God that dwells within us – love. Therefore, it is natural for us to both give and receive love. When the mystics encourage us to live in the world without being of the world, they do not expect us to deny the love we feel for children or others. Given that we are driven by a powerful ego, it is love that helps us fulfil our obligations to them. Moreover, detachment cannot be forced – it will happen naturally as our meditation strengthens and love for the Master grows which, in turn, develops in relation to how much effort we put into our meditation.

Remembering the Lord brings us to the crux of what the mystics expect of us in relation to detachment. Whilst enjoying our time with the family, they impress upon us not to forget the Lord. This means practising meditation on a daily basis even when demands on our time are the greatest. In the early years of parenting, on some days this may mean a mere thirty minutes here or an hour there. The important point is to devote some time to meditation every day.

At our level of understanding, we typically view detachment as the end game. However, as our consciousness develops, we transcend the desire for detachment, realizing there was nothing to detach from since nothing ever belonged to us in the first place. As quoted in Concepts and Illusions, “Spiritual maturity lies in the readiness to let go of everything. The giving up is the first step. But the real giving up is in realizing that there is nothing to give up, for nothing is your own.” In other words, once we have removed the shackles of attachment, we will realize that the truth has always been with us.

Truth in a Nutshell

The Present Moment

Buddha was once asked, “What makes a person holy?” He replied, “Every hour is divided into a certain number of seconds and every second into a certain number of fractions. Anyone who is able to be totally present in each fraction of a second is holy.”

Similarly, a Japanese warrior was captured by his enemies and thrown into prison. At night he could not sleep for he was convinced that he would be tortured the next morning.

Then the words of his master came to his mind. “Tomorrow is not real. The only reality is now.”

So he came to the present – and fell asleep.

Anthony de Mello, The Song of the Bird

Mostly we are unhappy in thinking about what has passed, and our future is always bothering or worrying us. So, when we are absorbed in simran, we will be at least safe from all this unnecessary worry. We should, therefore, try to make use of our time in doing simran whenever we are free mentally. That has definite advantages.

Maharaj Charan Singh, Spiritual Perspectives, Vol. II

Feeling Funny

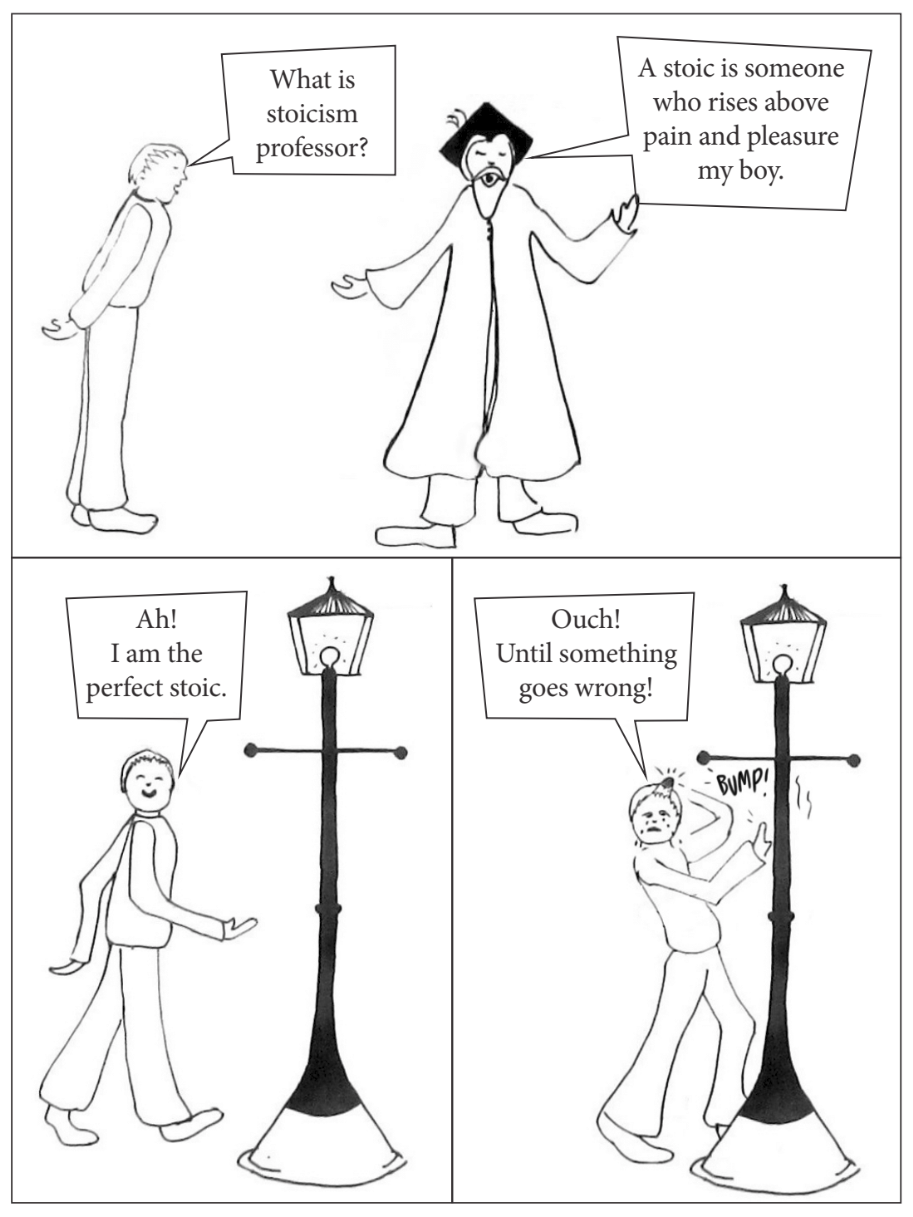

Theory and Reality

Are You Worried?

Worry is an intrinsic aspect of the human condition that is described by the Taoist sage Wei Po Yang as “preposterous.” One reason why worry is deemed ludicrous is that it presupposes knowledge of a situation that we simply do not possess. Fundamentally, though, the principal reason rendering worry preposterous is our own individual spiritual experience.

Many of us have yet to experience the inner sound or light. Nonetheless, most of us are able to recall at least one incident in which we have been conscious of the protection of the inner Master and, as he has steered us away from adversity, we found ourselves inwardly thanking him for his help in a difficult situation. As Maharaj Sawan Singh explains in Spiritual Gems:

[The Master] is always with us – within us – watches as a mother watches her child. So long as we are on this side of the focus, we do not see him working. But he is doing his duty. Your worries and cares are Master’s worries and cares. Leave them to him to deal with.

So, we find ourselves in a strange paradox. On the one hand, our personal experience of the Master’s guidance reassures us that he will look after us during difficult situations. On the other hand, whilst knowing that the Master has looked after us in the past, we continue to worry about the future.

What does worry tell us about ourselves?

Maharaj Charan Singh explains that there are two causes of our worry. As detailed in Spiritual Perspectives Vol. III, our endless desires constitute the first cause:

By nature, man is happy and contented. What makes us miserable is our wishes, our demands, our ambitions, our desires. When they are not fulfilled, we become miserable. But if we don’t have any desires, automatically we are happy. It is our desires which make us miserable, and all our desires can’t be fulfilled. Whatever is in your destiny will be fulfilled; what is not in your destiny – your worry will not be able to fulfil that desire.

So it is our desires that make us worry; if we were desireless, our anxiety about fulfilling them would not materialize. However, no matter how much we tell ourselves not to want things, it is impossible to achieve this by reason alone. At this level we are dominated by karma and it is only by eradicating karma that we will become completely desire-less, which in turn will free us from anxiety. As Maharaj Sawan Singh explains in The Dawn of Light, “Although in our heart we may persuade ourselves that we have eliminated desire, yet it is not correct, because as long as the karma is not washed away … it cannot be said that the practitioner has abandoned desire.”

Fear is the second cause of worry, as Maharaj Charan Singh makes clear in the following quotation from Spiritual Perspectives, Vol. III:

There is always fear of losing whatever the Lord may give us in this creation. If you have a lot of wealth, there’s always fear in your mind that the Lord has given me so much wealth in this world and I may lose it.… There is always a fear of losing even the best things we have of this life. As long as fear is at the base of our happiness, we can never be happy.

Paradoxically, it seems that sometimes we don’t even fully enjoy the happy times because, knowing that life can be precarious, we become anxious as to when and how our good situation will end. This negativity and worry suggests that our faith in the Master is weak. Maharaj Jagat Singh advises in The Science of the Soul, “Your worrying shows that you have no faith in the goodness of God or even in God himself. Let him accomplish things in his own way rather than in the way that you desire.”

How do we stop worrying?

Training the mind to live in the present is one way in which we help ourselves to stop worrying. We cannot change the past and we exercise little, if any, control over the future. All we have is the present moment. In Spiritual Perspectives, Vol. III, Maharaj Charan Singh explains:

We must live in the present. Every day has to be lived. So we should plan for a day and then live it thoroughly and happily, and attend to our meditation. That is the only way we can get out of these worldly worries and worldly problems.

The value of trying to take one day at a time, one task at a time, has been picked up by modern philosophers who call it ‘mindfulness.’ If we practise it, we will not only reduce our worries, but strengthen our mental muscles, which, in turn, will support our meditation.

Doing our best and leaving the results to the Lord is the second piece of advice Maharaj Charan Singh gives us to stop worrying. He says:

Brother, instead of worrying about the situation, one should try to do one’s best. With your best available intellect or reasoning or thinking or intuition – whatever you may have – do your best, then leave it to the Lord.… You have no other option.

Maharaj Charan Singh makes clear that having tried our hardest, we have no option but to leave the outcomes of life to the Lord, as our destiny has already been determined and no amount of worry will change this.Such surrender comes with consistent, dedicated meditation practice.

In an era characterized by individualism, narcissism, and conspicuous consumption, there is no method more effective than meditation to help us learn to accept rather than demand and that also stops us worrying, by increasing our faith in the Master.

You can’t change the course of events dictated by your destiny. But by obedience to the Master and attending to meditation you remain happy and relaxed as you go through it. You accept whatever comes your way as the grace of the Master. He is the helmsman of your life now, and he has only your happiness and best interest at heart. By his mercy he is bringing you to him as swiftly as possible to give you all he has. So worry has no place in a disciple’s heart.

Maharaj Charan Singh, Die to Live

The Patient Saint

A recluse lived under a large yew tree. Every day he spent much of his time praying to the Lord. After many years, he was visited by an angel who said it was his duty to report to the Lord on the progress of those who did their spiritual practice with devotion.

The recluse asked if the angel would find out when it would be his happy lot to meet the Lord. The angel agreed to do this and left on his mission.

Shortly afterwards the angel returned, and informed the recluse that he would not meet the Lord until many years had passed as there were needles on the yew tree above his head.

The recluse immediately began to dance for joy. The angel was very puzzled by this reaction.

“Do you understand that there are millions of needles on this tree?” he asked. “And that you will not meet the Lord until millions of years have passed?”

The recluse said he had understood this very clearly.

“Why then are you so happy?” asked the angel.

The recluse replied, “I am happy because at last I have received a reply from my Beloved, and he has promised that we shall indeed meet one day. When that meeting takes place is not important.”

At that very instant the Lord himself appeared and embraced the recluse. Surprised, the angel reproached the Lord, “You told me that the meeting wouldn’t happen for many years and now I look like a liar.”

The Lord responded, “These things are for ordinary men. When there is someone special who has transcended the laws of time and space within himself, then I also cast those laws aside”.

The Invitation

Imagine if the Master invited us to live with him at the Dera. Elated and excited, our entire focus would be directed towards making the necessary arrangements for our departure. Without hesitation we would drop commitments that previously seemed important.

But how do our imaginary actions compare to the way we respond on a daily basis to the real invitation issued by the Master – the one in which he waits for us to join him one-on-one at the eye centre? Few amongst us could claim that we approach our meditation sessions with the same level of zest and gratitude that we would if the Master had asked us to join him at the Dera. Maybe this is because organizing such a move, whilst requiring much effort, is easier than simply being still and silent so as to experience his presence. To put it another way, unlike a trip to the Dera which would require us to take clothes and other practical items, it is essential that when meditating we discard our worries, aspirations, and analyses of all that has passed and bring nothing with us..

Bringing nothing

If we were able to forget the outward part of ourselves during meditation and turn our attention inwards, we would begin to foster the kind of relationship with the Master that we currently try hard to create through darshan and physical contact. But bringing nothing, discarding our preoccupations with daily routines and desires, is the cornerstone of our spiritual struggle.

There is no complicated reason underpinning our difficulty. How we spend ninety percent of our day influences the ten percent we dedicate to meditation. It is impossible to change habits at the flick of a switch, least of all those that are deeply ingrained. Essentially, we cannot expect our mind to change its normal behaviour – chattering constantly – just because we want it to be quiet during meditation. On a daily basis then, we are confronted with a gap between our desire for spirituality and the actions of the mind. Over time, this gap is bound to test the enthusiasm of even the most determined seekers. However, instead of becoming frustrated or reproaching ourselves for lack of self-discipline, it would help to understand the nature of the mind so that we can bridge the gap and approach our daily meditation session with renewed interest and determination.

How to bring nothing

Like neuroscientists, the mystics view the mind as a muscle which, in effect, is driven by two forces: one is our conscience and the other is pleasure seeking. Currently, the mind is both helping and thwarting our spiritual development. Indeed, since our love and desire for spirituality originates in the mind, Maharaj Charan Singh counsels us in Spiritual Perspectives, Vol. I, to make it our best friend, emphasizing that we cannot progress further without doing so:

All your emotion, your devotion, your love to begin with are nothing but the outcome of mind. Mind is creating that love and devotion in you, and soul is taking advantage of it. So we have to win the friendship of the mind … and we have to give our mind a better pleasure than sensual pleasure.

By emphasizing that we need to make friends with the mind, Maharaj Charan Singh is encouraging us to train the mind to act in the interests of our spiritual welfare. The result will be that it no longer succumbs to the thoughts, feelings, emotions, or desires that make meditation harder. This requires vigilant self-monitoring, as Maharaj Sawan Singh explains in the following letter from Spiritual Gems:

Mind needs vigilance of a higher order than is given by parents in bringing up their children…. So long as it is not trained, it is our worst enemy; but when trained, it is the most faithful companion. And the point is that one has to train it to get the best out of it and to realize his spiritual origin.…

There is a proverb here: ‘If you are going fox hunting, go with the preparation of a lion hunter.’ The same applies to mind hunting. Every day one should be on the job with renewed determination.

There is a risk in discussions about ‘conquering’ the mind that it will assume a strength of mythical proportions. Whilst we should not underestimate its power, the above quotations are reassuring since they suggest that, with regular exercise, we can redirect the mind to act in ways that will support our spiritual development. Living in the moment by repeating simran throughout the day is one such exercise. This is the best way to stop fuelling our habit of compulsive thinking, which in turn will make it easier to quieten the mind during meditation. As explained in Living Meditation:

The present moment is the most valuable thing there is. Nothing happens tomorrow, nothing happens yesterday, everything always happens now. In fact, the ‘now’ is the only time there is. It is impossible for us to do or to think outside the present moment.

A further way in which we can train the mind to promote our spiritual progress is by learning to accept all that passes without worrying about the future or feeling guilty about the past. One exercise to achieve this equanimity would be to identify how events that we deem to be negative may assist our spiritual efforts in the long-term. The proverb ‘each cloud has a silver lining’ is designed to encourage us to find the positive aspect of the gloomiest of situations. As well as identifying the positive aspect in a material sense, we could look for the spiritual benefits. For example, not getting a promotion may mean less work and more energy to concentrate on Sant Mat. Being outbid on a house may prove more conducive to concentration as one is not saddled with a large debt and a lifetime of anxiety and work to pay it off.

In this way, we begin to develop an attitude whereby we view everything through the prism of how it affects our spiritual life. This attitude may be enhanced further by assessing how every action or inaction (mundane or otherwise) will affect our meditation practice. For example, avoiding a chore and watching the television will provide instant gratification but may become an issue if we keep thinking about the chore during meditation. If we are involved in a quarrel, regardless of who is right or wrong, we should be the first to make up, for no other reason than we do not want to think about it during meditation.

Meditation then is not an activity confined to two and a half hours a day. Preparation beforehand is equally as important. Indeed, following a spiritual path is difficult specifically because the two are inextricably linked. As noted in a thirteenth-century text for nuns, The Ancren Riwle, “Let no one think that he can ascend to the stars with luxurious ease.” However, we are not alone. The inner Master is always with us, helping us to reach the eye centre and beyond as swiftly as possible, rewarding our most paltry efforts ten times over. The elation we would feel if the Master asked us to join him at the Dera will, no doubt, pale into comparison when we finally become conscious of travelling with him inside to reach our final destination.

What about Demons?

Stories, myths, and legends about demons and dragons are found in all cultures. In Europe, the tale of Saint George, who slayed a dragon and saved a distressed maiden, has been popular since mediaeval times, and many countries claim this legendary character as their patron saint.

Demons fascinate us and are particularly prominent in electronic games. Beyond cultural representation, however, do demons really exist or are they imaginary creations of the mind? If they exist, does our faith as satsangis protect us from them?

The Oxford English Dictionary defines ‘demon’ as an ‘evil spirit’ or ‘devil’. As an acknowledgement of the existence of a negative power, reference to them in one form or another appears in virtually all religions and spiritual traditions. Thus, the Greek mystics spoke of Discord, the Christians and Jews talk of Satan and the devil, Muslims refer to Shaytān, whilst a ‘lord of death’ is depicted in Hindu mythology.

A long-standing question puzzling theologians is whether a negative power is both independent of, and opposed to God, in which case God cannot be absolute; or if the negative power is acting within the will of the God, in which case why does God allow it?

In mysticism, the conundrum does not arise. Originating from God, the negative power is his servant. The Path of the Masters explains that, compared to humanity, the so-called negative power, as manifest on the inner planes, is “full of light, goodness, [and] wisdom”, and is fulfilling a “divine and loving purpose”. The Sant Mat teachings refer to the negative power as the Universal Mind, sometimes personified as Kal. The Universal Mind is viewed as the architect of time and space and the law of karma – the strict system of justice that confines souls to the realms of mind and matter. As explained in The Treasury of Mystic Terms, Vol. VI, the Universal Mind is the “prime weaver of the web of illusion”, the “integrating force between all the seemingly individual minds of the multitude of creatures”, and the “power that must be surmounted before the soul can gain freedom from birth and death and return to God.” The individual human mind, the body and the senses are all aspects of the Universal Mind and, as such, operate as agents of the negative power. Maharaj Sawan Singh explains in Spiritual Gems:

Individual mind is Kal on a small scale. It is Kal’s agent, attached to every soul to keep it out from the eye focus and keep it entangled in this world. No individual is at peace with himself and no one is happy. In ignorance, doubt and fear, men go about.… The world is a plaything of Kal.

Although the soul is a drop of the divine essence and should control the mind, in practice the soul is dominated by the mind and the mind is dominated by the senses. The Universal Mind is able to keep souls captive in two ways: by occupying the attention of the mind with the varied phenomena and activities of the creation, and also through the inescapable, exacting law of karma. The souls themselves are therefore responsible for their own suffering and bondage.

In mysticism then, the negative power is not an external power but resides within, and it is from there that the battle to free the soul from the clutches of the mind must take place. The only way to purify the negative tendencies of the individual mind and escape the negative power is through a mystical teacher who represents in human form the power sustaining the creation – the Word. By focusing our attention on the Master and following his instructions, we leave no room for demons.

Feeling Upset

We all do our best to follow the Master’s instructions about remaining positive when events take a different turn from the one we desired, but admittedly there are times when we find it hard not to become upset. Rather than dwelling on our disappointment, it might be easier to accept how things have turned out if, as suggested by Maharaj Charan Singh in Die to Live, we view acceptance – or what the mystics call ‘living in the will of the Lord’ – as a form of seva:

We have to face situations at every step in this life, and at every step in this life we have to explain to our mind, “You have to accept whatever comes in your fate and accept it smilingly, cheerfully. Why grumble?” It’s a constant training of the mind. This is also doing service, because that will help us in meditation.

Sometimes we become upset when people act negatively towards us. Whilst repeating simran is the best way to stop us thinking about the slight, we can also draw comfort from guidance provided in the spiritual literature. In Quest for Light, Maharaj Charan Singh encourages us to accept the will of the Lord:

Nobody ever does us any good or bad thing, nor can any person offer us insult or bestow honour on us. The Master moves the strings from inside and makes people behave towards us according to our karmas. All insults or loving attention come to us as a result of our own actions – sometimes from a previous life and sometimes from the present life. So do not take too much to heart the behaviour of other people towards you.

Receiving criticism is another situation many of us often find upsetting. Whilst our initial reaction may be one of hurt pride or even anger, the Master advises us to use this as an opportunity to improve ourselves. It is to our benefit if we view criticism as part of the learning and cleansing process we are undergoing, particularly if, as Maharaj Charan Singh explains in Spiritual Perspectives, Vol III:

Brother, we should not mind anybody’s criticism at all. I can tell you, critics are the best guide in life. We should always keep our ears and eyes open to our critics. We must weigh their criticism without any ill will towards them. If it has any weight, we should try to learn from that criticism.… Without our critics, we would never be conscious of our shortcomings, our weaknesses. They are very essential for us to improve ourselves.

We can all relate to at least one of the aforementioned scenarios. As spiritual seekers, it is not uncommon for us to feel doubly upset – by the situation itself and for not remaining positive as advised by the Master. However, since we are at the early stages of learning humility, we should not become disheartened. In fact, feelings of disappointment and hurt are a good reminder of how much we need to practise meditation. Every time we repeat the holy Names attentively, we are trying to awaken our higher consciousness. Eventually, when we reach the eye centre and our attention is turned inwards, external circumstances will no longer upset us.

Happy, Relaxed and Divine

Maharaj Charan Singh recalls the Great Master’s humour : An extract from Spiritual Heritage:

Nobody could match Great Master’s humour. There was no limit to his humour. And he was also practical, I would say, in the sense that sometimes, when he found that the subject matter had become very serious – and naturally, it reflects on people’s faces when you talk about hell and punishment and misery, because these are not very pleasant; and everybody looks within and knows what he has done and that he will have to suffer for all that, so of course one cannot smile about it. So when he found that people had become very sad and serious, just to erase that effect he would finish with an amusing anecdote or story, or say something that would make everybody roar with laughter and forget everything he had said!

He would say what he wanted to say, fearlessly…. He never compromised with the teachings or in his explanations; but still, at the end he wanted everybody to get up from satsang absolutely relaxed and happy, without any tension, and he always managed it.… We always came out of satsang with a smile.

He used to tell a lot of stories.…[In satsang and] even in his conversation, when talking in a family group and trying to explain certain things to us – that we should not behave like this, or that we should study and work hard – would tell us one or two stories to convince us of what he was trying to say. That was his approach: a very humorous and smiling approach, and always very loving.

I remember one incident concerning my younger brother and myself. It is generally a custom in India for the boys in the family to press the legs of the elderly men in the evening when they are tired. My brother and I often used to do it after we got back from college. The Great Master would lie down and we would press his legs. On one occasion, I was pressing one leg and my brother was pressing the other. He was quite over-enthusiastic as a boy, and after doing his leg, he started on the other leg also, which I was pressing. So sometimes I would touch his hand, saying, “Do not touch this leg, this is my leg!” And sometimes he would do it again. But while striking each other, by mistake we would also strike Maharaj Ji’s legs.

Maharaj Ji went on watching, and all the while he was talking to Sardar Bhagat Singh and other people about some of the Dera lands.… When he thought that we had started striking his leg too much, he got up, sat in a chair and told a story to the four or five people sitting there:

There was once a sadhu who had two disciples, and they used to press one leg each. But one disciple was very naughty, and while pressing his leg, he would try to do the other leg also. And the other disciple would not let him. So they began striking the other one’s leg and began to quarrel.

The first said: “I will break ‘your’ leg.”

And the second said: “I’ll break ‘your’ leg.”

And then they pulled out bamboos and beat that sadhu so much that they crippled him!

After telling this story, Maharaj Ji smilingly said: “My children have not reached that stage yet. They are only striking with their hands, not with bamboo sticks!” And we were just sitting there at his feet.

So his whole approach was like that, whether family matters or in satsang matters.

Book Review

The Poems of Hafez

Translated by Reza Ordoubadian

Publisher:: Bethesda, MD: Ibex Publishers, 2006

ISBN: 1 – 58814 – 019 – 9

Hafez (1315–1390 CE) is considered to be among the world’s greatest poets, alongside Jalal al – Din Rumi, who lived a century after him. But, in Iran, Hafez has always been distinguished as the people’s poet. Even now, more than six hundred years after his death, almost everyone in Iran can recite his poetry. His verse is so rich in metaphor and imagery that it can be interpreted for many tastes – as pithy worldly wisdom, as the poetry of passionate romantic love, or as revealing the heights of spiritual love for God and one’s spiritual guide (murshid).

Translation of these evocative poems into English is a challenging task. Hafez used highly structured metrical forms, with sometimes three rhymes in a single line. Many words in the original Persian have no easy English equivalent. Attempts at literal translations are often stilted, even incomprehensible. Only the rare translation can be faithful to Hafez’s meaning and suggestive of its poetic form, and yet also speak, as Hafez’s poetry unfailingly does, to both imagination and heart.

The Poems of Hafez by Reza Ordoubadian is a skillful, graceful, and authentic translation of 202 poems. Ordoubadian manages to capture both Hafez’s lyrical genius and his profound spiritual insight. Ordoubadian seems especially qualified to work with Hafez. A native Iranian well versed in the literature of his country, he has spent his career teaching English literature in the United States. But, along with his academic preparation, he is adept at poetry, so that his poems often capture not only the verbal meanings but also the melody of the original. He provides extensive notes at the back of the book to explain subtleties in the original Persian, the choices he made as translator, and some cultural background needed to fully comprehend the poems.

Even single lines of Hafez can illumine one’s spiritual understanding. Here are some examples of such lines, as rendered by Ordoubadian:

Though old and frail and tired of life,

Remembering your face turns me into a youth again.Hafez, your duty is uttering prayers – that is all –

Never mind if God hears them or not!On the way what comes to the disciple is a blessing.

In the straight path of truth, no one is lost.Why turn away from the Master’s threshold?

Our fortune is in that house, and the answer is at that door.

Hafez is not a poet for the faint of heart.

Whatever we thought, it was a mistake.

Moonless nights, fear of waves, horrid whirlwinds,

How could they know our lot – those landlubbers!Hence nothing but resignation and appreciation of the Master:

my heart inured to pain, farewell to healing, I spoke.

One of the great themes of Hafez is what it feels like to be divided; to be part in love with God, and part sunk in the material world:

Show me a way out of the darkness of my bewilderment!

In the sea of sinfulness I am drowned in a hundred ways:

Acquainted with love, I’m among the graced…

Deep sea and mountains on my path, and I, tired and weak,…

Help me with my resolution.

My heart away from the doors of your mansion;

Yet soul and heart, I am a resident of your mien!Blessed God! What temptations crowd our heads!

Who resides inside my weary heart?I remain full of passion and fight!

Discord rules my heart: O where are you musician!

Sing your tune: bring harmony…

Disinclined with the affairs of this world;

only the beauty of your face opens my eyes.

Bereft of sleep, heart breaking with empty thought,

Hung-over for a thousand nights! Where is the tavern?

Hafez also offers wonderful descriptions of the long-awaited blissful union of soul with God:

The day of separation and the night of absence have ended…

The dawn of hope, that mystical veil of those who retire to pray:

Tell them to come out, the darkness of their night has ended…

Although no one counted Hafez much, praise God,

All that boundless burden and reckoning has ended.

Reza Ordoubadian is clear and strong is in his treatment of Hafez’s words of comfort and consolation to the struggling soul:

This heart, mournful, it will heal, do not despair –

This head, frenzied, it will heal – do not grieve.

Perchance heaven denies our desires for a day – or two.

There is no constancy to the notion of time – do not grieve.Last dawn I told my story to the wind, my yearning;

a voice declared, “Be secure in the grace of God.”

Morning prayers, sighs at night:

Key to unlocking the treasure gates.

Follow this path to be united with the object of love.

With many translations and even renditions of Hafez available, we can seek the one that best speaks to our heart, mind and soul. For example, here is a single line as translated by three respected translators. Ordoubadian writes, “O You, the royal falcon, worthy to sit on the tree of life – your presence in this humble place is a cause for lamentation. You are summoned by the heavenly voices from the throne.” In the book, The Green Sea of Heaven: 50 Ghazals from the Divan of Hafez, by Elizabeth T. Gray Jr., Gray writes, “O royal falcon of keen vision. Perched in the tree of Heaven, your nest is not this corner filled with suffering. They whistle to recall you to the battlements of Heaven.” An edgier version is offered by Robert Bly in “The Angels Knocking on the Tavern Door: 30 Poems by Hafez”: “Your perch is on the lote tree in paradise. Oh, wide-seeing hawk, what are you doing crouching in this mop closet of calamity?”

The poets of mysticism offer the seeker companionship on the journey, and fresh ways to understand one’s blessings and challenges. Hafez is unparalleled in his ability to remind us that we are loved, and that love is demanding, occasionally frustrating, and always bewildering. Most important, Hafez reminds us that God’s love is our unfailing destination.

Book reviews express the opinions of the reviewers and not of the publisher.