Download | Print | Archives

July 2018

There Is No One as Brave as a Saint

Describing the Indescribable

Except the Lord

The Image of God

Truth in a Nutshell

Another Side of Meditation

Love in Action

Benefits of Satsang

An Unchanging Happiness

Undoing the Knot

Living with a Serious Illness

Why Question?

Food for Thought

Those Who Bend Are Great

Under the Master’s Protection

Don’t Expect

Book Review

Mindfulness: A Practical Guide to Awakening …

Start scrolling the issue:

There Is No One as Brave as a Saint

There is no one as brave as a saint.

He has vanquished attachment

along with its entire army,

so perfect and tranquil is he.

By donning the shield of forgiveness

and wielding the sword of truth,

he defeats the troops of ritual and delusion –

moment to moment, again and again.

Making his attention the arrow, his heart the quiver

and contemplation his bow, he pulls the string

and hits the mark with the hand of love.

With the dagger of wisdom and discrimination,

and the spear of his sweet mystic words,

he pierces the hearts of true seekers

with his enchanting discourse.

With great fervour, he listens to the ceaseless Melody.

His feet never wander from the path

leading to the Inaccessible,

even if he is cut to pieces.

With a joyful heart and the anticipation

of meeting the Beloved,

he approaches the field of Sunn.

O Charandas, says Sukhdev,

such a one attains the immortal realm.

Sant Charandas

Describing the Indescribable

From the beginning of my life

I have been looking for your face

but today I have seen it.

Today I have seen the charm, the beauty,

the unfathomable grace of the face that I was looking for.

Today I have found you.I am bewildered by the magnificence of your beauty

and wish to see you with a hundred eyes.

My heart has burned with passion

and has searched forever

for this wondrous beauty that I now behold.

I am ashamed to call this love human

and afraid of God to call it divine.Your fragrant breath like the morning breeze

has come to the stillness of the garden.

You have breathed new life into me.

Every fibre of my being is in love with you.

Your effulgence has lit a fire in my heart

and you have made radiant for me the earth and sky.

Love Poems of Rumi, ed. Deepak Chopra

The words of the poem by Rumi serve to remind us of the strength of our spiritual longing to come face to face with our Master inside.

It takes a long time, much dedication, and the Master’s grace to reach this stage. Yet we are told that those initiates who do daily battle with the mind and withdraw mind and soul from all outside phenomena, concentrating at the eye centre, will reach the inner stars, sun and moon. Beyond them will appear the Radiant Form of the Master. We are wonder-struck to hear descriptions of the beautiful physical form of the Master but, if we manifest him within, we will find him a thousand times more beautiful. The mystic poetry of Rumi is nothing more than an attempt to describe the indescribable – the surprising, intimate, and ultimately dazzling nature of his experience. Another Persian mystic, Qajar Hafiz writes:

O Beloved, I have heard many a tale about your wondrous beauty; but now that I have beheld you within, I see that you are really a thousand times more wonderful than the tales depict you. The whole night his refulgence filled my heart with light. What a bold thief he is to come in the darkness but with what an aura of radiance he comes!

As quoted in Philosophy of the Masters, Vol. I

Maharaj Sawan Singh talks about the same experience in Philosophy of the Masters, Vol. V:

When the inner eye is opened, one realizes that the Master is the one before whom all should prostrate themselves. He is the life of the universe. He is Truth personified, or Reality in human form.… There is no one better than he.

Rumi attempts to describe the greatness of his Master, Shams-e-Tabriz, in the following words, using in parallel with the beautiful epithets of sun and moon some unexpected everyday imagery:

You who are sun and moon, you who are honey and sugar, you who are mother and father, no lineage have I seen but you. O infinite love, O divine manifestation, you are both stay and refuge; an epithet equal to you I have not heard. We are iron filings and your love is the magnet; you are the source of all questing.… Be silent, brother, dismiss learning and culture … Shams-e Haqq-e Tabriz, source of the source of souls, without the Basra of your being, no date have I ever known.

Mystical Poems of Rumi Vol 2, tr. by A.J. Arberry

In medieval times, Basra in Iraq was famous for its excellent dates, so what Rumi is in effect saying is that if he had not met his Master he would not have enjoyed the sweet taste of spiritual experience. Surely we can all relate to this sentiment.

Yet most of us shut our eyes and find nothing but darkness within, more pronounced than a completely moonless night. Why is this? It is because the soul currents, tangled with mind, are spread out through the universe. Rather than burning with passion for spirituality, we have fallen in love with the tempting illusions of the world. If we want to emulate Hafiz by becoming intoxicated with the beautiful face of Truth, we must be prepared to recognize the world for what it really is, and turn away from it.

Note how Rumi, in the piece quoted above, puts learning and culture into perspective. In this world they are held in high esteem but for the seeker on a spiritual path they can be obstacles. The problem with adding more and more to our store of knowledge and experience is that none of it adds up to spiritual understanding. Instead, as we strengthen our attachment to our so-called learning and culture, we neglect our spiritual effort.

There is no doubt about it: it is not easy to live in this world. There is enormous pressure on us to relish its delights. It takes a mystic to see through it and reveal the reality. Rumi says:

The world was no festival for me;

I beheld its ugliness, that yellow wanton puts rouge on her face.

Go; wash your hands of her, Sufi of well-washed face;

Shave your heart of her, man of the shaven head!

Unlucky and heavy of soul is he who seeks fortune from her;

Come to our aid, Beloved, amongst the heavy-hearted,

You who brought us into this wheel out of non-existence.

Rumi depicts the world as unclean. It is a lurid courtesan who appears attractive only thanks to the deceptive effects of cosmetics. Without the Master’s help our mind cannot see through the apparent charms of the world, so we find ourselves spinning on the wheel of chaurasi (living, dying, and being born again according to our karmas). We are functioning on the mind’s autopilot and that pulls us back to the creation over and over again. That is why only our Creator –“You who brought us into this wheel” – can help us. Knowing that we need his help, he sends his beloved Sons into the world to come to our aid.

Rumi says, “We are iron filings and your love is the magnet.” He is telling us that the pull of the Master becomes irresistible to true seekers. We meet a Master, connect with him emotionally, and this sense of connection inspires us to put his teachings into practice. Doing the practice equates to the iron filing being held within the radius of the magnet. At this point we are flicking the switch to the soul’s autopilot – longing for the Lord – and our journey to the eye centre begins.

If we want the real bliss that Sant Mat offers, we must flick that switch rather than remain satisfied with the tawdry pleasures of the material world.

Difficulties will not disappear but they will become bearable when we keep the Lord and our purpose central to our lives. In Spiritual Gems Maharaj Sawan Singh writes:

We are lucky that we are human beings and have the opportunity to go in now, in this life. Why leave it to uncertain future? So with love and faith in the Master, keep on with your repetition and listening to the sound current.

Although the experience is ultimately indescribable, it is achievable.

The human form of the Master is “the Word made flesh.” It is the same Word that was in the beginning, was with God, and was God, and created all things, as is also mentioned in the Bible (John 1:1, 2, 3).When we see him within, we see him in the form of the Master who initiated us. Inside, you will see his form as you saw him in the human body outside, but that form will have a peculiar brilliance and radiance that cannot be seen with the physical eye, nor can one even imagine the effulgence of the Radiant Form within.

Maharaj Charan Singh, Divine Light

Except the Lord

Many years ago, the school I attended had its own school song which we used to sing on special occasions and at religious services. This song was based on a psalm in the Bible which contains the following lines:

Except the Lord build the house, he labours in vain who builds it.

Except the Lord keep the city, the watchman wakes in vain.

The city that is referred to was probably a walled city and it would have had gates that were shut and locked at night, but even so, because there was always a danger of attack from unfriendly neighbours, a watchman would have been appointed to warn everyone in case of need.

The house and the city stand for anything that we do in life, all our undertakings, which succeed or fail according to the will of the Lord. If we take the example of building a house: we may go into every little detail of the architect’s credentials; we may appoint the very best builder and choose the finest materials, seemingly leaving nothing to chance. But if it’s not part of the Lord’s plan that the house be built, it will not be built. On the other hand, when it is part of the Lord’s plan, nothing can effectively stand in its way. It’s quite hard for us to understand this. The schemes we have – we think that we are originating them, we are doing them. We feel that if they succeed, it’s because we have been clever; if they fail, we must have done something wrong. Either way, we take everything on our own shoulders, whereas the mystics tell us that not a leaf stirs without God’s command.

In The Master Answers, Maharaj Charan Singh says: “We are all just like puppets who are dancing and the strings are being pulled by him according to our karmas. The only difference is that the realized souls know that he is pulling the strings and the unrealized souls think that they are dancing by their own effort.”

One particular verse of the song has remained in my mind. I often remember it, partly because it gives the example of a watchman and that may remind us of RSSB properties where sevadars watch all night to keep the premises safe:

From those to whom God giveth much,

The more requireth he.

And if our outward path is smooth,

More faithful should we be.

For men, not walls, a city makes,

The men of heart and brain

– Except the Lord the city keeps,

The watchman wakes in vain.

Of course although it gives the example of watchmen, it’s not just about them, it’s about all of us. What does God give us? Well, just about everything – our consciousness, our human life, all the facilities we get, all the support we have. As satsangis, we are given the priceless opportunity to meet a true Master, have his company, receive initiation and the opportunity to meditate and do seva. All these are his gifts.

So what does he require of us? Baba Ji once discussed this very point in a Q&A session: what can we give to the Lord who gives us so much? The Master said that you always try to give someone something they haven’t got. So if someone doesn’t have a garden, you might take them nice flowers from your garden, or if they don’t have much time for cooking you might take them a cake. But since the Lord has everything and has created everything and given us all we have, what can we possibly give him?

It is our exaggerated sense of self, that we identify with, that we should give up to the Lord. Our ego is the creation of mind. So ego is what we should give to the Lord. Now the ego may not sound like a very good gift – but we are told that he won’t refuse it. Actually, that’s what he wants most of all from us – for us to abandon our sense of I-ness and just merge our will with his will. We can do that by remembering him. Kabir Sahib, quoted in Philosophy of the Masters, Vol. I, says:

One should remember one’s simran

in the same way as a passionate lover remembers his love

at all times of the day and night,

and forgets her not even for a single moment.

We show our gratitude by remembering him, and remembering him will bring us in line with his will, whatever it may be.

As satsangis, remembrance takes a practical form. We’re asked, when we’re initiated, to start meditating and to build that meditation practice up to two and a half hours a day. It’s probably not something that we can do all at once. So we start with what we can do, perhaps half an hour morning and evening and, remaining faithful day after day, slowly build from there.

In addition, after initiation, the Master suggests that we try to keep our mind under control during our daytime activities also. And we use simran, or the repetition of the five holy names, for this as well. We can do simran when we’re carrying out any activities that don’t actually require the full attention of our mind – things like preparing food, cleaning the car, waiting in a queue, or travelling to work. The advantages of this are many. Firstly, we find it much easier to concentrate at the time of meditation because our attention is already hovering at the eye centre; it’s not scattered out. Secondly, we haven’t lost energy in what Baba Ji calls “reacting” to things that have happened during the day, so we have more energy to wake up early to meditate. Thirdly, we lead a happier life because instead of worrying about things in the future or regretting things in the past, we are living in the here and now, just repeating those names.

The song suggests that “if our outward path is smooth, more faithful should we be.” We all go through a mixture of good and bad while here in this life. In outward terms, the good could include having good health, enough money for our needs and no overwhelming family worries, and the bad might be physical suffering, sorrows, responsibilities, and a difficult, demanding job.

If things are smooth for us, that is not the time to be lazy. We should give full attention to the path because, for example, it’s much easier to sit in meditation with a healthy body than with a body in pain or with a mind distracted by worldly cares. However, we should actually meditate at all times because in pain and sorrow, it is our only help.

Kabir Sahib, in his verses, urges us to do simran in happy times and then the unhappy times will never come. He doesn’t mean that bad karmas won’t arise – they will. But if we have become accustomed to doing simran in the happy times, then our attention will be so caught up in that bliss that it will carry us through the unhappy times – the bad times will have no effect on us.

When our meditation, our remembrance, begins to work, then in the words of Maharaj Charan Singh, “all the good qualities of a human being come in us just like cream on milk”. We don’t have to struggle for those qualities, they just emerge.

The song points out that in a community of people it’s not the buildings and the walls of the city that are important. Of course they are important in their way; having good buildings, good facilities, enables people to congregate in comfort. But the essential thing that makes a community is the people:

For men, not walls, a city makes,

The men of heart and brain.

In the same way, in the sangat, it’s our human and spiritual values that count. It’s how we interact with one another, how we use our brains to accomplish tasks, solve problems, carry out instructions, give advice and at the same time manage to listen, deal with difficult situations, even accept failure sometimes, by using our hearts.

We can be these people of “heart and brain” – a mature sangat, a loving sangat, only if we are faithful to the Lord and Master and remember that he is the one who really keeps our city, his sangat. Nothing we could do would be of any use if he was not directing it:

– Except the Lord the city keeps,

The watchman wakes in vain.

The Image of God

Man is the highest form of creation, including the angels. Man is the image of God. The Creator and all his creation are within him, and he has been given the privilege of meeting his Creator while alive. And this is the aim of coming into human life.

The whole secret is in the part of the head above the eyes. The “Way” to meet the Creator is also within man, and this “Way” is the basis of all important religions; but their followers are ignorant of it. They are content with rituals, ceremonies, reading of scriptures and prayers, doing charities, living a chaste life, working for the social and mental uplift of humanity – thereby feeling virtuous – but expect salvation as a reward after death. This is unwarranted.

The “Way” is the “Word” in the Bible, the “Kalma” of Prophet Mohammed, the “Shabd”, “Nam”, “Dhun”, “Akash Bani”, and so forth in Hinduism, and the “Nad” of the Vedas. These words are synonymous and refer to the same fundamental essence – the Voice of God – which is going on all the time within us; and we have the capacity to hear it when the attention is held within, instead of letting it run out in the external world.

There is no artificiality in it. It is not man-made. It sustains our life. It sustains the whole Creation. The Gospel of Saint John has attempted to explain it in terms of human experience in Chapter 1, verses 1-4. The Word is the design of the Creator, intended for man to catch hold of it from the eye centre and follow it right up to its origin, and thereby become God-like.

Maharaj Sawan Singh, Spiritual Gems

Truth in a Nutshell

Rich and Poor

Rabbi Moshe Leib said:

How easy it is for a poor man to depend on God! What else has he to depend on? And how hard it is for a rich man to depend on God! All his possessions call out to him: ‘Depend on us!’

Martin Buber, Tales of the Hasidim, Part II, The Later Masters

If we are attached to the world, whether we have made any spiritual progress or not, or even if we have made some spiritual progress, but if we have very strong desires, strong attachments to the world, then we may very likely be pulled back to the level of those desires – to the level of those attachments.

Actually, it is attachment which brings us back; it pulls us back to the world. But we can only detach ourselves from these attachments or from these desires when we are able to attach ourselves to that Holy Spirit within ourselves. Without the help of that Holy Spirit, that Shabd, that Nam, it’s very difficult for us to detach ourself from this world.

Maharaj Charan Singh, Thus Saith the Master

Another Side of Meditation

There seems to come a point in the journey of many satsangis when meditation is less than appealing. We tend to refer to this as a ‘dry’ period. The mind makes us think that there are a thousand better things we could be doing instead of meditation. Perhaps we could make a million before we hover over the edge of our grave? Or could we snag a top of the range, diamond studded, chrome on everything, designed-to-impress automobile? Or should we simply kick back on the sofa and binge-watch Netflix? It’s amazing how things that previously held no interest for us suddenly become endlessly fascinating when it’s time to sit. For instance, sleep seems to hold a compelling attraction – even if we’ve just snored our way through a long mid-winter snooze fest.

Aren’t the Masters asking a lot of us? They are essentially beckoning us to rise above our humanity: our nobility and pettiness, our selflessness and selfishness, the endlessly surging ocean of desires that currently define us.

At first we embrace the path with the excitement and vigour of little puppies. The Master issues a siren call to the soul and it touches a yearning so deep and sometimes so hidden that we can barely articulate a response – but respond we do.

Once initiated, we start meditating with great enthusiasm. But when that wild untamed mind of ours does everything in our meditation period but keep still, the effort begins to seem more like drudgery. Confronted by this wall of resistance, we begin to retreat from the path; the world, which meditation held at bay like a gentle tide lapping at our feet, quickly becomes a large wave, followed by another wave and another. Before we know what’s happened we’re submerged in our little lives and rather than meditation being a priority, it becomes a footnote in an endless list of things to do.

At this point perhaps, when we think of meditation, we feel a sentiment that the seventeenth-century English metaphysical poet, Andrew Marvell, expressed so well. In a bid to woo a reticent lover he wrote:

Had we but world enough and time …

My vegetable love should grow

Vaster than empires, and more slow …

Marvell is saying that if time wasn’t so fleeting, he would woo his love at a pace as slow and gentle as that of unfolding vegetation, and that empires could pass in the meantime. It wouldn’t matter. But the trouble is, he doesn’t have that length of time.

Like the poet, it’s hard not to feel impatient. The rate of progress in meditation seems to be infinitesimally slow and as a result many of us lapse into an attitude of indifference to it.

We’ve read that the saints can take our consciousness up to the eye centre in a second if they so wish; that even a particle of their power could set this cosmos spinning in another direction; that all we need to do is live our life and when we die, the Master will take us in, up and home. And so we abandon the necessary effort of meditation and settle for the theory. For us it may seem to be the easiest option. But we pay a price.

Our negative tendencies begin to harden; the invisible tendrils of greed, lust, vanity and envy slowly and almost imperceptibly take over our lives until we find ourselves with feet that feel like they’re firmly cemented in the world.

We might see people suffering some terrible adversity and unfeelingly dismiss it as karma – but are we at that level at which we can see the reality of karma, or are we just parroting a theory?

We’re unable to face the storms of life without reacting in ways that are ultimately detrimental to ourselves and those around us; perhaps we lash out in anger, perhaps we bury ourselves in greed or throw ourselves into fruitless endeavours. Ultimately we lose our balance.

Meditation is an incredibly powerful act. It cleanses us at a deep, unseen level; it confers a subtlety of perception; it refines our being, moving us away from our instinctive, animal-like nature to a state of grace. It lets the soul shine. But of course it’s difficult. Meditation goes against the very grain of this world. It’s anathema to everything that exists in the physical creation.

You can sit in a country field and soak up the energy and stillness of nature; it’s a soothing thing to do. But in reality nothing is still. Trees are endlessly producing cells, water is coursing through sapwood to nourish and replenish interiors, embryos are growing in wheat and the soil is home to millions of insects digging, scurrying and eating one another to survive.

Meditation on the other hand is a pure act of attempted stillness – it is simple, focused concentration. It generates an energy we can’t see, one which will propel us inwards and upwards when the time is right.

Of course we’re going to struggle; we’re going to hit those dry moments and we’re also going to feel disheartened at times. This is inevitable; it’s part of the journey. But it’s our duty to keep going.

In life some of us will suffer seemingly terrible adversities; others may experience great worldly triumphs, while many of us may settle into some sort of middle ground.

But whatever our circumstances, meditation helps keep everything in perspective and, if we continue in our endeavours, not only will we realize the wisdom of Shakespeare’s lines from Macbeth, we will also experience it directly:

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more: it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

This is the power of meditation. It opens our eyes. We begin to see things for what they are – not negatively, just realistically. As Shakespeare hints, the world, our being and actions take on a dreamlike quality. The world seems to have as much substance as a wisp of smoke.

A joyful perception enters our being, perhaps slowly and sporadically at first, but it begins to take root and grow. We begin to understand that ultimately nothing really matters except meditation and the Master.

If we don’t do our meditation, we rob ourselves of this sublime and subtle treasure and do a great disservice to our Master. We slow down our journey and unwittingly create obstacles for ourselves. So let’s recognize those ‘dry’ periods for what they are – arid and featureless terrains that must be passed through in order to reach the lush and elevating pastures that quench our soul’s thirst for freedom… and home.

Love in Action

We all find that some occasions in our lives become engraved on memory. The events that are described below are engraved on mine because of three things that they so vividly illustrated.

It was in November 1997 that Baba Ji invited the foreign visitors in Dera to a satsang in Moga, Punjab, warning that it wouldn’t be easy. Many volunteered, really looking forward to the chance of accompanying our Master to this large programme outside the Dera. And it wasn’t easy because shortly after Baba Ji started the satsang the heavens opened and torrential rain flooded everywhere. Baba Ji interrupted his satsang to advise the restless sangat that they were already wet, they might as well stay sitting!

There is a popular song which runs, “I beg your pardon, I never promised you a rose garden. Along with the sunshine, there’s gotta be a little rain sometime.” Well, we certainly got our rain that day and I guess I learned that satsang, like life, isn’t necessarily a comfortable experience – let’s just stick it out!

The foreigners were sitting on both sides of the dais upon which Baba Ji was sitting to give the discourse: men on one side and women on the other. As we sat, the water rose higher and higher, not able to flow away because of the plastic sheeting used to cover the muddy ground of the open field. The water level was soon over our legs as we sat cross-legged, having darshan of the Master.

The satsang continued – around thirty minutes passed and the cold crept into our bones as we sat, damp now to our waists. Suddenly a tiny girl, four or five years old, in filthy clothes, her eyes wide with terror, splashed towards us making little shrieking noises. A satsangi in front of me, Mike, reached over and lifted her up out of the water, holding her above it. Sitting just behind them, I could see her as he held this little bundle of bones out of the deluge. And I could see how she clung to him and how the terror started to leave her eyes. Perhaps she had been parted from her family in the throng; or perhaps she was an orphan, a street child scraping a bare living through begging and stealing. Perhaps she saw the crowds flowing towards the huge shamiana structure and she was drawn along, like a twig in a fast flowing river, towards the satsang. The rains came suddenly and in her terror she ran into the tent, panicked by the water now up to her knees, until she was lifted out by a gentle man.

I will never know how the story ended for that lost child, but believe that sevadars would have ensured that she was either re-united with her parents or placed with those who would care for her. The image of her rescue remains with me as an enduring impression of the day, somehow symbolising our own spiritual rescue (through satsang) from the world that would otherwise engulf us as surely as the water did.

In Moga’s satsang field, wet and bedraggled foreigners finally shuffled towards the buses, and found very welcome and reviving hot tea and sandwiches waiting. Despite being so cold, they were happy as they clambered into the buses for the return trip to the Dera. And then suddenly Baba Ji appeared. Even though the satsang audience was of many thousands, and he had so much to arrange – meeting the local sevadars and reassuring many Moga citizens who lined up to see him – he still made time to check on his cold, soaked guests. The Guest House people had all boarded, so Baba Ji approached each bus in turn, checking if everyone was well after the shock of the rain. This was my third lasting image – our Father making sure his children were safe and bringing us all face to face with the very source of love in action.

Turning Point

A newborn does not exercise a choice

but, helpless, leans towards its mother’s voice,

the one clear sound above a world of noise.

Like this O God,

I need you.A traveller stranded on a foreign shore,

longing for lands no longing can restore,

feels longing’s pain but may not know of more.

Like this O God,

I crave you.But when, as man, you come to lead the dance

and, turning, when we catch your gracious glance,

and though untrained, we follow you entranced –

O God, it’s then

I love you.

Original poem by a satsangi

Benefits of Satsang

Let us remind ourselves how lucky we are to be able to attend satsang. No matter when or where followers of the spiritual path gather for satsang, it is an important opportunity to make the most of a number of benefits. At satsang we can and should leave the world outside the door. It is a haven for us in which we all face in the same direction – away from the world outside and towards the Masters and their teachings. It is a refuge, available every week, and we come together to listen, to learn and to help create and then absorb an atmosphere of peace and love which we can then take away with us.

We are like nomads, travelling through an alien land but not here to stay. When we make camp in this world, it is only for the twinkling of an eye; then we will be away again and nothing will show for us having been here. So we should try to live lightly in this spiritual desert and not attempt to make it our permanent home. We can travel together with each other, the Master beside us, confident that we are now in good company. Here are a few pointers to the purpose of satsang:

Satsang helps us remember that this is not our true home. Though we recognize that the creation operates within the will of the Creator, this is not now where we wish to stay. It is an alien land for the soul that is starting to reassert itself after many aeons and millions of lives in servitude to the mind. The soul’s longing to leave this spiritually barren place will be establishing itself in the conscious mind of true seekers.

It is to remind us that we have a unique opportunity in having a human birth. In this form only can we make direct contact with the Creator, through a living Master, and journey all the way home.

It helps us to examine the various aspects of the path and to increase our understanding of the importance and significance of the spiritual teachings of the Masters. It is an opportunity to satisfy the intellect – which is a prerequisite to travelling the path.

Satsang creates and develops love and harmony among the sangat, encouraging us to remember that we are all members of the same flock, with the same Master who loves and cares for each one of us equally – no favourites, no hierarchy.

It sends us away with a revitalized desire to travel the path and attend to our meditation with renewed zeal.

Satsang puts ‘a fence around the crop’, as Maharaj Charan Singh used to say. Satsang is a form of protection for the efforts we have made. It nurtures the fragile shoots that we have started to grow through our meditation practice.

It is only through the understanding encouraged by satsang and our continual efforts to comply with the teachings, that our spiritual foundation will be made strong. The Masters teach that the time spent satisfying our intellect and investigating the path is not time wasted.

Baba Ji has made it clear that he is not here just to answer all our questions but to make us think! Once we are on the path, he wants us to go within and see and understand for ourselves, so that our faith is not founded solely on intellectual belief or conjecture but upon personal experience and knowledge. It is within ourselves that all questions are answered, that all hypotheses and conjecture translate into known fact. We cannot progress on the path without a good foundation in place. We all know what happens to a structure if the foundations are inadequate. Sooner or later it will fail.

There is a constant need for us to remind ourselves that the physical world pulls us downward and outward, whereas we must reorientate ourselves to go inward and upward. We are trying to swim against a merciless tide and our efforts can be likened to those of a snail crawling up the face of a waterfall. Like the snail we must keep close to the rock face, and inch our way up. If we lose concentration and look around, we are dashed to the bottom by the torrent of creation and must start again. The Master is like the rock face, and we should huddle close and take no risks. Every move we make can exacerbate our predicament and create more of the very karma that we are so painstakingly trying to remove.

So satsang reminds us of our goal and encourages us to strive to achieve it. We should make every effort to attend satsang regularly to enjoy all of its benefits.

An Unchanging Happiness

Moods change us. This ‘I’ changes with the tides of mood. The word ‘emotion’ is from the Latin for ‘out’ and ‘move’. How we emote or feel about some event depends on our perception of the event, apparently without our rationality. You get sacked from your job, for instance, and you feel miserable, rejected and powerless. You get a pay rise and you feel elated, proud and vindicated. But our response isn’t entirely out of our hands: it depends upon how we go on to interpret our circumstances. Getting sacked need not be a life-threatening event; the pay rise might be far less than you feel you are worth.

We think we can’t control the scripts of the soap operas of our lives, or how we perceive them, and that the tone of the drama dictates how we feel. Our happiness seems therefore to depend on the vagaries of fate, on the weather of life. Depression descends upon us when we take what happens as ‘bad’, as confirmation of our helplessness. But it is we who make the interpretation. The event itself is neutral and has no feeling.

Sure, I can try to change how I see things, but that’s not so simple, and you can’t do it directly, you can’t sit there and decide that being sacked isn’t a disaster. It can only come from developing a different view of who and what you are.

Most of the energy that humans put out, day after week after month, is in the attempt to change circumstance: to become rich, loved, esteemed, powerful, a better person, or someone who changes the world. I say to myself that the story I find myself in is not going in the direction I want it to: I will only be happy when I have achieved this, that and the other, when my circumstances are to my liking. Whether we are motivated by selfish or unselfish ideals, we are still in the process of trying to become what we would like to be, the process of getting our reality right.

All human beings are looking for a happiness that is not changed by physical or mental circumstance. But everything changes – everything starts, is sustained for a while, and then decays. Everything from ideas to human beings, from unhappiness to happiness, from universes to drops of water has a limited life span.

Truths and facts are no more reliable. They change: what was true in one era is stupidity in the next. It was once self-evident that the world was flat – everybody knew it to be the case. It was once lunacy to imagine that man could fly, let alone go to the moon. The nature of our universe is change, and yet our happiness depends on some things staying the same, and it is this investment in the possibility that some things are unchanging, and therefore dependable, that leads to our misery. Even our families come and go, quarrel and love, are born and die. Money is made and lost, pined for and worried over. Possessions are coveted, fawned over and stolen, and none of these tokens bring the unchanging happiness we long for.

But there is an unchanging happiness, an unassailable fortress of contentment that we can have access to, whatever the weather. It is ours already. We can find it inside, within ourselves.

For a happiness to be unchanging it must somehow be outside space and time, beyond change. This would seem to mean that it is therefore ‘somewhere else’, whereas the opposite is true. The prize of unchanging happiness is more here than we are. Or, rather, it is here and now, while we, mostly, are not. We are not here, now, because some or all of our attention is elsewhere. Attention goes to what we are concerned about or attached to. Attention is the means of our attachment – it is the application of consciousness.

But what is consciousness? It’s one of those words that we all use, and yet haven’t a clue as to what it actually is. What matters here is to understand that our consciousness is us. We are unconscious to the degree that we are not present. The more my attention is riveted to my attachments, the more unconscious am I. Were I able to gather all my consciousness, my attention, together in one spot, I would truly exist, I would be superconscious. As long as my attention is drained by focusing on my multifarious thoughts, I cannot be conscious, I cannot know myself. But consciousness can be directed – mystics are gatherers of consciousness.

All my thoughts are, one way or another, in and of time and space. But my consciousness is not. It is my window on transcendence. When I withdraw all my attention from my time-bound thoughts, my consciousness can know itself. As long as it is stuck on, and involved with, those objects (people, ideas, lusts, longings, fears, fantasies) it can only be occupied with trying to understand those objects and how they can be best manipulated to make me happy. When it is free from that attempt, it can know itself. It can know unchanging happiness.

Consciousness is a life and death issue: it is the difference between the two. Thus true living is a life of conscious connectivity – an unstinting and unchanging happiness: it is Shabd.

Undoing the Knot

Mind is an instrument originating from the second spiritual region known as Trikuti. Here it was joined together with soul or atman which descended from its original home in Sach Khand. Mind is assigned the role of assisting soul to engage with the physical creation. Over the ages mind has taken control of soul and, having usurped it’s power, now leads soul away from its true home with the Lord.

Mind is held in thrall to the five senses of touch, taste, smell, sight and sound. Mind works by association and having associated with the senses of the body, the mind gives so-called reality to the information they supply. Despite the illusory nature of this creation, it is mind that gives credence to the idea that the physical creation is our true home – that the pursuit of security and comfort in the form of material wealth and status is somehow a reality. Whatever mind wishes to do, and wherever mind wishes to go, soul has no choice but to follow.

Actually, mind draws its power from soul like the moon draws light from the sun, without which the moon would remain in darkness. Without the power of the soul, the mind as an instrument would become powerless. Mind and soul are therefore interdependent in this creation.

The living Master who accepts us as disciples teaches us how to overcome the mind by undoing the gargantuan knot that keeps soul and mind tied together. The true Master provides the disciple with the remedy of repetition of the five holy names which are charged with the Master’s power. The repetition of these five holy names is known as simran.

These powerful names are given to the disciple at the time of initiation and are to be repeated constantly throughout the day when we are mentally free. Then, at the time of meditation, simran is to be done for a minimum period of two hours followed by thirty minutes of bhajan – the practice of listening to the sound current or Shabd, also referred to as the voice of God.

When simran is done with love and devotion, the effect is to draw mind away from the pull and attraction of the senses so that the attention no longer disperses through the nine apertures of the body. This important practice of simran is the method by which soul can escape from the prison of mind and body and collect at the eye centre, or third eye. At the time of initiation, the Master has placed his own Radiant Form, the Shabd form, within the disciple to await the arrival of mind and soul at the eye centre.

Our spiritual journey can only begin from the eye centre, the headquarters of mind and soul; and the eye centre can only be entered by the grace of the Master, through one-pointed concentration at this location. Once the disciple gains entrance to the eye centre, the Master continually works with the disciple, shaping and moulding him or her.

Meditation is primarily an exercise in handing oneself over to the Shabd. It is an exercise in self-surrender, which enables the Master to draw the mind and soul inwards and upwards to the point at which the mind will merge into its own source (Trikuti), leaving the soul free and unencumbered at last. The level of surrender that needs to be attained is such that the mind of the disciple is no longer dominant but submits to the Master. This is where simran of the five names is essential. Repetition of the five names must be done regularly and constantly so that it becomes a ceaseless prayer. This will enable a person to develop a full inner life, led by the soul. Always having the Master at the forefront of all one’s activities prevents the mind from dominating the soul. It helps the Master to awaken the disciple’s love that lies sleeping deep within.

Simran of the five holy names helps bring about full concentration and diverts the attention away from the sense outlets (the nine doors) of the body. The attention or soul consciousness then rises automatically within, penetrates the veil of ignorance, and gains entrance to the third eye. That is how to become God-centered. One who is fully concentrated through repetition of the five holy names will eventually enjoy spiritual bliss, sometimes described as the amrit or elixir which is kept within every human being.

Baba Ji says that true prashad can only be found within. The outer prashad that we are given by the Master is given to us as a reminder of the master’s love and his teachings. Maharaj Charan Singh says in Quest for Light that simran is a great power and it is this that will take us to the Radiant Form of the Master, from where the true sound will start and the inner spiritual journey will begin.

Living with a Serious Illness

We human beings are subject to the pairs of opposites that belong to this physical world – conditions such as health or sickness, wealth or poverty and happiness or sadness, all of which may affect us at any time of life. When we, or those we care for, become ill, the situation may even be critical or life threatening. Yet however helpless we feel, it is important to remember that a choice is always open to us .We can choose either to be a victim or we can choose to be a willing participant in the flux of life, accepting our destiny with courage.

When we play the part of a victim we probably cry, “Why me? How can I have such bad luck as to end up with this awful disease?” But if we choose to remain in control, it’s time to be positive. Instead of wrapping ourselves in self-pity, we can look objectively at the situation. If we turn around we will see that we are not alone – many people suffer in life, some in most dreadful ways. Why should we be exempt from the laws of life? Maharaj Charan Singh puts our suffering into perspective. He writes in Divine Light:

All pleasure, pain, poverty and disease are parts of our life due to our past actions. Disease, poverty and pain are for our own good. They turn our face to the Lord and create humility, meekness and devotion in us. They are essential parts of the economy of creation and are as necessary as health, wealth and pleasure.

If we align our thinking with this perspective rather than remaining in our own isolated bubble, the acceptance it brings will be a source of strength and comfort to us. We should take what steps we can to get medical treatment and then be patient. The meekness, humility and devotion that Hazur mentions are spiritual attributes that we must develop at some time in our quest for God-realization. Through the medium of the serious illness – previously seen as a blight – we can learn to practice these attributes. For instance, finding that we are dependent on doctors, nurses and friends may be a bitter pill, but if it teaches us to let go and be grateful, we have received a wonderful blessing. And if in our hour of need we turn trustingly to the Lord, the illness is his grace indeed.

Applying clear thinking is a start and we should then continue to reach out for a positive perspective, using the tools we have been given at the time of initiation. For a satsangi, the best way to keep humble and positive is to do simran at the time of meditation and simran all the day when the mind is free. This spiritual repetition, with focus, draws us into the field of the divine energy which is actually always within us; mere intellectual assertion is never enough, but when we align ourselves with our Master through simran, negativity is dissolved.

We similarly need this support if we have a friend or family member who is suffering. Telling the person we are caring for to cheer up, they are just going through their karma, is not necessarily helpful. Do we know it’s all karma or are we just repeating a concept? But by regularly doing our meditation and keeping the Master in mind, understanding and empathy will be increased; we will automatically be led to helpful actions which bring genuine cheer.

Though we are told that this plane of existence is all illusion, our suffering and that of dear ones naturally feels real enough to us. To get over this we must dig deep, have faith in the teachings and do our spiritual practice. This is the route which gives us the power to bear what we must and to help ourselves and others.

Why Question?

In life we are continually preoccupied with asking questions. We want to know when and how things will happen, building up a picture of the world around us, hoping for reassurance and a sense of control. We also question the objects and events of the universe beyond us. For instance, science is questioning how this world came into existence and has postulated various theories.

Physicists today believe that they have an ultimate theory which will explain everything – they call it the string theory or the theory of everything. But they also deduce that more than 90 percent of this universe is still not understood. Dark matter and dark energy are out there, but what exactly they are nobody knows. Science changes over the centuries and even over the decades. The science of ancient Greece differs from the science of the Middle Ages, which is different again from that of the modern era. As the hypotheses change, so do the possible answers. In two hundred years’ time, there will still be unanswered questions!

Why do we need to keep on asking? Isn’t it just to strengthen our small and lonely selves? And whether our questions are to do with our personal lives (perhaps trying to make sense of the things we are attached to) or whether they concern the wider world, aren’t we looking in the wrong direction for answers? The fact is, as Maharaj Charan Singh very beautifully told us, this world is both imperfectly perfect and perfectly imperfect. Whichever way you look at it, it comes to the same thing: there are no final answers to individual questions, only one answer, which is reached by transcending our human state. It’s rather as if we were in a factory in which there are hundreds of machines; the noise is deafening so we are seeking to control the environment by turning off each machine, one by one. If we were to find the main power button, we could stop the whole factory at once, and enjoy blissful silence. Sant Charandas advises:

Things of this world come and go

O friend, grieve not for these,

This world is superficial,

O friend, realize the Lord.

We have taken a very long journey in the course of our evolution as humans; it has taken us through many species over many aeons and we are still imprisoned by our small selves, the remains of animal behaviour still clinging to us. No answers in the physical world will help us one bit, but if we surrender the ego, then, like finding the central button that controls the factory, all questions will come to an end and we will come face to face with the Truth.

True Masters come to enlighten us regarding the truth. Truth is not dependent on anything external and is not subject to time and change. The greatest obstacle in our understanding is that we believe we depend on this transient visible world rather than on that which cannot be seen. This entire creation owes its existence to an unseen Creator and his unseen Shabd. Because of our long separation from him over innumerable lifetimes, we have forgotten this fact, becoming dependent only on what we can see and experience in the physical domain. This explains the deep attachment we feel for friends, relatives, country and culture. It’s difficult for us to accept that there is another reality. To find that reality, that Truth, is the purpose of human life. Sant Charandas states in another poem:

O Saints, this carnival will end in a short while;

We will depart after watching this show.

Never again will you meet those

Who have gathered here together.

Many travellers from different directions

Cross the river in a boat – they meet

Only to go their separate ways a few moments later.In this give and take, each action has its consequence,

So do your real work

Develop love for the Lord,

Who is your real benefactor.

Just imagine when you die, wanting to take with you all the things you are attached to (it could be books, house, family, furniture, fame) and all these things have to be pushed through the tiny sesame seed opening of the third eye. That’s a painful operation! It’s because of our attachments that dying is such a painful event, as Charandas tells us:

O friend! You have never understood the extent

Of the Lord’s love.

He created you for repeating his simran,

But you decided to do otherwise.

Once a lady in a Q&A session with the Master talked about her young son who had recently died. She loved him so much and was extremely sad, no doubt questioning why someone so young should die. The Master asked her whether she could imagine how much love the Lord had for her? The Lord had had a connection with her for so much more time than she had with her son. She had had a bond with the Lord for aeons. She had built that other love in just a few years, whereas the Lord has loved us for eternity.

This world has never been a place of satisfaction, and it never will be. That’s the only thing we can learn from history! The Masters explain that we must go to our real home, the home of the Lord. The Saints explain that through meditation we are able to directly experience the difference between material happiness and spiritual bliss. So instead of constantly questioning and seeking for outside answers, we must quieten our mind through meditation and go inside ourselves to see the reality

Intellect cannot lead us anywhere, but the satisfaction of the intellect will give you faith and practice: if you try to brush aside your intellect and try to attend to meditation, you will never succeed. Intellect will always jump in the way. But if you satisfy your intellect with reasoning, then faith will come and practice will come, which will then take you to your destination….

If you want to follow the path without satisfying your mind, then questions and doubts arise, and whenever you sit in meditation all those things will come before you. They won’t let you sit in meditation at all.

Maharaj Charan Singh, Die to Live

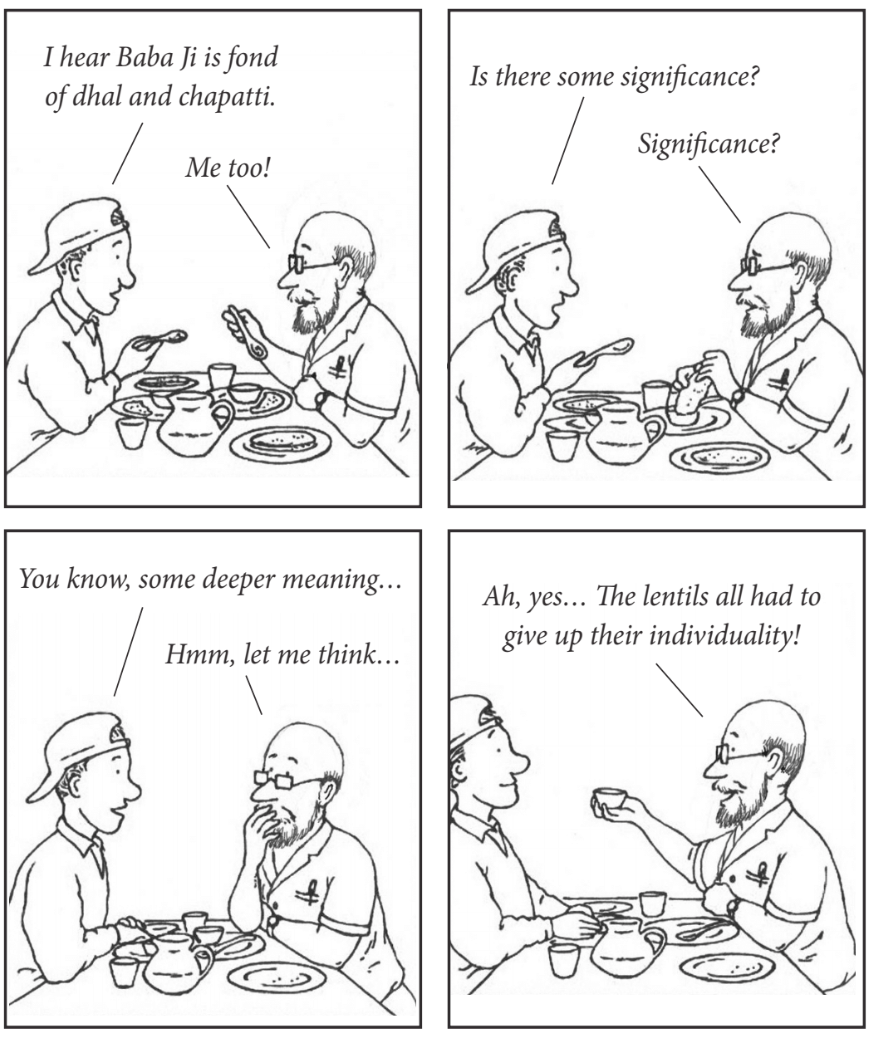

Food for Thought

Tim’s Lunchtime Chat

Tim is a newcomer on the path who enjoys the interaction with older satsangis. His friend is a veteran… with a naughty sense of humour.

Those Who Bend Are Great

“Those who bend are great” is a wise Chinese proverb which, if applied to our own lives, would bring balance and harmony. We’re all in need of some tranquility and peace of mind to help us focus on our Master, and there is deep meaning in these words.

Bending involves being flexible, accommodating, and cooperative. This attitude is linked to humility. Through practising humility – even though our mind resists – it becomes part of our lives and then genuine humility develops. The Master loves humility in his disciples. In Philosophy of the Masters, Maharaj Sawan Singh tells us:

One who desires communion with the Almighty Father should first of all wash the dirt from his mind with the water of love.

The way to wash away our dirt and ego is by attending to meditation with devotion and commitment. Then we may find that we are given learning situations that help us to see our mistakes; we will learn to let go and be flexible rather than turning small things into big issues. The Master encourages us to do physical seva at the satsang centres, and be helpful in our families and communities. Serving, giving, and adjusting help us to overcome our selfish habits.

The ego cleverly uses the idea that we should not be a doormat. Our selfish tendencies force us to take care of our own needs first. We might put up unnecessary barriers to protect ourselves. We can become rigid, closed, possessive, and proud of our opinions. We could even start to dislike others who do not follow our way of thinking or acting. This prevents us from being happy and blocks our spiritual progress.

If we find difficulties in seva, we soon realize that it is because we want things our own way – we want to receive instead of to give, we expect things to comfortably fall in line with our own concepts and beliefs, thinking we are right and others are wrong. When we refuse to understand, bend and harmonize, we make ourselves unhappy and stressed. The answer is to try to realize these situations as the Master’s gift. When our ideas, desires or traditional ways of thinking are upset by others, he is using the other person to highlight our rigidity. He is giving us the opportunity to chip away at our ego. He is teaching us humility.

This does not mean that we should not calmly stand up for what is morally right. It certainly does not mean compromising on the Sant Mat principles, and we should have no fear of public opinion as far as this is concerned. Sticking to the principles ensures that we keep clean, pure and strong, so we should never bend these rules. The Masters know that we all need a structure to protect us from the mind and senses that constantly try to take us away from the inner path. To live each day on the spiritual path, we always ensure that we keep the four vows – adherence to the vegetarian diet, avoidance of alcohol and mind-affecting drugs, living a moral life and carrying out daily meditation. If we stick to these principles then we can safely bend to all else.

Once we see that the Lord is the doer, the planner and the architect, we can trust that whatever others do to us, good or bad, right or wrong, pleasant or painful, is coming from him. He will support us when we have the sincere intention to follow the teachings. If we have faith and trust in him, the boon of flexibility and contentment will develop within us. “A heart full of love is contented and sweet”, says Maharaj Sawan Singh.

Sant Mat is so simple. Stick to the four principles and adjust to our life circumstances. Focus on the Master, trust him – all else is illusion. We can do this when we put our meditation first. When we meditate we will become relaxed and happy and that will enable us to leave it all to the one who loves us.

Once a dervish came before Sikandar (Alexander the Great), with the bowl of a beggar and asked him if he could fill it. Sikandar looked at him and thought, “What is he asking of an emperor like me? To fill that little bowl?”

But the bowl was a magic bowl. Hundreds and thousands and millions were poured into it but it would not fill. It always remained half empty, it’s mouth wide open. Sikandar asked, “Dervish, tell me if you are not a magician? You have brought a bowl of magic! It has swallowed my whole treasure and is empty still.”

The dervish answered, “Sikandar, if the whole world’s treasure was put into it, it would still remain empty. Do you know what this bowl is? It is the want of man.”

Be it love, be it wealth, be it attention, be it service, be it comfort, be it happiness, be it pleasure, be it rank, position, power, honour or possessions in life, the more man can receive, the more he wants. He is never content, he will be never content. The richer man becomes, the poorer he becomes, for the bowl that he has brought with him, the bowl of want, can never be filled.

Inayat Khan, as quoted in A Treasury of Mystic Terms Part 2, Vol. 7

Under the Master’s Protection

We would be very pleased and surprised to know the depth of our Master’s concern for us, as shown by this very interesting extract from Treasure Beyond Measure. It is a friendly exchange between Maharaj Charan Singh and a satsangi couple:

Whilst visiting our home on one occasion, Maharaj Ji advised my wife, “Behenji, please attend to your simran regularly for the next thirty days.

But she replied jokingly, “You do it for me” because we had known Maharaj Ji for ten years before he became the Master, and he was always like a family member to us, afterwards keeping up the same relationship.

Again, whilst sitting in the car when he was about to leave, he emphatically told my wife that she must attend to her simran. But she did not take the advice seriously and never did it.

Some time later, we had to leave our home in order to attend a marriage at Simla. After four days had passed, we received a trunk call from a neighbour, stating that there had been a theft in our home, committed by our servant. We returned that evening and found that all our valuables had been stolen. We informed the police and then wrote a letter to Maharaj Ji. But before he could receive it, a letter arrived from him in which he mentioned that he knew what had happened.

After a few days he came to visit us and said to my wife, “I had asked you to attend to your simran, but you did not do it. Now, just forget whatever your servant has taken from you and be grateful to the Lord for what is left behind, as this is sufficient for your needs.”

I said, “Maharaj Ji, she was expecting sympathy from you.” Maharaj Ji replied, “I am sympathizing with her, as so much has been left!” Everyone laughed and by his grace, we took the whole incident lightly.

The couple was to go through the distressing experience of finding their home ransacked and that a trusted servant had abused their trust. The Master, knowing what was to happen, tried to save his friend’s wife from pain and agitation. He asked her to focus on her simran.

If we ponder on this little story for a minute, it graphically illustrates to us that when a Master suggests something to us, we should take it very, very seriously indeed and act upon it. Why is it that we take so little notice of the fact that he pleads with us constantly to actually apply ourselves to our simran and bhajan as a matter of high priority? There is nothing in this life more important for us if we are to achieve our goal, yet our minds find every excuse possible to wriggle out of it. If we thought that we were going to die within the next few days or weeks, wouldn’t we reorganize our lives to make sure that it became our first priority? Suddenly none of our other commitments would feel nearly so important.

The Masters come to this world to give us a clear, simple and beautiful message which transforms the lives of those who – by his grace – are able to hear it. They explain to us that all that we see before us is a play which is fleeting and constantly subject to change; it will come to an end one day. Nonetheless, there is a seed within all of us which is waiting to germinate when the time is right for us to begin the journey back to our source. That seed may have been buried in the mud of our karmas for aeons, but when the moment is right it will start to grow. Then we will reflect on what life is all about and why we are here.

The utter joy of it is that the Masters’ message is incredibly simple and the practice we are asked to carry out is one that even a child can do. The true Master takes a human form but is from the very highest level of creation, and he knows and understands, from his own experience, how the creation works.

When we come under the living Master’s influence, we are encouraged to change our lifestyle. What was negative and self-destructive becomes life and spirit enhancing through following four simple principles – lacto-vegetarianism; avoidance of alcohol, recreational drugs and tobacco; the development of a disciplined moral life; and, when initiated, the resolution to work up to two and a half hours of meditation a day. These principles transform our lives and prepare us for the inner journey home to Sach Khand.

There is one piece of advice which all Masters give, and that is to do our meditation regularly, with love and devotion. If we can put this first in our lives, he will take care of the rest. So many of us use the excuse that we are just no good at it, that we cannot concentrate for even two minutes at a time; but he assures us that turning up and sitting there regularly – whether we focus or not – still counts for something.

The important thing is that we set aside that time and keep on trying. If we think about the incredible way in which he showers his love and looks after us, can we not at least put in the effort to sit and say, ‘thank you’ every day by doing our simran? We have our five holy names to repeat so that we can live in remembrance of him day and night. The Lord has imbued these five simple words with immense power. They act as our safeguard, our protection, and very importantly, our means of inner communication with our Master. We should never underestimate their significance.

Maharaj Jagat Singh reminds us in A Spiritual Bouquet:

Our love for the Lord requires constant feeding. Like fire, it is apt to die out without fuel. Bhajan and simran is the fuel that sustains this fire. So never miss bhajan for a single day. One day’s negligence in bhajan retards the progress of the journey by one month.

Our prayers and pleadings are quite useless, unless these are supported by all the effort on our part to push the door open. The Master knows that we are only feigning thirst and desire for Nam. Our prayers are not sincere and true. Our mind is still steeped in cravings for the world and its objects. It is submerged in lust and greed. It is running after name and fame. It constantly lives in vanity and pride. Remember that a Master cannot be deceived or cheated. Unless the yearning to meet him is intense and true, he remains silent and inattentive.

Don’t Expect

Baba Ji explains that pain comes from expectation. He points out that if we expect something from another as a reward for what we have done, we will definitely be disappointed.

Consider first the karmic arena in which the Lord has placed us: Whether we are married or single, healthy or sick, employed or not, part of a family or alone, don’t most of our problems stem from expecting something from another party?

Second, any dissatisfaction we feel about this path usually comes from our expectation, built up by an intellectual concept of how we think we should spiritually progress, based upon the effort we feel we have made.

In most cases, isn’t our expectation rooted in pride? We think first about what we should be getting rather than considering what we should be giving.

Baba Ji further elaborates that when we stop expecting things from everyone else and focus instead on what we should be doing for the reality within us – our soul – we experience contentment and peace of mind. It is difficult to do this at our level, entangled in the world and slaves to the mind as we are. But as all the Masters reiterate, when our first priority is turning inward to the Lord, nothing is impossible.

When initiated, we should do our simran and bhajan without expectation. The Lord and the Master, omnipotent and omniscient, will make us conscious of the Holy Name, the Shabd which will take us homewards. Only beyond the mind regions, will our pride be overcome.

Book Review

Mindfulness: A Practical Guide to Awakening

By Joseph Goldstein

Publisher: Boulder, Colorado: Sounds True, Inc., 2013

ISBN: 978-1-62203-063-7

‘Mindfulness’ is a popular concept among many spiritual seekers today, but it is often misunderstood or interpreted in a superficial way. In Mindfulness: A Practical Guide to Awakening, Joseph Goldstein brings the concept and practice of mindfulness back to its Buddhist roots by describing its systematic instruction in the Satipatthana Sutta.

The Satipatthana Sutta is the Buddha’s Discourse on the Four Foundations of Mindfulness, and one of the core texts of classical Theravada Buddhism, written in the Pali language. Goldstein says, “In the Satipatthana Sutta … there is a broad range of instructions for understanding the mind-body process and different methodologies for freeing the mind from the causes of suffering.” Bhikkhu Bodhi, an American Theravada Buddhist monk, states that this sutta (sutra in Sanskrit) “is generally regarded as the canonical Buddhist text with the fullest instructions on the system of meditation unique to the Buddha’s own dispensation.” Goldstein quotes copiously from the sutta, and includes at the end of the book a full translation by Analayo, a German Buddhist monk who has studied the sutta extensively.

The sutta begins with what Goldstein calls an “amazingly bold and unambiguous statement”: “This is the direct path for purification of beings, for the surmounting of sorrow and lamentation, for the disappearance of pain and grief, for the attainment of the true way, for the realization of nibbana (in Sanskrit, nirvana) – namely the four foundations of mindfulness.” The term ‘mindfulness’ is a translation of the Pali word sati which means ‘to remember.’ Goldstein states that “the most common understanding” of sati is “present-moment awareness, presence of mind, wakefulness,” or “a quality of receptivity that allows intuitive wisdom to arise.” Sati also means ‘to see clearly’. According to Goldstein, mindfulness is one of the key practices to achieve freedom. “Without mindfulness, we simply act out all the various patterns and habits of our conditioning.” Contrary to popular belief, our aim should be “not to follow the heart but to train the heart.” We have a mixture of motivations, and not everything in our heart is wise. “The great power of mindful discernment allows us to abandon what is unwholesome and to cultivate the good. This discernment is of inestimable value for our happiness and well-being.”

The chapters of Mindfulness: A Practical Guide to Awakening follow the format of the sutta, discussing in turn each of the four foundations of mindfulness – mindfulness of body, of feelings, of mind, and of dhammas. Mindfulness of the body includes mindfulness of breathing, of meditation postures, of physical characteristics, and of the intentions and motivations behind our physical actions. In the Buddha’s teachings, as Goldstein explains them, mindfulness of the body is the “simplest and most direct way for overcoming the onslaughts of Mara, the forces of ignorance and delusion in the mind.… In the midst of endless thought proliferation, of emotional storms, of energetic ups and downs, we can always come back to just this breath, just this step.”

Mindfulness of feelings means mindfulness of “that quality of pleasantness, unpleasantness, or neutrality that arises out of the contact with each moment’s experience.” Goldstein explains that mindfulness of feeling is one of the “master keys that unlocks the deepest patterns of our conditioning.” He points out that the Buddha elaborates on mindfulness of feelings “when he talks of two kinds of people: the uninstructed worldling and the instructed noble disciple. When the uninstructed worldling is contacted by a painful feeling, he/she feels aversion to it, feels sorrow and grief, and becomes distraught.” The uninstructed worldling reacts to life with conditioned, habituated tendencies, rather than exercising the “wisdom of non-reactivity” of the mindful disciple. Interestingly, the feelings of pleasantness, unpleasantness, and neutrality can be either worldly or unworldly. Pleasant unworldly feelings are generosity, compassion, concentration, insight, and awakening; unpleasant unworldly feelings – which lead to spiritual seeking – are awareness of suffering, loneliness, longing, and loss of self; and neutral unworldly feelings include equanimity and balance.

Mindfulness of mind refers to an awareness of wholesome and unwholesome states of mind. The three roots of unwholesome states of mind in Buddhism are greed, hatred, and delusion, and the three roots of wholesome states of mind are concentration, loving-kindness, and compassion. The Buddha says that understanding how the unwholesome states condition our minds enables us to discern whether our actions, thoughts, and attitudes are skilful or unskilful. That which is skilful leads to happiness and liberation, and that which is unskilful leads to suffering.

The instructions in the sutta help the practitioner to work with the unwholesome states in a productive way. “Instead of drowning in the defilements through identification with them, or judging them, or denying them, the Buddha reminds us to simply be mindful of them both when they are present and when they are not, remembering that they are visitors.” But we can also be too focused on the unwholesome states of mind. It is important, Goldstein says, to be equally mindful of the wholesome states of mind:

For some reason, we are more likely to dwell on the difficulties and we often overlook the presence of the wholesome states of mind. This has a major effect on how we view ourselves. In this section of the Satipatthana Sutta the Buddha is giving equal importance to being mindful of each.

Mindfulness of the dhammas is the fourth and final foundation of mindfulness and is often translated as mindfulness of mental objects. The Pali word dhamma (in Sanskrit, dharma) has a wide range of meanings, including “truth,” “the law,” or “the teachings of the Buddha.” Indeed, in the spirit of the latter meaning, the Buddha included in this part of the sutta a comprehensive list of the basic organizing principles of his teachings: the Five Hindrances, the Five Aggregates of Clinging, the Six Sense Spheres, the Seven Factors of Awakening, the Four Noble Truths, and the Noble Eightfold Path. “Mindfulness of the dhammas” helps us to transform the doctrines that we have understood as theory into knowledge that we perceive and know through our own experience. “It is this transmutation of doctrine into direct perception that brings the teachings alive for us. Instead of a philosophical analysis or discussion, the Buddha is showing us how to investigate these truths, these dhammas, for ourselves.”

Mindfulness, in addition to being a concept and mental faculty to be cultivated in all the four foundations, is also specified as one of the Seven Factors of Awakening which incline the mind toward nibbana or freedom. The seven factors are mindfulness, discrimination, energy, rapture, calm, concentration, and equanimity. Among these, mindfulness has a unique role, as it serves to balance the other six factors.

Goldstein stresses that the key to mindfulness is practice. “Whatever we repeatedly practice begins to arise more and more spontaneously.… From the repeated effort to be mindful in the moment, there comes a time when the flow of mindfulness happens effortlessly for longer periods of time.” Bhikkhu Bodhi goes further:

Liberation … is bound to blossom forth when there is steady and persistent practice. The only requisites for reaching the final goal are two: to start and to continue. If these requirements are met, there is no doubt the goal will be attained.

Joseph Goldstein is one of the foremost American teachers in the Theravada Buddhist tradition, also known as vipassana meditation practice. He spent seven years studying Buddhism in India with a number of eminent teachers from India, Burma and Tibet. When he returned to the U.S. in the 1960s, as one of the growing number of Americans interested in Eastern spiritual beliefs, he began teaching Buddhist meditation practice at Naropa Institute (now Naropa University) in Boulder, Colorado. Goldstein co-founded the Insight Meditation Society and the Forest Refuge in Barre, Massachusetts. He has written a number of influential books about Buddhism including Insight Meditation: The Practice of Freedom, and One Dharma, which integrates the three main traditions of Buddhism – Theravada, Tibetan and Zen.

Book reviews express the opinions of the reviewers and not of the publisher.